[page 81]

CHAPTER VIII

The Rest of our Lives

HISTORY is made by men. It is therefore natural that in its deepest sense it should be the proper study of men, not children. This is not to deny the value of history teaching in schools, with which this pamphlet has been mainly concerned. To the well-taught child, indeed, the study of history may have all the fascination and the charm of a glimpse into the adult world; and rare indeed is the child who, content with childish things, does not strive to enter the mysterious and still unattainable world of grown men and women. History is one of the many, and one of the most profitable ways by which he makes the attempt and grows in stature as he makes it. But as long as he remains a child, or while he is at any rate still less than a man, the adult world is ultimately beyond his reach. Just as his school days as a whole prepare him for the world of men, so do (or should) his school history lessons prepare him for that mature study of history which is only possible for those who are old enough to help to make history.

But if the study of history is fully possible only to adults, is it today a study which adults do in fact pursue? What provision is made for it? How far is this provision used? "Study" is a hard and serious undertaking and a good many of the ways in which we encounter history do not deserve this term. Although there are learned societies which exist to foster the study of history, and numerous courses of lectures and classes for adults in historical subjects, our perspective is the more accurate if we leave them to a later stage and think first about books, newspapers and periodicals, the wireless and the cinema and stage as principal means by which ordinary unorganised men and women are brought into contact with the world of history. These, of course, are general influences to which the whole community is subject. Children as well as adults read the newspapers, go to the cinema, buy or borrow books and so on; but they are produced by adults and usually for adults. Their use by children is secondary.

It is no bad thing to take stock for oneself of the volume and nature of the historical influences to which everybody is exposed. The following brief account of one such personal inquiry will have served its purpose if it encourages others to conduct their own exploration and draw their own conclusions. The purpose of the

[page 82]

inquiry was to gain a general impression of the extent to which history, historical study and stimulants to historical imagination are in evidence in England today. No doubt there is room for a carefully planned scientific investigation, but this was not one. It was no more than one lover of history keeping his eyes open with a particular purpose as he read his papers, walked the streets, browsed in bookshops and visited the public library.

Historical Reading

The first step was to consult the list of "Books Received" which is printed each week in The Times Literary Supplement. Ten consecutive issues were examined and showed that about one-fifth of the items listed might reasonably be regarded as history. More striking, perhaps, was the fact that less than half these books were in fact classified in the Literary Supplement's list under History. The majority were included under other headings such as archaeology, biography, education, science, religion or war. This was a useful reminder of how wide the ramifications of history are. There is no subject which is not capable of being treated historically; there are few, if any, subjects which are not better understood when their history is remembered. How was the figure of one-fifth arrived at? In the first place those books which the Supplement classified as history were accepted without further consideration. Next certain other categories were ruled out entirely on no better ground than a modest reluctance to claim too much as history. Thus books on the fine arts were excluded en bloc, though he would be but a poor historian, or art critic either for that matter, who would deny Leonardo da Vinci a place in history as well as in eternity. On the other hand, histories of architecture were included. Another rashly generous exclusion was the whole field of literary criticism and of reprints of the classics, although the historian of nineteenth-century England who forgot Keats would be as poor a craftsman as the literary critic who considered him without his context. No fiction, either, was included in the fifth share claimed for history, though a fair number of the novels were certainly historical.

But many of these books, of course, were works of specialist interest whose appeal to the general reader is necessarily small and of which, therefore, not many copies would be printed. What, in fact, is the impact, either direct or indirect, of historians on the man in the street? The next step, therefore, was to spend some time in the principal, and virtually the sole, bookshop in a typical country town of less than 9,000 inhabitants. In one window nearly a quarter of the books displayed were historical. Twenty-five of

[page 83]

them, it is true, were copies of Mr. Churchill's third volume on the second world war, but there were also works by Dr. G. M. Trevelyan and Mr. A. L. Rowse, as well as a standard history of New Zealand. In another window children's books were set out. Nearly one in ten was historical - mostly, but not exclusively, historical stories. In the entrance there was the familiar display of cheap paper books. There were nearly a hundred different titles - just over a quarter were historical subjects if one may stretch the definition wide enough to include Mr. Norman Douglas' Siren Land as well as such undoubted histories as the Hammonds' Bleak Age. Inside, one table was devoted to novels. There were some 150 different titles. It was reasonable to class twenty of them as books with a historical theme, setting or interest. There were Conan Doyle's historical romances and new books with settings as diverse as New Orleans in the 'sixties, the Wild West when the frontier was still open, Pembrokeshire in the time of Napoleon and Fermanagh in more recent days. The non-fiction table held just over a hundred different volumes of which over one-quarter were historical works. There was something on virtually every century of medieval and modern history. Many of the books were by distinguished historical writers - there were, for instance, works by Z. N. Brooke, Herbert Butterfield, J. H. Clapham, G. P. Gooch, E. Halevy, Douglas Jerrold and G. M. Trevelyan.

How much in fact do books by serious writers like these get read? One summer day in 1950 another small country town had on its public library shelves eleven such books which had been acquired during the previous year. They had been borrowed a total of sixty-seven times, three of them ten times each (Professor Toynbee's Civilisation on Trial, Miss Rickert's Chaucer's World, and Mr. J. G. Lockhart's Archbishop Lang). Other books, no doubt, were out on the day in question.

The centenary of public libraries was celebrated in 1950 by an exhibition at the National Book League. One of the exhibits was the display of 250 books actually acquired in one week by a Metropolitan borough library. Nearly a quarter could reasonably be classified as history. The most conspicuous features to a historian were the large groups of books on local history and topography, on art history in various forms and on matters of religious history.

Wireless and Press

Libraries and bookshops serve restricted areas and no doubt there are wide variations throughout England in the extent and the nature

[page 84]

of the historical books which they provide. It is otherwise with the B.B.C. programmes. In one summer week in 1950 there were nearly fifteen hours of historical broadcasting, of which nearly five were on the Home programme, two and a half on the Light, and the remainder on the Third. The topics treated included a nineteenth-century missionary in Tierra del Fuego, Bligh of the Bounty, colonists in western Canada, the field of Culloden and the changes wrought by science in the last 200 years.

There is one special use of wireless which ought not to be forgotten. It is the direct transmission, often with an invaluable commentary, of great national and international occasions. Who that heard them will ever forget the abdication speech of King Edward VIII, the coronation of King George VI or the marriage of Princess Elizabeth? Or, from a very different series, the relief with which Mr. Neville Chamberlain brought back "peace with honour" from Munich, the sad dignity of his words on September 9th a year later, the robust defiance of Mr. Winston Churchill after Dunkirk, the brilliance of Mr. Priestley's famous description of "the Little Ships", and, at the end of the story, the grim scene at Nuremberg as we actually heard the Nazi leaders being sentenced to death. Already television is beginning to enable us to see as well as to hear such events as they actually take place. In these ways ordinary men and women are enabled both to encounter history as it is being made and to enter more fully than ever before into the great and continuous historical heritage of English life by taking part in those ceremonies which come down from the past, incorporating, explaining and perpetuating it while enriching the present.

High among the historical influences which surround us must be placed the daily newspapers. It is for the time being not quite so easy to appreciate this as it used to be in England and as it still is in lands where there is plenty of newsprint. For this reason it is well to look at the papers of pre-war years if one wishes to see what newspapers can do and, it is to be hoped, will do again to make and keep Englishmen conscious of their heritage. The point can well be made by looking at a volume called Reporter which contains some of the most characteristic articles of Francis Perrot of the Manchester Guardian. They not only contain a vivid and precise description of what he saw, which is rich source material for the historian, but also the historical memories provoked in him by what he saw, which was historical education for his readers. Consider this extract from his story of Florence Nightingale's funeral in 1910:

As the body was borne into the church there was sitting in the porch a little

[page 85]

old man in decent black, wearing pinned on his waistcoat the Crimea medal with the Sebastopol clasp. Once he was Private Kneller, of the 23rd Foot, now old Mr. Kneller, the Crimean veteran of Romsey. If you talked to this cheerful old veteran he would readily tell you how in the trenches before Sebastopol he was shot in the eye and was taken to the hospital at Scutari - how as he lay in the ward there night by night he would see a tall lady going along past the beds carrying a lamp. He does not remember at all whether she ever spoke to him, nor whether he spoke to her, but he remembers like a spark in the embers of his dwindling mind the apparition of the lady who came softly along the beds at night carrying in her hand a lantern - "one of them old-fashioned lanterns."

Has the story ever been better told?

Film and Stage

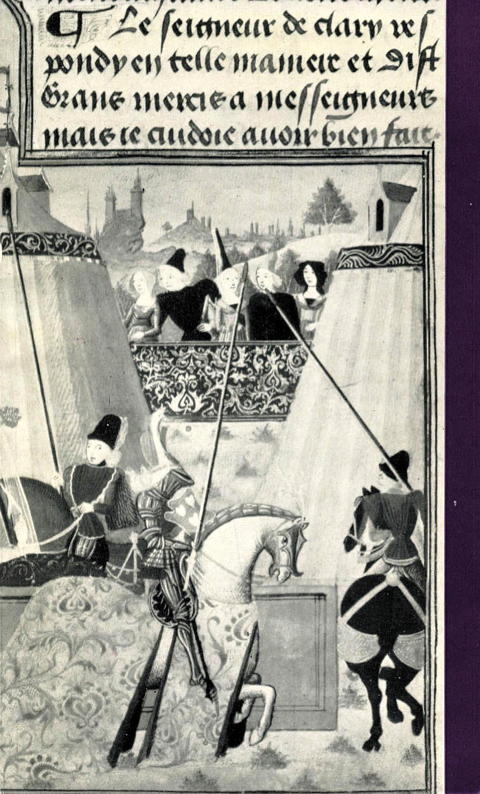

What they see produces at least as strong an impression on most people as what they read. Great, then, must be the effect which plays and films have on the historical ideas of our generation. Historical subjects, too, have an irresistible fascination for producers because of the opportunities for spectacular display which they provide. From The Birth of a Nation to The Mudlark, from Ben Hur to Samson and Delilah (a more characteristic progress), many hundreds of films have impressed some true history and much false on many millions of people. "The Frontier" in American history is a conception with which perhaps a few thousand Englishmen are consciously familiar; in pictorial form it is part of the dream world of almost every boy in London. The most important effect of the films on the ordinary man's historical consciousness is, perhaps, the establishment of certain fixed ideas, usually of a social nature, made by the constant recurrence of films dealing with certain themes - the brutality of life on sailing ships, for instance, or the masculinity of the Wild West, or the gay and wicked life of Gold Rush towns. These impressions are driven home with sledge-hammer blows month after month on nearly all those who have a regular habit of cinema going. They are bound to be stronger than the individual impression of particular people or incidents left by a single film seen once only.

There is little doubt that it is worth paying attention to forming at school a discriminating judgment about the cinema. After all it is while we are still young that we first encounter the stock scenes and characters of the curiously small but vivid world of film history which we shall apparently revisit at frequent intervals throughout our lives. It is on our first acquaintance that we can best learn to know them for what they are, and the real thing for what it was.

Compared with the cinema the influence of the stage is severely restricted. On the whole those who go to the theatre are rather better educated and go in a more discerning frame of mind than

[page 86]

those who go only to the cinema. On the whole, too, the historical fare put before them is more varied than the few stock themes of the cinema, so that we have to deal with a series of individual impressions rather than with the creation of potent myths. The only approach on the stage to the persistence of the Western among films is the Ruritania of musical comedies. To assess the historical influence of the modern stage would involve considering a whole series of plays as various as Murder in the Cathedral, Cavalcade, The First Gentleman, St. Joan, The Barretts of Wimpole Street, The Lady's not for Burning, The Plough and the Stars and Richard of Bordeaux. Such a task would be far beyond the purpose of this chapter.

Historical Sight-seeing

The historical influences which we have been discussing up to this point have this in common: they are under no local or temporal restriction of subject matter. Books, plays, films, radio programmes and newspapers can deal with equal facility with ancient Athens or modern Basutoland although their authors may never leave London, nor their readers or audiences the West Riding or Wiltshire. But if a man wants to see Westminster Abbey for himself he must go to London; Hadrian's Wall can only exert its full hold on a man's imagination if he takes the trouble to visit it. And, once there, the historical influences which overwhelm him - that is, if he is sensitive at all to the spell of place and time - are solely those proper to that setting. At Westminster his thoughts will turn to the medieval English kingship; at Housesteads to the problems of an outlying Roman province. Our country is still rich, perhaps beyond all other lands save Italy, in the probability of meeting at almost every turn a still living past. In one sense it is richer now than ever before. The ordinary traveller and holiday maker has long had open to him all the surviving glories of the medieval church and most of the military remains of the Middle Ages. He has had until very recently to be content with an outside view of the great country houses whose owners made so much of England as we know it. Today taxation is destroying that private life of public men which was long lived in them, but in consequence it is opening to thousands of holiday makers many doors which once were closed. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries will now be able to make that imaginative appeal by direct personal contact which used to be almost reserved for the Middle Ages. English history must often have seemed to the sightseer to stop with the dissolution of the monasteries. It need do so no more.

The country bookseller's shop, to which reference has already been

[page 87]

made, had a display table devoted to maps and guide books. It was probably a mistake not to have examined the contents of that table with the same care that was devoted to the novels and the general non-fiction books. How far the sightseer understands the historical monuments he visits depends in large measure on the quality of the information he is given at the time of his visit by guides, guide books or notice boards. Naturally these differ widely in value and there must be many exceptions to any general comments which can be made. There are, however, two points which seem worth special consideration from a historical standpoint.

The first is the change which has taken place in the present generation in the arrangements for visiting most English cathedrals. It is now usual for visitors to be allowed to go without charge wherever they like and to rely for their information either on printed guide books or on notices displayed at particular points of interest. This is just what the visitor with a good general education wants; but the almost completely ignorant visitors, who may well form the majority, have probably lost something which was given by the Verger's tale, at least when it was skilfully, dramatically and humorously told.

The second point is that almost all guides and guide books are concerned with the particular to the exclusion of the general. They assume a general background knowledge which commonly does not exist, and concentrate on the special features of the place with which they are dealing. How many of the visitors to Rochester Castle, to the Rows of Chester, to Fountains Abbey or to Blenheim Palace have the knowledge to picture at all fully or accurately the life that was once lived in them? Yet, in terms of the three main types and aims of history teaching distinguished in Chapter I it is perhaps to the "patch" approach with its insistence on "getting under the skin" of another period that historical sight-seeing has the greatest contribution to make. It may well be that one of the most useful pieces of work waiting for historians to do is the careful consideration of how best use can be made of the opportunities for historical education which sight-seeing presents.

Much, perhaps most, of this education through sight-seeing will have to concern itself with the chance, casual contact which the holiday maker enjoys. But much can also be done by teaching in schools to prepare a more continuous and conscious interest among adults. Something has already been said in Chapter V about the fascinating material which the parish church provides for use in historical education. Boys and girls who have been brought up in this way are already more than half-trained recruits for the

[page 88]

archaeological, antiquarian and historical societies in which England is rich, and which, perhaps increasingly, undertake valuable research work. The use of local records in schools, which was also discussed in Chapter V, will, as it becomes more common, make people anxious to join such learned societies because they already know what excitement for the mind they have to offer. Sometimes, too, these societies offer exercise for the body as well. They undertake or support the excavations which yearly increase our knowledge of the past. Some people are fortunate while still at school to be apprenticed to this work, but for the most part it is inevitably an adult study.

In all these ways education at school can help to make men aware of our local historical heritage and of how they can help to extend and deepen our knowledge of it. But history is more than local history, and the keenest antiquarian will need opportunities to discuss matters of more than or of no local significance. The school library which subscribes to History or History Today may be the means of introducing new members to the Historical Association, whose branches provide in many places just such a fruitful meeting place for those who want to keep abreast of our general knowledge of the past. Many of its members, naturally, are teachers of history, but there have always been plenty who have no professional concern with history. Their value to the Association is great.

History in Adult Education

The local newspaper and the local library are probably the main methods by which newcomers are brought into contact with the activities of these voluntary societies. They are also among the best means by which the provision for formal adult historical education is made known. Some of these classes may be organised directly by a university extra-mural department, some by the Workers' Educational Association, some by the two in conjunction or by other grant-earning "responsible bodies". It is likely that some of these classes will be in historical subjects. Throughout the country, the number of students in adult classes more than trebled between 1931-32 and 1950-51, rising from 46,757 to 162,850. In the same period the number of classes more than trebled. The proportion of students in "pure" history classes in the last available year was about one-eighth of the total. There are no figures available to show how many students were studying historical subjects in either year, but the number of classes in different subjects is known. It seems reasonable to group together as "history" those classes listed as general history, economic history, political and

[page 89]

social science, current affairs, international relations and "religious history and literature". On this basis the average number of history classes in the three years ending 1931-32 was about a fifth of the total number of classes. For the three years ended 1950-51 the proportion had risen to about a third. It is obvious, too, that many of the literature and drama classes (507 in the first period and 798 in the second) were also incidentally classes in history. On the whole it is true to say that most townsmen live within reach of some evening class in some historical subject, and that all may do so, and enjoy generous support from public funds in the process, if only they are keen enough to collect a few like-minded friends.

Impressions can sometimes speak more eloquently and more penetratingly than figures, and perhaps the best way to understand the significance of history in adult education is to make the acquaintance of some of those who are studying it.

Miss A. is a clerk approaching middle age. She is also a specialist in maritime history who has done some extremely careful work on the records of a shipping firm engaged in the slave trade.

Mr. B. is a young locomotive fireman who has been attending tutorial classes for nine years. The classes have been in a succession of different subjects so that he has acquired a fairly liberal education in his spare time. He, too, has undertaken original work - on the eighteenth century poor law records of his town. His interests in the past run parallel with a lively and thoughtful concern for social problems of the present.

Miss C. is a young woman who lives in a remote village whose Literary and Debating Society has developed into a tutorial class in English literature. She has also acquired a good deal of knowledge of other aspects of English history through reading the village schoolmaster's books - Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations among them.

Mr. D. is an energetic man of middle age, a miner with a passionate concern for the welfare of his fellow miners. For twenty years he has been a diligent member of tutorial classes and other W.E.A. activities, gaining an extensive knowledge of many topics and a near-scholarly mastery of the history of mining.

To meet students like these is to understand why it is that they are able to command the services of tutors who are often men of academic distinction and who may be, like Professor R. H. Tawney, among the foremost historians of the day.

An Adult Study

Most men would admit that part of the delight they feel in history comes from the satisfaction of the desire for romance, and especially

[page 90]

the desire for true romance. Without these flavourings history would be but a poor and little relished diet for the mind; but unless it has a good deal more substance, history has no right to a high rank in the mental diet of adults. Men and women to whom history is more than an incidental influence usually approach its study with one or both of two further aims in view. They read it because they are filled with a desire to understand the present, or because they have a desire to move among things more lasting than the present, the most mutable thing in the world.

Men and women who have come to this point in their study have found for themselves the values which were indicated earlier in this pamphlet in the discussion on the purpose of history teaching. The sad thing is that very often they have come to it apparently unhelped by what they have been taught in school or even, at least in their own conviction, in spite of it. A skilful tutor had nursed a group of very ordinary people in an industrial London suburb through three years of continuous historical study. The first year had had to be disguised as a one-year "sessional class" in "modern social problems" in order to attract an audience. At first its members resisted any suggestion that they should go on to study history, although week by week they found themselves plunging into the past in order to understand the present. Eventually they agreed to continue in a three-year tutorial class with a study of social history in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The following year they embarked on a study of the constitution in the same period and found themselves thoroughly enjoying Bagehot. For their fourth year (the third of the tutorial class) they decided after keen debate to study political theory in the same two centuries rather than yield to the softer option of European history. When visited, the little group of eleven, all of whom had followed the whole course, had just finished a month on Hobbes and Locke and were beginning on Hume. One keen member of the class, a sheet-metal worker and local councillor, was forthright in his judgment: "I used to hate history at school," he said, and the others backed him up with "but that was all dates" - the framework without the content or experience to give it meaning. Leaving school when he did, the sheet-metal worker could not, indeed, have been given the awareness of what history really is which he is now discovering, but he might have enjoyed a preparatory experience. Indeed, historical awareness can hardly arise without wide previous acquaintance with historical material, which can and should be put in hand from an early age.

This birth of true historical understanding is, perhaps, nowhere

[page 91]

better described than in Mr. Howard Spring's Heaven Lies About Us.* He had won as an evening class prize Taine's History of English Literature.

Till then [he writes] what with the books my father instilled into my mind, what with the rich and heterogeneous mass Frank's brother had left behind him, and what with the vast and unrelated forays I had here and there made on my own account: what with all these things, English literature was for me a glorious, coloured jig-saw, not yet composed. And, reading Taine, I saw all the bits and pieces shuffling to their places; I saw new and unguessed bits moving into the pattern; I saw at last not a welter but a design, the rich and royal road of letters, marching from the rugged cell of Baeda to the fertile and watered meadows of Tennyson's England. And that, too, was one of the grand and unforgettable adventures of the spirit, such as might come to a watcher of the skies not when some new planet swims into his ken but when there breaks an apprehension of the rich and ordered harmony in which all the planets swing together about their celestial business.

*Constable, 1948.

Teaching for

International Understanding

by

G. F. STRONG, O.B.E., M.A., Ph.D.

This is a statement prepared for the Standing Committee on Methods and Materials of the United Kingdom Commission for UNESCO, and published under the auspices of the Ministry of Education. The statement represents the work of the Standing Committee in evaluating the available material relating to the international interests, obligations and potentialities of education in the task of fostering a world society, of collecting what further evidence it thought necessary, and of making recommendations for practical action which would be of real assistance to teachers and pupils.

3s. 6d. By post 3s. 11d.

OBTAlNABLE FROM

HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE

at the addresses given on page 96

or through any bookseller

OTHER PAMPHLETS IN THIS SERIES

No. 3. Youth's Opportunity: Further Education in County Colleges (1945). 3s. 6d. (3s. 10d.)

No. 8. Further Education: The Scope and Content of its Opportunities under the 1944 Act (1947). 6s. (6s. 7d.)

No. 14. Story of a School: A Headmaster's Experiences with Children Aged Seven to Eleven (1949). 2s. (2s. 4d.)

No. 16. Citizens Growing Up: At Home, in School and After (1949). 2s. 6d. (2s. 10d.)

No. 19. The Road to the Sixth Form: Some Suggestions on the Curriculum of the Grammar School (1951). 1s. 3d. (1s. 7d.)

No. 21. The School Library. (1952). 2s. (2s. 4d.)

No. 22. Metalwork in Secondary Schools. (1952). 5s. 6d. (5s. 10d.)

No. 24. Physical Education in the Primary School: Part I, Moving and Growing (1952). 7s. 6d. (8s. 5d.)

No. 25. Physical Education in the Primary School: Part II, Planning the Programme (1953). 6s. (6s. 11d.)

No. 26. Language: Some Suggestions for Teachers of English and Others (1954). 3s. 6d. (4s.)

No. 27. Music in Schools (1956). 2s. (2s. 4d.)

No. 28. Evening Institutes (1956). 3s. (3s. 4d.)

No. 29. Modern Languages (1956). 3s. (3s. 5d.)

No. 30. Education of the Handicapped Pupil, 1945-1955 (1956). 2s. ( 2s. 4d.)

No. 31. Health Education (1956). 5s. (5s. 7d.)

No. 32. Standards of Reading, 1948-1956 (1957). 2s. 6d. (2s. 10d.)

No. 33. Story of Post War School Building (1952). 3s. 6d. (3s. 11d.)

No. 34. Training of Teachers: Suggestions for a Three Year Training College Course (1957). 1s. 9d. (1s. 11d.)

No. 35. Schools and the Countryside (1958). 5s. 6d. (5s. 11d.)

No. 36. Teaching Mathematics in Secondary Schools (1958). 6s. (6s. 6d.)

No. 37. Suggestions for the Teaching of Classics (1959). 4s. 6d. (4s. 10d.)

No. 38. Science in Secondary Schools (1959). 6s. (6s. 6d.)

Primary Education: Suggestions for the consideration of teachers and others concerned with the work of Primary Schools (1959). 10s. (10s. 11d.)

Prices in brackets include postage

OBTAINABLE FROM HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE AT THE ADDRESSES ON PAGE 96.

[page 96]

© Crown copyright 1960

Published by

HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE

To be purchased from

York House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2

423 Oxford Street, London, W.1

13A Castle Street, Edinburgh 2

109 St. Mary Street, Cardiff

39 King Street, Manchester 2

50 Fairfax Street, Bristol 1

2 Edmund Street, Birmingham 3

80 Chichester Street, Belfast 1

or through any bookseller

Price 5s. 0d. net

[inside back cover]

[back cover]