Elizabeth I 1558-1603

Elizabeth (pictured - from the portrait by George Gower) was born to Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn in 1533, and became queen in November 1558 on the death of her half sister Mary. Her reign was a period of extraordinary expansion: Elizabethan England 'took the world by surprise' (Leach 1915:332) - in navigation, commerce, colonisation, poetry, drama, philosophy and science. Much of this was due to 'the immense extension of lay initiative and effort' in every area of national life - 'not least in the sphere of education and the schools' (Leach 1915:332).

Elizabeth (pictured - from the portrait by George Gower) was born to Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn in 1533, and became queen in November 1558 on the death of her half sister Mary. Her reign was a period of extraordinary expansion: Elizabethan England 'took the world by surprise' (Leach 1915:332) - in navigation, commerce, colonisation, poetry, drama, philosophy and science. Much of this was due to 'the immense extension of lay initiative and effort' in every area of national life - 'not least in the sphere of education and the schools' (Leach 1915:332).

In assessing the development of education in the Elizabethan age, Joan Simon identifies three key issues:

First, the extent to which control was exercised over the school system ... and the direction in which developments were influenced. Second, 'the institution of the gentleman', in the contemporary phrase, what this stood for in theory and practice. Third, the wider demand for education fostered by the protestant ethic and the development of vernacular culture; the ways in which this developed and was met (Simon 1966:298).

Religious background

Elizabeth inherited a country plagued by confusion and division over religion. Henry VIII had broken with Rome but had never been an enthusiast for Protestantism. Under his son, Edward VI, the process of creating a Protestant nation had begun, but Edward had died young and Mary had attempted - unsuccessfully - to reimpose Catholicism.

Advised largely by Sir William Cecil, her Secretary of State, and Sir Nicholas Bacon, the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, Elizabeth now set about bringing the confusion to an end. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement of 1559 consisted of two Acts of Parliament: the 1558 Act of Supremacy, which re-established the Church of England as independent of Rome; and the 1559 Act of Uniformity, which required attendance at the Sunday services of the Church of England and prescribed a new version of the Book of Common Prayer. Elizabeth and Cecil then drafted additions to the settlement, known as the Royal Injunctions. England was now officially a Protestant nation.

Religious issues were at the heart of both the Reformation and the Renaissance. As Joan Simon has argued:

it was not until the contradiction between faith and learning was 'resolved' by making a clear separation between reason and revelation - as Vives had been inclined to do and as Francis Bacon was to do for his generation - that scientific thinking in the modern sense of the term had room to develop; meanwhile scholarship in the sixteenth century was concerned rather with the clearing away of settled landmarks and the search for new viewpoints than with a clear advance on new lines (Simon 1966:358).

Puritanism

Puritanism was a key element in the religious conflicts of the Elizabethan period:

'puritanism' is a category as difficult to disentangle as 'humanism' at an earlier stage; it, too, extends to cover a whole set of attitudes, a way of thought and approach to learning, not merely advocacy of the Genevan form of church government. Though there were some who actively pursued this end, and in so doing raised important political issues, it is not helpful to conceive of puritans in general as a tiresome and noisy left wing of a settled Anglican church. Rather the theology of the Elizabethan church was predominantly Calvinist and in this sense puritanism was in the mainstream of development; those called puritans were the most thoroughgoing upholders of the Reformation (Simon 1966:292).

In the earlier years of Elizabeth's reign 'the nature and standard of education depended largely on the quality of the clergy' (Simon 1966:320). Here was a vicious circle: 'there was no real incentive to education so long as the church could not provide due rewards for the educated but there could be no real reform of the church until it incorporated more educated men' (Simon 1966:320). The suppression of Puritanism reduced the number of competent ministers. However, some of those banned from preaching often turned to teaching, 'thus adding anew to the number of puritan schoolmasters' (Simon 1966:320). In 1577 Bishop of Durham Richard Barnes urged all parsons, vicars and curates not licensed to preach, to

duly, painfully and freely teach the children of their several parishes and cures to read and write; and such as they shall by good and due trial find to be apt to learn, and of pregnant capacity, then they shall exhort their parents to set them to schools and learning of the good and liberal sciences (quoted in Simon 1966:321).

In 1576 Edmund Grindal, now Archbishop of Canterbury, began to promote 'prophesyings' (as he had done previously as Archbishop of York). These were monthly meetings of the clergy designed to raise the standard of education and preaching. Elizabeth, 'who saw no call for a learned clergy beyond one or two preachers for each county' (Simon 1966:322), did not approve.

In the 1580s some church congregations set up a system of presbyterian classes whose members were determined to put into practice their belief that education should be available to all. Thus the elders of the Dedham 'classis' set up a school so that every child would be taught to read, provided a house for the master, and used some of the church collections to pay the fees of poor children. The classis movement prompted the new Archbishop, John Whitgift, to take further measures against the Puritans.

The Puritans, once again linking the expansion of education with reform of the church, submitted proposals to the parliament of 1584 in support of a better educated ministry and a reduction in the power of the bishops. They wanted an end to plurality and non-residence in favour of providing adequate livings for parish clergy. Instead of maintaining singing men, cathedral endowments should be used to support preaching ministers, grammar schools and poor scholars at the universities - 'the kind of programme William Turner had advanced from Basle thirty years before' (Simon 1966:327). The proposals were not accepted.

Also in 1584, Sir Walter Mildmay founded Emmanuel College at Cambridge. Its purpose was to

'render as many as possible fit for the administration of the Divine Word and Sacrament ... that from this seed ground the English Church might have those that she can summon to instruct the people and undertake the office of pastors, which is a thing necessary above all others' (quoted in Simon 1966:328).

Emmanuel served as a model for Sidney Sussex College, founded by Frances, countess of Sussex, the aunt of Philip Sidney. Thus 'the two colleges established during Elizabeth's reign were ... founded at Cambridge under puritan auspices' (Simon 1966:329).

Towards the end of Elizabeth's reign, the Privy Council put pressure on Whitgift - who was a strong supporter of the queen - to modify his campaign against the Puritans. As a result, many suspended ministers were restored to their posts, and Whitgift focused his efforts on destroying the classis movement. He also drew up ambitious plans - similar to those of Edward's reign - for educating the clergy:

This policy, applied at a time when more scholars were coming up through school and university, bore fruit. By 1598 about half the clergy held a preacher's licence, many of these being graduates, while some of the rest had attended university for a time (Simon 1966:331).

But attempts to create a presbyterian system of church government failed and the Anglican church - 'now nearly half a century old, practically strengthened and gaining doctrinal support at last from Hooker's Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (1597) - began to appear almost established' (Simon 1966:331).

However, Calvinism had 'struck deep roots' (Simon 1966:331) at both Oxford and Cambridge:

At Cambridge the regular sermons given by William Perkins ... were one of the chief features of university life; and the treatises of this spokesman of the new puritanism, which would prevail in the coming years, made up nearly a quarter of the 200 works published by the university press between 1590 and 1618 (Simon 1966:331-2).

Despite the attempts to suppress it, Puritanism continued to flourish, leading ultimately to the English revolution and the abolition of the monarchy in 1649.

Catholicism

Despite the Elizabethan Religious Settlement of 1559, Catholicism continued to cause problems and further attempts were made to suppress it. An enlarged edition of the Book of Martyrs by John Foxe (c1516-1587), published in 1570, was soon found in parish churches and many households, and Alexander Nowell's new catechism was prescribed for general use: an English version, by Thomas Norton, a leading Puritan in parliament, was also published.

In the 1580s Jesuit missionaries, 'carefully educated abroad and single-mindedly devoted to their task of retrieving the English gentry for the catholic faith' (Simon 1966:324) began arriving in England. Many were kept in gentlemen's households under the guise of tutors. The Privy Council expressed concerns about the failure to protect schools from Jesuit influence.

The schools

While Edward VI's reign had been a period of educational advance, Elizabeth's was predominantly conservative: the aim now was to 'ensure unity in religion and consolidation of the social order' (Simon 1966:291).

The Reformation had diminished ecclesiastical control and 'a variety of schools had come into being in a haphazard way' (Simon 1966:291). Under Elizabeth, there were few grants in aid and fewer refoundations than in Edward's day, but immediate efforts were made 'to place schools on a sound footing after the disastrous interlude of Mary's reign' (Simon 1966:304). The schools were reorganised and adapted: many chapels became schoolhouses, and benefactions which would once have served to maintain Masses now went to extend the system of schools. At the same time, 'humanist theories merged with reforming ideas in the formulation of educational programmes' (Simon 1966:291).

Wealthy merchants continued to found schools and endow scholarships and fellowships at colleges. While the aim of these was often to improve the education of the clergy, they also proved beneficial for townsmen and rural yeomen - indeed all except the poor, whose numbers were growing. Elizabeth's reign also saw the rise of substantial yeoman farmers, especially in the midlands, and some of these founded schools in market towns and even in larger villages.

Across the country, many schools were established - petty schools for the children of the poor as well as grammar schools 'for the sons of the better off' (Lawson and Silver 1973:104). Where there was an endowment, trustees were given responsibility for 'appointing the master, administering the property and generally watching over the school's interests' (Lawson and Silver 1973:104). Some founders also issued statutes setting out the curriculum and rules for the conduct of the school.

Local schools were sometimes paid for by residents. At Willingham in Cambridgeshire, for example, 102 villagers gave a total of £102 7s 8d in 1593 to endow a school for their own children and for some poor children who were admitted free. 'Whatever the impulse, private philanthropy enormously enlarged the country's educational resources between about 1560 and 1640' (Lawson and Silver 1973:107).

In London, Westminster School was refounded by Elizabeth (1560), and a new Merchant Taylors' Company school was founded (1561) with Richard Mulcaster as its first master. Elsewhere, statesmen such as Sir Gilbert Gerrard and Sir Nicholas Bacon supported the establishment of schools in counties where they had influence, and other schools were set up with no particular sponsor named - such as those at Mansfield and Godmanchester in 1561 and Kingston-on-Thames in 1562. More schools were handed over to the boroughs: Reading, for example, gained control of its former monastic school in 1560.

Many towns were proud of their new schoolhouses, often provided mainly by public subscription. At Leicester, for example, the members of the town's governing body paid for a new school and recorded its completion in the hall book:

In this year, viz. the sixteenth year of the reign of our most dread sovereign lady Queen Elizabeth was the School house builded and finished. Item the same year was a new house erected and builded ... appointed for the head school master to dwell in (quoted in Simon 1966:315).

Girls were often taught alongside boys in the elementary schools, but Richard Mulcaster (in 1581) argued against coeducation in the grammar schools. In 1589 the statutes of Harrow specifically excluded girls from the school, which Rosemary O'Day suggests may indicate that there had been 'some debate about their possible admission' (O'Day 1982:185). The statutes of Banbury School allowed girls to receive vernacular education in the petty classes up to the age of nine.

As an organised system of education began to take shape, schools provided the first step towards a variety of careers. However, Elizabethan policies aimed to

restrict men to the callings of their fathers, to consolidate the social order by maintaining due differences between estates; accordingly there were moves to reserve certain forms of education to gentlemen at one end of the scale while at the other the children of the poor were trained to habits of useful work (Simon 1966:294).

The teachers

In 1559 Elizabeth's first parliament empowered her to issue new statutes for the cathedrals and schools which had been established under Henry, Edward and Mary. A new set of royal injunctions to the clergy largely endorsed previous policies, including the licensing of teachers:

No man shall take upon him to teach but such as shall be allowed by the ordinary [i.e. the bishop], and found meet as well for his learning and dexterity in teaching, as for sober and honest conversation, and also for right understanding of God's true religion (quoted in Orme 2006:333).

This rule was incorporated into the canon law of the Church of England in 1571 and endorsed in 1604, when those applying for a licence to teach - whether in a public school or a gentleman's household - were required to subscribe to the royal supremacy, the Thirty-nine Articles and the Book of Common Prayer. Unlicensed teaching could result in fines or imprisonment.

The licensing of schoolmasters by the diocesan bishops, says Orme, 'was now an important part of state control of society. It was widely implemented down to the eighteenth century and did not finally disappear until 1869' (Orme 2006:333-4). Bishops were given this responsibility partly because there was no other convenient authority to undertake the task, and partly 'because education was still regarded as essentially a religious activity' (Lawson and Silver 1973:101).

Women teachers were also required to have ecclesiastical approval, though 'they do not seem to have been formally licensed and rarely appeared at visitations' (Lawson and Silver 1973:102).

The system of visitations 'was not always effective in enforcing the law' (Lawson and Silver 1973:102):

Examination of schoolmasters was unsystematic. Unlicensed masters certainly operated, some of them religious dissentients, either puritans or secret papists. But the rapid acceptance of the new Anglican settlement by the nation as a whole must be attributed at least partly to the cumulative teaching of orthodox schoolmasters approved and supervised by the bishops (Lawson and Silver 1973:102).

Schoolmasters were now subject to examination - along with the clergy - at visitations, and there were special inquiries into the running of schools, especially where there was a crown stipend, which could be withheld 'if the master's outlook was in question' (Simon 1966:312).

Rosemary O'Day argues that teaching was beginning to be seen as an important function, partly because more laymen were now attending the schools and universities, and partly because the teacher 'was responsible for the success of the humanist and Protestant programmes' (O'Day 1982:166).

Humanists were anxious to control the curriculum and teaching methods. Thus Roger Ascham's The Scholemaster, published posthumously in 1570, was a 'teach yourself' manual which did away with the need for a teacher altogether. It aimed to provide a 'plain and perfect way of teaching children to understand, write and speak, the Latin tongue'. Ascham's commitment to teacher training was 'less certain than his commitment to humanist content and methods' (O'Day 1982:166).

The emphasis was upon a standardised curriculum, method and purpose. When good teachers were few on the ground the printed book could come to the rescue. Even in Richard Mulcaster, writing much later than Ascham and often regarded as the archetypal professionaliser of early modern education, we see this fear of the individual and of experimentation in teaching. Early writers on education advocated the most rigid kind of control over the content of the curriculum (O'Day 1982:166-167).

In any discussion of the professionalisation of teaching in this period, Richard Mulcaster's ideas 'must assume pride of place' (O'Day 1982:167). Mulcaster was headmaster of Merchant Taylors' School, London from 1561 to 1586 and of St Paul's School from 1596 to 1608. He also held an ecclesiastical living. 'He advocated uniformity in both curriculum and method and laid down an acceptable curriculum for both petty and grammar schools' (O'Day 1982:167).

He proposed the establishment of a teacher-training college in which students would be divided into groups of potential elementary, grammar and university teachers. They would receive instruction in the classics and in appropriate teaching methods.

Mulcaster believed that elementary education was important for the success of the humanist programme and therefore argued that elementary teachers should be paid more than teachers in the upper forms of the grammar schools.

However, the professionalisation of teaching was hindered by the view that it was a suitable sideline for the clergy. Unlike the church, teaching was

institutionally weak and organisationally stunted. There was no built-in network for the dissemination of the theories or practical advice of Mulcaster, Clement, Coote, Brinsley and Hoole. There was no mechanism for controlling the recruitment of teachers over the nation as a whole or even within one area (O'Day 1982:170).

The grammar schools

Elizabeth's reign saw a large increase in the number and size of grammar schools. They mostly educated the sons of the middle classes - yeomen, substantial husbandmen, merchants, successful tradesmen and artisans, clergy, apothecaries, scriveners and lawyers. 'Probably very few boys came from that half of the population made up of the labouring poor' (Lawson and Silver 1973:116).

The majority of Elizabethan grammar schools provided a basic grounding in English, the scriptures and the classics. 'The grammar schools must have contributed much towards developing the uniform speech of an educated class' (Simon 1966:364-5).

Religion continued to be important: school founders and governors, concerned about the encroachment of the Jesuits, 'bent their efforts to arming scholars with sound protestant precepts' (Simon 1966:366).

The larger schools began to expand the curriculum, adding arithmetic or cosmography, history and music. A few even taught modern languages. They employed more professional teachers and used the new printed books.

A new official grammar was printed in London, but otherwise most of the books available to schools during Elizabeth's reign came from the European centres of reform. Prominent among these were the 'colloquies' (dialogues) of Castellion and Cordier, from Geneva, which replaced those of Erasmus and Vives in many schools. Greek - and later Hebrew - began to be taught, first in leading schools and then more widely; and the introduction of annual examinations, 'presided over by scholars of note, contributed considerably to raising standards' (Simon 1966:305).

However, most grammar schools were untouched by humanist ideals and offered little more than 'a narrow, arid, linguistic grind' (Lawson and Silver 1973:118). Grammar masters regarded the teaching of writing as beneath their dignity, and the teaching of number was 'even more neglected' (Lawson and Silver 1973:118). Indeed, in his guide for young schoolmasters, John Brinsley warned that

you shall have scholars, almost ready to go to the university, who yet can hardly tell you the number of pages, sections, chapters, or other divisions in their books, to find what they should (quoted Lawson and Silver 1973:118).

The statutes of some schools prescribed half-days for physical exercises and games, though football, 'whose contemporary horrors Elyot had so eloquently described' (Simon 1966:365), was not favoured. Newer schools often had their own playing fields, and military training was sometimes included in the curriculum.

Boys usually attended the grammar schools from around the age of seven or eight. Some left to go on to university at fourteen or fifteen, but most probably left earlier either to start work or to be apprenticed.

As to the organisation in the classroom:

All were taught together in the one schoolroom, but divided into forms sitting on benches ranged along the two long walls. The master sat enthroned on a dais at the top end teaching the older forms (the upper school), whilst the usher taught the younger forms (the lower school) at the end near the door, where he could observe their goings out and comings in (Lawson and Silver 1973:118).

The school day was long and corporal punishment was common - 'Teaching and beating were interchangeable terms' (Lawson and Silver 1973:118). There were frequent complaints about the brutality of schoolmasters.

In addition to the holidays at Christmas, Easter and Whitsuntide (amounting to around six weeks a year), there were sometimes day or half-day holidays, when the boys amused themselves with 'balls, tops, battledores, archery, cock fighting, fighting one another or climbing on the roof of the church, to which the schoolhouse was usually adjacent' (Lawson and Silver 1973:119).

The gentry continued to exert considerable influence in the schools 'from positions on governing bodies or through powers to appoint masters' (Simon 1966:361). Wakefield's school, for example, had 'not only the arms of the Savilles over the door but those of other gentlemen in the windows ... Here instructions to the master insist on methods of teaching at length, deprecating too academic an approach' (Simon 1966:361).

Nonetheless, the grammar schools did not suffer, as the colleges had, from being 'recast in the gentleman's image':

Within their walls, as Mulcaster had desired, 'the cream of the common' did come to associate with the rest so that in this sense too schools made their contribution towards moulding a common outlook (Simon 1966:368).

Founders of grammar schools often linked their schools with particular colleges, as Wykeham (Winchester and New College, Oxford) and Henry VI (Eton and King's College, Cambridge) had in the previous century. Thus Westminster's new charter of 1560 associated the school with Christ Church, Oxford and Trinity College, Cambridge; and Alexander Nowell linked his school at Middleton in Lancashire (1572) with Brasenose, Oxford. Similarly, St. John's College, Oxford, founded by Sir Thomas White, reserved thirty-seven places for pupils of the Merchant Taylors' School in London (Charlton 1965:131).

The petties

The great mass of the population, especially in rural areas, lived in grinding poverty as servants, labourers, cottagers and paupers. It would have been impossible for them to pay school fees, and equally difficult for them to do without their children's earnings or labour.

In any case they had little incentive, for schooling offered few returns: the daily round of physical drudgery left no time or energy for reading, there was no occasion for writing, and small chance of self-advancement in a stratified and apparently changeless social order (Lawson and Silver 1973:111).

Nonetheless, the demand for schooling for the poor - and for younger children - was beginning to grow. As a result, the number of schools increased and there was 'a bewildering variety of forms, ranging from instruction by priests to private adventure schools, often as a sideline to shopkeeping and trade' (Williams 1961:133).

Many of the 'petties' or 'ABCs' were proper schools, attended by both girls and boys. In other cases, grammar schools began to provide for classes of 'petties' to be taught by an usher or an older pupil. An example of this can be seen in the school established by Archbishop Parker in 1569 in connection with Eastbridge Hospital, Canterbury. Here, a master was appointed 'to teach twenty poor children to read, write and sing' (Simon 1966:313); books, pens, ink and paper were supplied free of charge; and boys were not allowed to stay at the school for more than four years, so as to make room for others.

During Elizabeth's reign the petties increased in number and there was some improvement in quality, especially when ushers began to be appointed, 'though as might be expected such instruction came low in the order of priorities' (Charlton 1965:99). There was greater focus on the 3Rs, although arithmetic - 'cyphering and casting of accounts' - was 'not yet generally considered essential in this context' (Charlton 1965:100). Neither was much attention paid to drawing and music. The reason for this, Charlton argues, is that the purpose of this pre-grammar school education was basically religious in aim:

The immediate and perhaps most important purpose of learning the arts of reading and writing was to enable the child to master the elements of his religious life, the Lord's Prayer, the Ten Commandments, the Creed and the Seven Sacraments (Charlton 1965:101).

Some now began to call for improvements in the teaching of young children. In his Elementarie (1582) Richard Mulcaster called for 'a perfit English dictionarie' which would contain 'all the words which we use in our English tongue whether material or incorporate, out of all professions, as well learned as not, and besides the right writing, which is incident to the alphabet, would open into as therein both their natural force and proper use' (quoted in Charlton 1965:102).

In 1587 Francis Clement produced a practical manual for those who taught reading, writing, spelling and arithmetic in the petties. It gave instructions for making ink and explained how to choose a quill and cut it. It had what must be one of the longest titles in history:

Petie Schole with an English Orthography, wherein by rules lately prescribed as taught a method to enable both a childe to read perjectly within one moneth and also the imperfect to write English aright. Hereto newly added 1. verie necessorie precepts and patterns of writing the secretary and Romane hands. 2. to number by letters and figures. 3. to cast accompts (quoted in Charlton 1965:104).

In 1588 William Kempe published his Education of Children in Learning, and in 1596 Edmund Coote addressed his book The English Schoolmaster to 'such men and women of trades (as tailors, weavers, shopkeepers, seamsters and such other) as have undertaken the charge of teaching others' (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:113). There was clearly a considerable demand for it: a twenty-fifth edition appeared in 1635 and a fifty-fourth in 1737 (Charlton 1965:104).

John Brinsley developed a method of teaching reading, and assured the would-be petty teacher: 'thus may any poor man or woman enter the little ones in a town together and make an honest poor living of it, or get somewhat towards helping the same' (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:113).

Charles Hoole deplored the poor level of basic skills of grammar school entrants and wrote with the object of improving the teaching in the petties. Such teaching, he argued, was too important to be 'left as a work for poor women, or others, whose necessities compel them to undertake it, as a meer shelter from beggary' (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:113).

Interestingly, all these writers - Mulcaster, Kempe, Coote, Brinsley and Hoole - were grammar school masters, so their books demonstrate the growing recognition of the importance of the elementary stage of education in the vernacular, half a century or more before the followers of the Czech Moravian pastor John Amos Comenius (1592-1670) began work in this country.

In addition to the petties, two other types of school began to develop, catering for both children and adults. In the writing schools, scriveners taught their skills, sometimes peripatetically around villages and hamlets; while in the cyphering schools pupils learned arithmetic and related skills such as mensuration, surveying and the casting of accounts. The aim of these schools was to meet the secular needs of a society in which trade was now expanding rapidly and whose administration was becoming more complex. The two sometimes merged to become 'English schools', where the age range of the pupils was closer to that of the grammar schools.

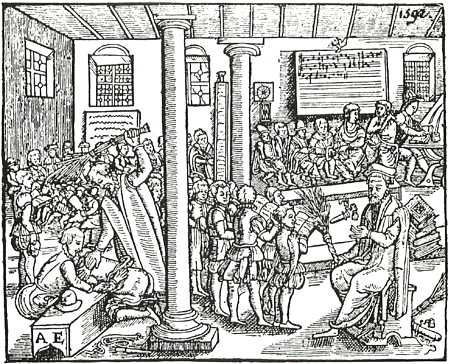

An Elizabethan schoolroom

from a woodcut, 1592

Rosemary O'Day provides the following description of this schoolroom:

One schoolroom shows five groups of boys rehearsing their lessons. One of these groups is reading from individual books and being heard by the master. A boy (perhaps a senior pupil or an usher) is reading to a small group of children with hornbooks in their hands. An usher appears to be teaching number of some kind to boys at the back of the room, while another group may be seen reciting or engaging in a spelling-bee while their teacher writes at a desk. In the left-hand foreground a couple of boys are being whipped on their bare buttocks. The range of visual aids which the room contains suggests that these played a real role in the teaching of the young. In the left-hand corner of the back of the room a large sheet of paper is hung on the wall, which bears writing of some kind. On the wall in the right-hand back corner are a clock face, an hour glass and a music score. The usher is standing before a tall and narrow board and writing upon it for the benefit of the boys behind him (perhaps demonstrating the casting of accounts) (O'Day 1982:59).

We cannot be sure, says O'Day, that the typical Elizabethan schoolroom was always as cramped and crowded as this picture suggests, but the pupil-teacher ratio was often high and the noise level must have been stressful. Group teaching appears to have been common, often using a board or a variety of visual aids - 'the picture alphabet, flash cards, illustrated books, religious pictures, diagrammatic explanations of difficult concepts ... and the tactile counting frame' (O'Day 1982:59).

The plight of the poor

In 1570 the city of Norwich found that a tenth of its population was destitute and made arrangements for children 'whose parents are not able to pay for their learning' to be taught spinning and other skills so that 'labour and learning shall be easier than idleness' (Simon 1966:370). Referring to the scheme, which lasted for a decade or more, Thomas Wilson observed that English citizens were not allowed to be idle like those in other parts of Christendom 'but every child of 6 or 7 years old is forced to some art whereby he gaineth his own living and something besides to help to enrich his parents or master' (quoted in Simon 1966:370).

Labourers earning threepence (about 1p) a day and husbandmen who needed their children's help to support the family could not afford the grammar school. While the actual teaching was often free, there were many incidental charges: 'books, writing materials, wax candles, added up to a considerable sum' (Simon 1966:370).

In 1572 the government ordered censuses of the poor in all cities and introduced a compulsory poor rate. Late Tudor poor relief legislation, says O'Day, built on existing ideas. 'Little that was new was introduced and the legislation itself floundered upon the inability of Tudor or Stuart officials to operate it efficiently' (O'Day 1982:248).

While the Elizabethan gentry 'offered little in the form of endowments for schools by comparison with the benefits they received' (Simon 1966:372), merchants, whose wealth was growing, endowed schools generously, though Mulcaster maintained that their benefactions were meagre compared with the money they made from the poor. And if the poor were effectively paying for the grammar schools - via the merchants - they gained little benefit from them, since most of the pupils were the sons of the wealthier yeomen farmers, burgesses, country gentry and professional men, including ministers of the church. There was scarcely any funding to enable poor boys to attend the grammar schools.

However, new educational opportunities were being created in the schools being set up by boroughs and townships, and by the increasing number of books being published in English.

The stream of books in English, which had reached respectable proportions in Edward's reign, had by the close of the century become a flood, giving the ordinary citizen an established share in the spread of knowledge (Simon 1966:383).

The demand for education continued to grow. Where there was no foundation or parish school, 'local farmers clubbed together and made arrangements to invite a master as towns had earlier done, taking him in to board in turn' (Simon 1966:383). Ecclesiastical visitors were sometimes 'scandalised to find communion tables, which had been pressed into the service of education, stained with ink' (Simon 1966:383).

Contemporary views on education

Despite all these developments, Roger Ascham (1515-1568), who had been Elizabeth's teacher and was one of the most notable educationists of the period, still believed that education was not being accorded the status it deserved. In his book The Scholemaster, published posthumously in 1570, he wrote:

it is pitie, that commonlie, more care is had, yea and that emonges verie wise men, to finde out rather a cunnynge man for their horse, than a cunnyng man for their children. They say nay in worde, but they do so in deede. For, to the one, they will gladlie giue a stipend of 200. Crounes by yeare, and loth to offer to the other, 200. shillinges. God, that sitteth in heauen laugheth their choice to skorne, and rewardeth their liberalitie as it should: for he suffereth them, to haue, tame, and well ordered horse, but wilde and vnfortunate Children: and therfore in the ende they finde more pleasure in their horse, than comforte in their children (Ascham 1570:193).

Ascham stressed the importance of play in education. 'The Scholehouse should be in deede, as it is called by name, the house of playe and pleasure, and not of feare and bondage.' (Ascham 1570:176) He set up his own school, funded by Richard Sackville, who had been prominent in educational matters in Edward's day.

Another writer who expressed some surprisingly progressive views (for the time) was Richard Mulcaster. In 1581, with twenty years' experience at the Merchant Taylors' School behind him, he published his book Positions, wherein those Primitive Circumstances be Examined, which are necessary for the training up of children, either for skill in their booke, or health in their bodie. In it he mocked humanist plans for a classical education from the nursery onwards, and said education should be regarded as a developing science.

He argued that it was possible to create a balanced educational course which should be taught in all schools. All children should be taught to read in the vernacular, to write, draw and sing, before starting on academic studies. There should also be physical exercise and training. Gentlemen's children, he said, were no different from others - 'their wits be as the common, their bodies of times worse' (quoted in Simon 1966:353) - so they should follow the same course, not in a humanist academy but in the grammar school, where gentlemen could mix with each other and with 'the common'.

Mulcaster noted that more schools had been opened during Elizabeth's reign than had existed before it, but that poor parents could still not afford an education for their children, who were sent to work from an early age. This, he argued, was probably just as well because if the poorest were sent to school 'they will not be content with the state which is for them, but because they have some petty smack of their book they will think any state, be it never so high to be low enough for them' (quoted in Simon 1966:369).

Joan Simon argues that the growing criticism of schools at the end of the sixteenth century demonstrates the coming of age of the bourgeoisie. She quotes John Brinsley, a teacher, who told of a dissatisfied parent complaining that 'my son comes on never a whit in his writing. Besides his hand is such, that it can hardly be read; he also writes so false English, that he is neither fit for trade, nor any employment wherein to use his pen' (Simon 1966:397).

The schools may have had their faults but 'there is a clear line of development to be traced' (Simon 1966:400): Vives had urged schoolmasters to become 'custodians of the treasury of their language'; Mulcaster had written a book on the writing of English; and others had 'followed suit in a variety of ways - compiling vocabularies, dictionaries, grammars - for there had been a ceaseless and exuberant development of the language and the overriding task was to reduce it to order' (Simon 1966:400).

Other forms of education

Apprenticeships

Craft apprenticeship had already become an important element in the provision of technical and commercial training. In London and the larger towns, boys from around the age of fourteen were accepted as apprentices by the various guilds, provided they were literate and could afford the fees.

Apprentices came from the middle social groups - substantial burgesses, yeomen, craftsmen and the younger sons of the gentry - and in London they were drawn from all parts of the country. They were fed, clothed, housed and taught by their master in his own house and workshop, and often they formed a noisy, boisterous and even turbulent element in urban society (Lawson and Silver 1973:123).

With the increasing criticism of the limited curriculum of the grammar schools - based as it was on the requirements of the universities and the learned professions - apprenticeships in crafts and trades now became more popular, and were standardised in the Statute of Artificers of 1562.

Unfortunately, one of the key features of this period was the concern to protect the status of gentlemen. A list of 'Considerations' drawn up for submission to parliament at the start of Elizabeth's reign demonstrates this thinking. With the dispersal of monastic lands now well under way, one clause of the Considerations proposed that yeomen should be prohibited from buying lands worth more than £5, butchers and tanners £10, and merchants £50. Similarly, the interests of gentlemen should be protected by reserving suitable educational facilities for them:

'A third of the free scholarships at universities' should be set aside for 'the poorer sort of gentlemen's son' and yeomen should be prevented from entering sons at the inns of court - only those 'immediately descended from a nobleman or gentleman' should be permitted to study either common or civil law (Simon 1966:335).

Some of the proposals in the Considerations were not enacted, but the 1562 Statute severely restricted the opportunities of different sections of the population. Clothiers, for example, were forbidden to take apprentices. And while the Statute did establish a national system of apprenticeship, it was also designed to cope with the growing problem of poverty and vagrancy. As a result, apprenticeship 'came to be extended to semi-skilled occupations that really required little or no technical training, and where the apprentice might be no more than an unpaid juvenile labourer' (Lawson and Silver 1973:123). It was this kind of apprenticeship to which pauper children were bound, especially after the Elizabethan Poor Law (Acts passed between 1597 and 1601) ensured that the children of the poor were set to work or 'drifted into the poorest trades as cheap unskilled labour' (Simon 1966:336).

The chivalric system and the courtly academies

Meanwhile, the upper classes, who wanted their sons trained for posts at Court, for diplomacy and for higher appointments in the army, turned again to the chivalric system of education, which enabled noble families to send their young sons to be pages at great houses and undergo a course of training for knighthood.

The most influential of the great households was that of Lord Burghley, Elizabeth's Secretary of State and Chancellor of Cambridge University. From 1561 he was responsible, as master of the court of wards, for the upbringing of orphaned young noblemen who were the royal wards; he also took in other gentlemen's sons. The studies which Burghley prescribed

set a new standard in aristocratic education: the 12-year-old earl of Oxford in 1562 learnt dancing, French, Latin, writing, drawing and cosmography, with riding, shooting and more dancing on holidays (Lawson and Silver 1973:133).

An English version of The Book of the Courtier by Baldassare Castiglione (1478-1529), originally published in Venice in 1528, appeared in 1561 and became 'almost a second bible for English gentlemen' (Simon 1966:340). But, as Roger Ascham pointed out, Castiglione was soon cast aside in favour of 'superficial courtly guides and the aping of foreign fashions' (quoted in Simon 1966:340). At the request of Sir Richard Sackville, Ascham again set out the case for combining learning with sound religion in The Scholemaster.

Meanwhile, in France and in the German and Scandinavian states, knightly or courtly academies were being founded to give instruction to young nobles, not only in horsemanship and the use of arms, but also in modern languages, history and geography, and in the application of mathematics to military and civil engineering.

A proposal for the establishment of an academy on these lines in England was made by Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1570. Gilbert argued that gentlemen's sons were deprived of 'a sound and godly education' by the system of wardship. Most wards, he said, were brought up 'in idleness and lascivious pastimes, estranged from all serviceable virtues to their prince and country' (quoted in Simon 1966:341). Their education was meagre. He proposed the setting up of an academy in London for wards aged twelve to twenty, where they would be taught - in English - 'arithmetic and natural philosophy, cosmography and navigation, military sciences as well as arts, modern as well as ancient languages', plus history, politics and civil law (Simon 1966:343). But Gilbert's scheme was too expensive and did not come to fruition.

So courtly academies were never established in England as they had been elsewhere in Europe. Young children were still sent away to be brought up in the households of others, though concern was growing about the wardship system. 'Those of influence and means provided heirs with a prolonged training of the best they could devise. But younger sons must make their way in a trade or profession' (Simon 1966:367).

Foreign travel became important for gentlemen. Philip Sidney, for example, son of the Lord President of the Council in Wales, had been educated at Shrewsbury school and then spent a year at Christ Church. In 1572, at the age of nineteen, he was 'dispatched on his travels with a sound protestant tutor and three servants' (Simon 1966:347). His tour lasted almost three years and 'shaped a young man ... who became, despite all the embroidery on the theme of Gloriana, a symbol of the age, and his influence was immense' (Simon 1966:348).

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, writers had complained about 'the cultural backwardness of young men of birth, their lack of education, addiction to hunting, hawking, idle pleasures, and the irresponsibility of their parents' (Simon 1966:366). They were still complaining a hundred years later. However, Joan Simon argues that profound changes had taken place during the century:

Country houses had attained a new level of civilisation, usually housed a tutor and sometimes sponsored a variety. University-trained men were much less rare than formerly in vicarages, while there were other well-qualified masters in charge of established local grammar schools. Young gentlemen were now to be found not only under tuition at home and in residence at colleges but also at their desks in the new school buildings up and down the country (Simon 1966:366).

By the time Elizabeth died, in March 1603, teaching was beginning to attain a higher status and 'there were dedicated teachers who took a pride in their profession' (Simon 1966:403). Education was now seen as a way of preparing men for particular functions - 'a concept corresponding to the growing specialisation of knowledge and the development of professions' (Simon 1966:402). Non-specialised 'liberal' education had become 'the hallmark of gentility, preserving the forms of a humanist education emptied of the essential content' (Simon 1966:402).

Williams points out that the existence of these three distinct types of education - apprenticeships, the chivalric system, and the academic system -

reminds us of the determining effect on education of the actual social structure. The labouring poor were largely left out of account, although there are notable cases of individual boys getting a complete education, through school and university, by outstanding promise and merit. For the rest, education was organised in general relation to a firm structure of inherited and destined status and condition: the craft apprentices, the future knights, the future clerisy (Williams 1961:131).

The Inns of Court

The common pattern of education for gentlemen of wealth and influence, especially for those planning to enter parliament, was a year or so at Oxford or Cambridge followed by a period of training at the Inns of Court. The results can be seen in the parliament of 1584: 300 of its 460 members were newcomers, most of them gentlemen. Education was now seen as 'a worthwhile investment' and 'there was a growing tendency to regard the House of Commons - filled as it was with gentlemen's heirs - as another kind of finishing school' (Simon 1966:357).

The Inns of Court had had their origins in the early thirteenth century when groups of lawyers had begun to rent accommodation near the royal courts of law. These gradually developed into the four 'greater' Inns: Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple and Middle Temple. Lawyers began to think of themselves as a profession, and felt a sense of responsibility for the training and behaviour of their younger members, the addiscentes apprenticii (Charlton 1965:170).

The Inns provided a long and comprehensive training - up to twelve years for a barrister. Students took part in conferences, disputations and pleadings and heard leading barristers and judges at Westminster Hall.

However, the sixteenth century saw a decline in standards for three main reasons.

First, because it was a litigious age, the profession of the law flourished and many members of the Inns were too busy to arrange exercises for their students. 'The result was a high degree of absenteeism' (Charlton 1965:184).

Second, as the number of students increased, their behaviour deteriorated:

There can be no doubt that the attitude of a large number of students at the Inns of Court to their work and their behaviour in and out of the Inns left much to be desired. Taking into account the natural joie de vivre of young men, the records nevertheless show that this was rarely offset by a parallel devotion to study at the appropriate times. Again, the members were generally older than their university counterparts, many having come to the Inns from university, and their behaviour was often dangerous and sometimes vicious. Fighting, theft and licentiousness often appear in the records (Charlton 1965:177).

And third, there was a 'mass invasion' of the Inns of Court by the gentry, as there had been at the universities, so that the Inns were full of young gentlemen who had no intention of practising the law. From the 1560s onwards, attendance became a matter of course, 'especially for elder sons who would eventually inherit estates and responsibilities as justices and members of Parliament' (Lawson and Silver 1973:134). As a result, the Inns became more socially exclusive than the universities.

By the end of the century the decline had been arrested, so that Sir Edward Coke, a senior lawyer who rose to become Attorney General, could declare London 'the third university of England', and the Inns of Court 'the most famous university for profession of the law only, or any one humane science, that is in the world' (quoted in Simon 1966:355). And Ben Jonson dedicated his satirical comedy Every Man out of his Humour (1599) to the Inns as 'the noblest nurseries of humanity and liberty'.

However, it is perhaps worth noting Charlton's warning that these descriptions give the Inns 'an exaggerated place in the history of what we call a liberal education' (Charlton 1965:195).

Gresham College

Sir Thomas Gresham (1519-1579), a member of the Mercers' Company, had risen to become 'the wealthiest English merchant' (Watson 1921:756). In his will, he left his mansion house in Bishopsgate to the Mercers' Company and the City Council of London, to be used as a college. A further bequest was made to provide salaries of £50 a year for seven professors: the City of London Corporation were to appoint professors of Divinity, Astronomy, Music and Geometry; the Mercers' Company professors of Law, Physic and Rhetoric.

The college was founded after Lady Gresham's death in 1596.

Gresham's will required that the lectures in Divinity should endorse the 'truth of doctrine of the Church of England' and condemn the 'false opinions of the Papists' (quoted in Watson 1921:756). The Professor of Astronomy was to lecture on the 'principles of the sphere, the theoriques of the planets, and the use of the astrolabe and the staff, and other common instruments for the capacity of mariners, which, being read and opened, he shall apply them to use by reading geography and the art of navigation' (quoted in Watson 1921:756).

The professors were urged to bear in mind that those attending their lectures would be 'merchants and other citizens'.

Fifty years later, during the period of the Commonwealth (1649-1660), Gresham College would become the meeting place of the group of scientists who formed the Royal Society.

The universities

The universities and the crown

During Elizabeth's reign

the universities were gradually converted into strongholds of the new state religion, notwithstanding the fact that they both harboured minorities of religious extremists, both Catholic and puritan (Lawson and Silver 1973:102).

The last royal visitation of the universities, in 1559, was aimed at reversing the changes of Mary's reign. After that, it was their Chancellors - Leicester at Oxford, Cecil at Cambridge - who exercised political control.

In order to ensure religious discipline and uniformity, from 1563 all graduates had to take the Oath of Supremacy. Oxford went further: it imposed additional tests and required every student to reside in a college or hall and to be officially matriculated by the university. The effect was that 'the university was closed to all but Anglicans' (Lawson and Silver 1973:102). Cambridge - 'much more puritanical and critical of the new church than Oxford' (Lawson and Silver 1973:102) - required only the Oath of Supremacy on graduation until 1616.

The universities were incorporated in the 1571 Oxford and Cambridge Act, which began by declaring 'the great zeal and care that the lords and commons of the present parliament have for the maintenance of good and godly literature and the virtuous education of youth' (quoted in Simon 1966:318). The universities now became public corporations. Their charters confirmed 'privileges, liberties and franchises' which 'were seen to derive from the Crown (in Parliament) alone' (O'Day 1982:79).

Attempts were made to reduce puritan influence, including a new code of statutes for Cambridge in 1571, but in the following years French and German scholarship - particularly the logic of Petrus Ramus, the French humanist - began to have an effect on the schools. Lawrence Chaderton, fellow of Christ's, the chief centre of Puritanism, was the leading protagonist of Ramus at Cambridge. The university was soon supplying Ramist teachers to grammar schools. In 1588 William Kempe, master of Plymouth School, published The Education of Children in Learning, which set out a method of teaching logic and rhetoric based entirely on Ramus. Other Ramist books followed.

This created an 'uneasy relationship between the universities and the Church during the sixteenth and, particularly, the seventeenth centuries' (O'Day 1982:78). While the church continued to use the universities for the training of its ministers, its hierarchy was now 'unable to assert direct institutional control over the teaching institutions themselves' (O'Day 1982:78). As a result, the universities were free to criticise the established church and to introduce 'elements of both curriculum and life which seemed iniquitous to the hierarchy' (O'Day 1982:78).

There was greater interest in the universities among the aristocracy and the gentry during this period. Young gentlemen who were not seeking degrees or intending to enter a profession were still sent to Oxford and Cambridge, and there were increasing concerns about patronage, much of which originated with the crown.

In 1579 the Cambridge Vice-Chancellor and others complained to the Chancellor about the crown's interference whereby 'the rewards of merit and studiousness are withheld, scholars being induced to look for preferment to the favour of courtiers rather than to their true deserts at the hands of the university' (quoted in Simon 1966:359).

Various attempts were made to curb corruption, including Sir Thomas Smith's 'Act for the Maintenance of Colleges' in 1576.

The students

The population of the universities increased and changed during Elizabeth's reign. Lawson and Silver argue that

In no field of education was change so marked as in the universities. Most important so far as English society was concerned was the spectacular growth of the university population and its changing social composition (Lawson and Silver 1973:126).

With residence now compulsory, the colleges filled to overflowing and fee-paying commoners or pensioners outnumbered the foundation members - the fellows and scholars. The student population was socially mixed and represented all levels of society, other than the great mass of the poor, though rich and well-born students 'formed a much larger proportion from the 1560s' (Lawson and Silver 1973:127).

Overall numbers peaked around 1580 when Oxford and Cambridge together had some 3,000 students. Cambridge appears to have been the more popular; it was also the more influential, both politically and ecclesiastically. To meet the rising demand for places, colleges expanded by annexing neighbouring houses or by adding attic storeys or additional quadrangles; some of the older colleges - like Oriel - replaced their medieval buildings with new ones on a grander scale; and new colleges were founded.

Matriculands fell into three main categories and it has been estimated (Lawson and Silver 1973:127) that between 1575 and 1639 about half were from the gentry (peers, knights, esquires, gentlemen, and those who aspired to gentility, such as city merchants, lawyers and physicians), about 40 per cent were plebeians (sons of urban shopkeepers, small farmers and lesser professional men such as apothecaries and attorneys), and the remaining ten per cent were the clergy (the largest single professional group).

Most students joined the colleges as commoners, though the wealthiest and most powerful entered as fellow or gentlemen commoners, paying extra fees for special privileges. 'Class distinctions and social deference thus became marked features of college life' (Lawson and Silver 1973:127).

A German visitor to Oxford in 1598 observed that in college halls 'earls, barons, gentlemen, doctors and masters of arts, but very few of the latter' were admitted to the top table, 'masters of arts, bachelors, some gentlemen and eminent citizens' occupied a second table, whilst a third was for 'people of low condition' (Lawson and Silver 1973:127).

Few of the upper-class students had serious academic interests - many stayed for only a year or so and then moved on to one of the Inns of Court. There were many complaints about their invasion of colleges originally intended for poor scholars. The topographer William Harrison, for example, wrote in 1577:

poor men's children are commonly shut out, and the richer sort received (who in time past thought it dishonour to live as it were upon alms), and yet, being placed, most of them study little other than histories, tables, dice, and trifles, as men that make not living by their study the end of their purposes ...

Besides this, being for the most part either gentlemen or rich men's sons, they oft bring the universities into much slander. For, standing upon their reputation and liberty, they ruffle and roister it out, exceeding in apparel and haunting riotous company ... and for excuse, when they are charged with breach of all good order, think it sufficient to say that they be gentlemen (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:127-8).

However, opportunities for poor scholars began to increase, partly as a result of new scholarships at schools and colleges, and partly because wealthy members needed servants:

Many poor students were thus admitted as servitors (sizars at Cambridge) and as such earned their board and tuition by working as college porters, waiters in hall, Bible clerks in chapel, and servants of fellows and gentlemen commoners (Lawson and Silver 1973:128).

The colleges

The colleges were transformed from exclusive societies of graduate fellows into educational establishments for large groups of adolescent boys. Furthermore, the system of public lectures by regent masters was gradually replaced by private tuition from college fellows.

Thus, in time the colleges almost entirely superseded the university as the source of instruction. They also became responsible for admitting students to the university, which simply matriculated those whom each college presented. And as the importance of the colleges grew, so did the importance of their heads, who collectively became a new force in university government (Lawson and Silver 1973:129).

These changes were recognised by revised statutes at Cambridge in 1570 and at Oxford in 1636. 'Each university was in process of being subordinated to its component parts, the colleges' (Lawson and Silver 1973:129).

University studies

The undergraduate course consisted of Latin and Greek classical studies, which was the sort of training lay gentlemen required for public service.

From the 1590s, however, 'scholasticism revived and Aristotelian logic and philosophy shared the curriculum with classical humanism' (Lawson and Silver 1973:129). This probably held little appeal for some of the young gentlemen, who preferred to spend their time vaulting or fencing, playing the viol or flageolet, or simply behaving badly. However, most students still trained for the church: they obtained their BAs and went off to become rural parish priests.

Theology was by far the most important of the higher faculties, though medicine was now attracting more students than before, particularly at Cambridge.

Despite the crown's desire that the universities should enforce Anglican uniformity, they 'nurtured religious dissentients of many kinds' (Lawson and Silver 1973:131). Catholicism had practically disappeared from Oxford by 1580, but in both universities various puritan groups worked for 'a godly reformation within the Church of England' (Lawson and Silver 1973:131).

Although philanthropists generally favoured founding colleges, fellowships and scholarships, they also benefited the universities themselves. Thus at Oxford

In 1602 Sir Thomas Bodley restored the university library, defunct since the 1550s, and subsequent gifts, including the right to receive a copy of every book newly printed in the country, soon made it the greatest library in the kingdom (Lawson and Silver 1973:130).

The university appointed its own printer in 1585, built a new schools (lecture rooms) quadrangle and established a botanic garden.

Some puritan critics of the 'clerical, scholastic and ruling-class connections' (Lawson and Silver 1973:132) of Oxford and Cambridge called for the establishment of a third university. The Inns of Court were considered, but 'they too were a gentlemen's monopoly' (Lawson and Silver 1973:132). Schemes for a northern university - in Ripon - were proposed several times, but came to nothing.

Education in Scotland

By the mid 1500s, most Scottish towns were well provided with grammar schools, controlled by the burgh councils:

Edinburgh, for example, had three, all with early sixteenth-century origins. Edinburgh High School is first mentioned in 1503, Canongate in 1529 and South Leith in 1521. Such schools varied in size. In 1587 Perth Grammar School had 300 pupils. The Royal High School, Edinburgh, was also large. Both Canongate and South Leith were considerably smaller (O'Day 1982:230).

The universities, however, were 'almost totally emasculated, with very few students, buildings in ruins and severely plundered funds' (O'Day 1982:220).

The New Kirk and the civil government set out to provide 'universal general instruction in the rudiments of learning and the elements of the Protestant faith as a bulwark against the re-emergence of Catholicism in their midst' (O'Day 1982:220).

In May 1560 the First Book of Discipline set out the reformers' plans for both schools and universities. Based on the work of John Knox (c1513-1572), it proposed that education should be provided at three stages - primary, secondary and university. It called for the establishment of a school in every parish, and for every important town to have a schoolmaster able to teach grammar and Latin. In country districts, a reader or minister was to 'instruct the children and youth of the parish in their rudiments, and especially in the Catechism or elements of religion' (Dickson 1921:1496); while in every notable town there was to be established 'a college in which at least logic and rhetoric, together with the tongues, were to be taught' (Dickson 1921:1496).

The motivation behind the scheme was religious, as John Knox had indicated in 1556:

For the preservation of religion it is most expedient that schools be universally erected in all cities and chief towns, the oversight whereof to be committed to the magistrates and godly learned men of the said cities and towns (quoted in O'Day 1982:223).

And the proposed curriculum was utilitarian:

A certain time must be appointed to reading and learning of the catechism; a certain time to the grammar and to the Latin tongue; a certain time to the arts, philosophy and to the tongues, and a certain time to that study in which they intend chiefly to travel for the profit of the commonwealth (quoted in O'Day 1982:223-4).

'There is nothing here of the right of every child to an elementary education', argues O'Day. 'Everything is related to the needs of the Church or, to a more limited extent, of the State' (O'Day 1982:223).

Dickson argues that 'The whole history of Scottish education is to be found in the endeavour to make this system as complete as possible' (Dickson 1921:1496); but O'Day suggests that the most remarkable feature of the proposal

was not that it contained a movement towards the principle of a universal right to education (which it certainly did not aver) but that it realised that, in order to harness the potential of the nation most efficiently to the Protestant cause, the system would have to be highly organised and controlled (O'Day 1982:224).

Besides setting out the content of the teaching at the three levels - primary, secondary and university - the scheme also provided for a system of ten superintendents to oversee the schools and colleges, and a system of examinations - commonly in the form of a certificate of suitability from a boy's minister or high-school master - to control progress from one level to another.

As to the implementation of the scheme, O'Day notes that 'During the remainder of the sixteenth century relatively little attention was paid to the foundation of schools', while the Kirk was 'too preoccupied with the need to establish reformed churches and ministers to make the planning of schools a priority' (O'Day 1982:226).

The General Assembly set up commissions to found new schools in Moray, Banff, Inverness and Ross in 1563 and 1571, and in Caithness and Sunderland in 1574. In 1565 John Row was commissioned to visit all the kirks and schools in Kyle, Carrick and Cunningham and to suspend inadequate teachers and ministers. A few parish schools were endowed by individuals.

But attempts to persuade the government to spend the proceeds of the dissolution of religious houses on education were unsuccessful, and in general, 'formal educational provision was neglected in late sixteenth-century Scotland' (O'Day 1982:226).

However, after the Reformation the burgh councils were able to provide education appropriate for an individual town's needs. Whereas in England the provision of schooling depended largely on individual endowments, in Scotland it was based on the efforts of the burgh councils and the New Kirk working together. But there were some similarities between the two countries, including much criticism of the traditional classical curriculum. 'Education was regarded in secular utilitarian terms' (O'Day 1982:237).

Conclusions

Whether the Reformation had a positive or negative effect on education in England has been a matter of debate for more than a century.

In his 1976 book Education in the West of England 1066-1548, Nicholas Orme argued that the favourable view of the Reformation which was widely held up to the end of the nineteenth century was 'based on the assumption that since there were few English schools in the middle ages, the foundations of Henry VIII and Edward VI must be considered a positive improvement' (Orme 1976:31).

But this assumption had been challenged in 1896 when, in his book English Schools at the Reformation, AF Leach had 'demonstrated the existence of a considerable number of medieval English schools' and emphasised 'the disorganisation of education under Edward VI, with the closure of elementary schools and the conversion of grammar school lands into fixed stipends which failed to keep their value' (Orme 1976:31).

The truth, Orme argued, probably lay halfway between these two judgements and 'it is difficult to ascribe either a significant expansion or recession of schooling to the Reformation alone' (Orme 1976:32).

In his later book Medieval Schools from Roman Britain to Renaissance England (2006), Orme suggested that

Leach underrated the injury caused to schools under Henry VIII, because of his poor regard for the education provided by monasteries. In turn he overestimated the adverse effects of the dissolution of chantries and guilds under Edward VI (Orme 2006:334).

Orme concluded that 'although some schools and localities suffered from royal policies, it is unlikely that there was any great recession of school education in mid sixteenth-century England' (Orme 2006:334).

The Tudor monarchs' involvement in schooling, he argued, 'arose not so much from a concern with education but because schools got caught up in [their] religious and financial policies' (Orme 2006:334). However, they were 'not altogether lacking in proactive educational policies, at least from about 1540' (Orme 2006:335). Henry imposed his authorised grammar; Edward provided for visitations of cathedral schools, required the bishops to supervise school statutes, and sought to involve parish clerks in teaching children. Under Mary teachers were licensed.

These initiatives

marked a departure from the later middle ages, when neither the Church nor the crown had involved itself with schools on a national scale. At the same time the development of policies for schools was slow and often limited, and teaching received far less attention from the authorities than other social issues of the day. If we add up all the Tudor statutes and proclamations relating to schools, the total is small compared with those about poverty, law and order, wages and prices, and even recreations (Orme 2006:335).

In his 1965 book Education in Renaissance England, Kenneth Charlton also argued that the effects of the Reformation on English education were mixed, describing the picture as 'curiously two-faced' (Charlton 1965:89):

On the one hand the Reformation enacted by Henry VIII and his son Edward VI has been described as being responsible for the crippling of school education in England by the dissolution of educational institutions based on monastic and other religious houses as well as on chantries and gilds. Yet on the other, the large number of grammar schools bearing the names of these sovereigns is cited to show that they were personally active in providing essential patronage for the spread of grammar school education (Charlton 1965:89).

Leach's analysis, Charlton argued, could be criticised on two counts: that 'many schools which came within the purview of the commissioners were in fact "continued" and improved, and that even then there was a parallel stream of lay foundations untouched by the chantry legislation'. And he 'grossly overstrained the evidence for the existence of particular grammar schools in the Middle Ages'. Leach also 'ignored the fact that the reformers themselves were passionately interested in education and well-recognized the value of schools in the propagating of their ideas' (Charlton 1965:93).

Far from 'crippling' schools, the Reformation 'put many of them on a more solid foundation by placing them in the hands of a middle class which provided the chief demand and had an interest in their survival' (Charlton 1965:94). It also produced a lay teaching profession, in which the teacher was no longer responsible for the religious observances of the chantry priest. However, while control over education was now secular, its aim was 'undoubtedly and increasingly more precisely religious' (Charlton 1965:94):

The accepted connexion in the minds of both Romans and Reformers between religion and education was made explicit in a variety of ways: by the statutory enactments of the Tudor sovereigns, the diocesan injunctions to parish vicars and curates, the episcopal licensing of teachers, and the detailed injunctions and prescriptions with which individual grammar schools were surrounded by their statutes and ordinances (Charlton 1965:94).

Religion, then, continued to be a powerful force in the provision of education in England after the Reformation. The difference was that that religion was now Protestant rather than Catholic.

References

Ascham R (1570) The Scholemaster ed. Judy Boss London: John Daye

Charlton K (1965) Education in Renaissance England London: Routledge and Kegan Paul

Chitty C (2007) Eugenics, race and intelligence in education London: Continuum

Dickson R (1921) 'Elementary education in Scotland' in Watson F (ed) (1921) The Encyclopaedia and Dictionary of Education 1496-1497 London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd

Goldschmitt EP (1950) The Printed Book of the Renaissance Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Lawson J and Silver H (1973) A Social History of Education in England London: Methuen & Co Ltd

Leach AF (1915) The Schools of Medieval England London: Methuen & Co. Ltd

O'Day R (1982) Education and Society 1500-1800 London: Longman

Orme N (1976) Education in the West of England 1066-1548 Exeter: University of Exeter

Orme N (2006) Medieval Schools from Roman Britain to Renaissance England New Haven: Yale University Press

Simon J (1966) Education and Society in Tudor England Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Watson F (1921) 'Sir Thomas Gresham (1519-1579)' in Watson F (ed) (1921) The Encyclopaedia and Dictionary of Education 756-757 London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd

Williams R (1961) The Long Revolution London: Chatto and Windus

Chapter 1 | Chapter 3