[page 16]

CHAPTER IV

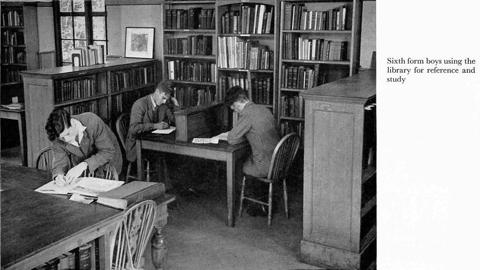

REFERENCE, STUDY AND RECREATIVE READING

BOOKS are used in school for three purposes, namely, to obtain information, to build up a body of organised knowledge, and to enjoy an imaginative experience. We usually call the activities involved reference, study and recreative reading. The activities often overlap and the purposes are indistinguishable - study involves reference, and recreative reading often results in both information and knowledge - but the three divisions form convenient headings for certain considerations relevant to the theme of this pamphlet.

REFERENCE

Reference, that is, the consultation of authorities, is the basis of study, and to feel the necessity of knowing the facts, to have established the habit of searching for them and to have acquired the skill to find them, is to have gone far towards becoming a student. The term 'reference books' is sometimes loosely used to cover almost everything that is not classed as fiction. Any book that contains required information may, of course, be used for the purpose of reference, but, properly speaking, reference books are books compiled and arranged with the object of making it easy to look up items of knowledge. At one extreme they are the apparatus of advanced study, at the other the student's first box of tools. If suitably designed and written, they can be used as soon as children are able to read and understand them. And there is a great deal to be said for making as early and as full use of them as possible. Even at the level of mere fact-finding, and short of a real process of study, the practice of reference has great educational values.

The day of the polymath and the infant prodigy is over.

And still they gaz'd, and still the wonder grew,

That one small head could carry all he knew'

says Goldsmith of his schoolmaster, adding prophetically, it seems,

'But past is all his fame'.

The dangers of a too well-informed schoolmaster were

[text continues after photographs]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 17]

recognised long ago. Quintilian mentions a certain Didymus ('than whom nobody wrote more') and comments, 'Amongst the virtues of a good schoolmaster I should include a little ignorance'. That a schoolmaster should himself be a humble fellow-inquirer rather than a symbol of omniscience is not merely the notion of an age in which dictators are unfashionable. More important than the inculcation of any fact is the instilling of a respect, indeed of a fundamental reverence, for truth, and in no way will this attitude be so effectively conveyed as by the schoolmaster's own example. When the class does not know something the teacher recognises the situation as one of opportunity. But when the teacher himself does not know something and the class knows that he does not know - what, with twenty, thirty, forty pairs of eyes upon him, does he do? We are all familiar with this 'crisis' and most teachers achieve some technique of meeting it with the minimum disturbance to the lesson. But may opportunities not be lost which might more than compensate for disturbing the best of lessons? 'Nor', says J. H. Fowler, in his pamphlet, School Libraries, 'should teachers forget the value of a good example. There ought to be no doubt in the pupils' minds that the master cares for books for their own sake and is not afraid of taking trouble to clear up a doubtful point by research' (1).

Further, our idea of the well-informed pupil is changing somewhat. There is now so much to know that we doubt the wisdom of his trying to carry it in his head; and we suspect that if he tries too hard he will be more occupied with remembering than with thinking. A distinction is necessary here. There is a knowledge of principles derived from the accumulated experience of our civilisation and embodied in its religion, ethics and rudiments of learning. There can be no question of leaving the pupils in any doubt about this kind of knowledge, since it will determine their conduct, usefulness and happiness. But there is a lot of information not unlike the lists of capes, bays, rivers, lakes and mountains memorised by our grandparents that can more profitably be left to be looked up when the need for it arises - provided the pupil has learnt the trick of finding it. The older ideal was Browning's Grammarian:

Grant I have mastered learning's crabbed text,

Still there's the comment.

Let me know all!

Now we realise that knowledge has grown beyond the ability of any human mind to contain it and that the conditions of life are changing so rapidly as to make it increasingly difficult to know what information beyond the staple minimum is likely to be of most value to children

(1) English Association Pamphlet No. 33. (1915.)

[page 18]

of the next generation. 'In the past the timespan of important change was considerably longer than that of a single human life', says Whitehead (1). 'Today this timespan is considerably shorter than that of human life, and accordingly our training must prepare individuals to face a novelty of conditions.' What is of most value in confronting a new situation is a readiness to discover what the real facts of it are. How can we encourage that readiness?

Many schools already give their pupils some training in the manipulation of reference books. Exercises have even been designed and published to facilitate their task. But the good teacher knows that no lesson is as effective as that which grows out of a natural situation, and the daily routine of school life, both inside the classroom and out, is continually providing occasions when the need for knowledge makes itself obvious. Whatever is a subject of instruction, of private interest, of conversation or dispute, creates a demand for information, verification, precise knowledge. Three kinds of occasion will suggest themselves at once, and it is worth while pausing over each to realise the opportunity it offers.

First, there are the occasions implicit in our whole approach to formal teaching. Nature's kindest gift to the teacher is a child's spontaneous inquisitiveness. The kindest return a teacher can make to a child is not the sad satiety of having questions answered before they are asked, but the strengthening of that inquisitiveness into a permanent disposition. When thinking about a lesson beforehand, might not teachers stop more often to ask themselves how much of this they really need to tell the pupils? The contribution the teachers can most profitably make lies in discussing the significance of the facts - something the pupils have insufficient experience to do alone. Discovering the facts is their contribution - did they not learn to read and should they not be given as much opportunity as possible to practise their skill in that art? Besides, fact-finding is an enjoyable exercise, much resorted to in competitions; why deprive them of it? There is enough still to do in evaluating the importance of the facts in relation to the topic or problem in hand.

Second, the work of the classroom is only one side of a pupil's life and perhaps not always the most important. Some valuable lessons can continue elsewhere. The information the teachers are inclined to think most necessary is that called history, geography, science and so forth; but the facts the pupils themselves may be conscious of needing are more probably in the realms of aeronautics, ballet, dress fashions or camping-sites. If the library books are well chosen and kept up to date,

(1) A. N. Whitehead. Adventures of Ideas. (Cambridge University Press, 1933.)

[page 19]

the training in reference that is given in connection with subjects of the timetable will project itself into other fields where practice will be none the less valuable for being spontaneous.

Third, there are the incalculable opportunities thrown up daily in the exchanges of the classroom and in the conversation, arguments and disputes outside it. We should all admit that a teacher's first task, more important than imparting any specific information, is to teach his pupils to distinguish truth from falsehood and to revere the truth. We should also agree that it is his duty to establish in their minds the habit of ascertaining the exact truth whenever possible. But he has to go further; he has to make them realise as clearly as they can the difference between fact, conjecture and opinion. Disagreement in the fields of conjecture and opinion is legitimate and must be accepted with tolerance. It is not the least of attainments to have realised that there is a realm of ascertainable fact in which opinion and conjecture are out of place, and to have acquired in that realm the habit of scholarly exactitude is to have progressed far towards intellectual integrity.

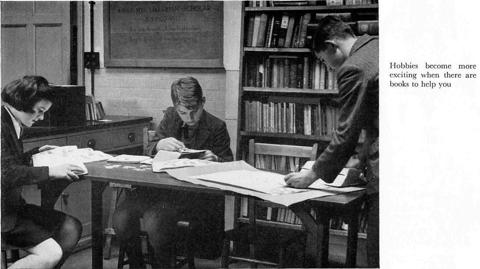

STUDY

'Studies serve for delight', said Francis Bacon, and it is significant that in their hobbies boys and girls first achieve the degree of mental application that can be called study. There, in complete absorption, purpose, industry and pleasure are completely fused. Is it fantastic to conceive of school as a continuous, expanding opportunity for such experience of delight in study? It may be objected that learning sooner or later demands hard and prolonged effort. Assuredly it does; but the passionate stamp collector, uncanny naturalist, and expert model engineer have already given proof of their capacity for this. Why should they not graduate by a natural progression into the scholars, administrators and craftsmen we would have them become?

The question is perhaps greeted with a shake of the head. An answer, it may be pointed out, was given long ago: 'I wolde fayne be a great clerke but I love not to studye.' But might it not depend on what is meant by study? Undoubtedly a time comes when most boys and girls grow tired of being taught. We ourselves would confess, much as we may enjoy learning, to being in some degree allergic to instruction. It is not unreasonable to suppose that a dislike of being taught may sometimes be a sign of growth; the maturing mind is, in fact, demanding a larger share of responsibility in the business of learning. Study of the kind made possible by a school library invites a different response from that associated with class teaching; it is a challenge. A pupil, set to study a topic,

[page 20]

however much help and guidance he may receive in formulating the questions it involves, in finding the authorities to consult and in weighing the answers, feels that he is in charge; the job is his. This alters the relationship of teacher and pupil from that of instructor and instructed to that of master and apprentice. What the apprentice achieves is not a copy of a set model but a work of his own, however many tricks of the master he may have borrowed in constructing it; he is on the road to producing his 'masterpiece'.

It would be manifestly unreasonable to suggest that study in this sense can take the place of teaching. The two are complementary. But study is the partner more liable to be neglected. Most of us are ready to admit that one of the chief aims of a school should be to produce efficient and self-reliant students, capable of continuing their own studies when they leave school, but sometimes, like St. Paul, the good that we would we do not. There are plenty of reasons, some of them, such as the requirements of examinations, only too convincing, for postponing the practice. It is often thought of as a special feature called 'private study' appropriate to the sixth form of a grammar school and too often there assumed to be something that comes naturally. The section on this topic in the Board of Education Educational Pamphlet No. 114 (The Organisation and Curriculum of Sixth Forms in Secondary Schools) (1) deserves careful attention, particularly the following passage:

'There is a tendency on the part of teachers to underestimate the special difficulties which confront a pupil in starting upon this kind of work. A boy who has never been brought to treat a book as a whole of inter-related parts with a centre or core of meaning, who has had little or no practice in handling an index or a table of contents or a catalogue, who has not begun to learn to find his way about an encyclopaedia - in a word, who has not even the most elementary conception of the use of a library, has much spade work to do before he can attempt anything which deserves the name of private study.'

Who should be set to study? Only those destined for the sixth form of a grammar school? At what age should they begin, and what kind of study should it be? Let us take the last question first. Two observations are perhaps worth making. There are few pupils who in their heart of hearts would not 'fayne be a great clerke', and a good teacher will often encourage each of his pupils to pursue some topic in which he or she has chanced to show an interest - trains, houses, aeroplanes, horses, Roman camps, Jacobean furniture, costume, beetles - and to

(1) H.M.S.O. (1938.)

[page 21]

become in that line at least the acknowledged expert who will be referred to whenever occasion arises or can be made to arise. Many a dull boy or girl has surprised both teacher and fellows by his or her response to such an opportunity for winning respect. That is the first point. The second is that throughout their school career boys and girls are required to do a number of exercises in oral and written composition, giving talks, making speeches, writing essays, in which form suffers through lack of content. At its worst the practice, devised with the best intentions, can even become an incitement to the hasty and ill-considered presentation of worthless opinions, not only a discourtesy to the listener or reader but a training in glib rhetoric and the vice of concealed ignorance. This danger has led more cautious teachers to place a good deal of emphasis on the stage of preparation for such exercises. For some exercises the use of reference books to verify factual details may be all that is desirable; others may require a well-informed and judicious treatment that involves the study of authorities. Many schools deliberately give their pupils the task of producing extended essays or theses that involve the reading of several books and may occupy the better part of a term.

These are general observations. Provided that pupils receive in one way or another their training in the use of books as the tools of study, the method of teaching in any individual subject is irrelevant to our purpose. Some teachers frame their scheme of work on a 'project' principle, some build it around 'centres of interest', some organise it in assignments on 'Dalton' lines, some follow an ordinary syllabus and vary their lessons with 'library periods' during which the pupils read up individual topics or do a piece of co-operative 'research'; many follow well-tried classroom methods but succeed by their scholarly influence in arousing an interest in the literature of their subject that makes the relevant section of the library a popular one.

An answer to the question at what age pupils should begin to study for themselves is already implied in the preceding paragraphs. If they are to get as much benefit as possible out of their work in the senior forms and leave school with the maximum skill and confidence as students, the sooner they begin the more gradual and the more thorough their training can be. Exactly when it should be is a matter for the teacher to decide in the light of the pupils' capabilities. Experience suggests that he is more likely to err in starting too late than too soon.

Finally, who should be set to study? The answer will be more evident if we phrase the question in another way: how dull must a pupil be to have no claim to the privilege of learning the use of books? There is still a doubt in some teachers' minds about the usefulness of a library

[page 22]

for pupils who are backward or markedly practical in their bent. But a school library can be built up for these also. Backward pupils need simple but not childish books; practical pupils need books on practical themes. There is here a point of general relevance. Study is not to be thought of as wholly a matter of book-learning or dismissed as something pertaining to the 'bookish' pupil. It has already been suggested that study often begins with a hobby, that is to say, a practical interest. And whatever it may become in advanced spheres of scholarship, study at the school level should always retain a basis of practical experience. For the younger or the less academically gifted this basis will need to be broader. The association of books with their interests and activities, whatever they are, will need to be closer. Study for some pupils may well mean the search for instructions and specifications, the consultation of handbooks or personal records in order to solve a practical problem in gardening, housecraft, woodwork or any other craft. The following passage from the Ministry's pamphlet entitled Reading Ability (1) is of special significance :

'It is easy for practical work to degenerate into the rote following of oral instructions; but, again with care, it can be so associated with reading that some real thought is involved, even for very dull pupils. The thinking is likely to be essential to the doing of the actual work, and it should not be lightly assumed that, because a pupil has difficulty in giving a coherent explanation of his experience, nothing has been added to his stock of learning.'

Admittedly we have not solved the problem with which we began. To say or even think we had would be to expose ourselves to the derision of those who come after us. But it is conceivable that the best solution our generation has to offer lies along these lines. Pleasure and industry need the flux of purpose before they can fuse; and much ingenuity is spent in awakening motives and appealing to interests. One thing a pupil is interested in is making progress; another is doing things himself. If teachers can turn more of their teaching into work that a pupil can undertake independently with skill and confidence, they may have gone some way towards creating that elusive sense of purpose.

RECREATlVE READlNG

Recreative reading no longer implies a concession to childish weakness but a recognition of the fact that children have a life of their own with needs that must find healthy satisfaction. Teachers, who well understand the significance of children's play, are unlikely to

(1) Pamphlet No. 18, Reading Ability: some suggestions for helping the backward. (H.M.S.O., 1951.) Out of print.

[page 23]

underestimate the importance of the recreative side of a school library. Doubts are sometimes voiced by others not immediately engaged in training children about the propriety of expending educational funds on works of fiction, especially if a public library is accessible out of school hours. The answer is that fiction of the right kind has a place of vital importance in children's development and while the teacher is glad to have every possible help from sources outside the school he cannot delegate to them an educational responsibility. He is concerned to turn his pupils into good readers; for that purpose he must have as his instrument a library in which the books are deliberately selected and include every kind of book that he believes will further his efforts.

Fiction is not, of course, the only form of recreative reading to be provided. Periodicals and books about hobbies, sports and games can equally be classed as such. But fiction is a main field of imaginative literature and the school cannot afford to neglect it. Moreover, no collection of books is representative of human interests if it omits so important a sphere of the creative mind. And, finally, fiction is indeed the kind of literature that has the strongest appeal to most children at certain ages and is therefore the most effective means both of establishing the habit of reading and of influencing taste.

Most readers of these pages will have already given much thought to the significance of children's reading. Not only the psychologists but the poets, as readers of Wordsworth's Prelude will recall, have emphasised the profound effect on the growing mind of those excursions into the realms of imagination that bridge the gap between the worlds of children and adults. Fortunate are those whose early reading gives them, as Wordsworth's gave him, a gracious introduction to life:

'Hence came a spirit hallowing what I saw

With decoration and ideal grace'.

The subject has been admirably dealt with in a number of books on children's reading which most teachers will know and every school librarian, it is to be hoped, will occasionally re-read. But two aspects are of such importance as to deserve at least a passing reminder. First, that in their imaginative reading boys and girls are actively forming conceptions of life and standards of conduct that may have a determining effect upon their career, happiness and worth to the world. With the right books and judicious guidance those conceptions and standards will modify themselves in the natural course of growth into the outlook of a mature and civilised adult. With the wrong books and advice, or with no books or advice, that development may be halved or distorted with terrible consequences. Second, at a later stage, the most

[page 24]

important educational influence is often an imaginative spark coinciding with a moment of heightened receptivity that is beyond the teacher's control. A letter of T. E. Lawrence describes such an experience on discovering a new field of reading, and comments:

'If you can get the right book at the right time you taste joys - not only bodily, physical, but spiritual also, which pass one out above and beyond one's miserable self, as it were through a huge air, following the light of another man's thought. And you can never be quite the old self again. You have forgotten a little bit: or rather pushed it out with a little of the inspiration of what is immortal in someone who has gone before you' (1).

Books, it is true, are only one of the formative influences acting upon a young mind, just as a school is only one of the sources of such influences. Many teachers take both facts into account and seek alliance with other agencies in a child's environment - home, church, public library, wireless and cinema. The school library can often be a useful meeting-ground for wholesome influences. Two examples that will occur at once are the prompt provision of the 'book of the film' and the book of the radio programme; another is the contact often made with the home through the interest a parent expresses in a pupil's reading. And here is a field where the school librarian and the librarian of the public library in his district should be in close personal touch. Each has his distinctive part to play, but they share the common task of creating a well-read nation, and ignorance of each other's efforts is an obstacle to the success of either.

The school setting out to produce good readers has two tasks before it: first, to create in as many pupils as possible the reading habit and, second, to raise their taste to the highest level of which they are individually capable. Success in creating the habit depends upon such factors as the example of the staff in showing a genuine interest in books, an adequate supply of attractive books, and plenty of time and opportunity to enjoy them. Nothing further need be said about the staff's part; it has been placed in its right order of importance - first. That the books should be available and attractive has been the constant theme of this pamphlet; but there is a practical question to be answered here. At what level should a pupil be allowed to read? There seems only one answer, that of Doctor Johnson: 'I would let him at first read any English book which happens to engage his attention.' A resourceful teacher will not find it necessary to dally long on the doorstep - or in the backyard - of literature. The question of the time and opportunity to enjoy the

(1) Letters of T. E. Lawrence, ed. David Garnett. (Cape, 1938.)

[text continues after photographs]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 25]

books is part of the problem of school organisation. Some schools give their pupils, as has been mentioned, periods for silent reading or browsing within the timetable; some encourage the pupils to keep books in their desks and bring them out whenever they have a moment to spare after finishing an exercise; some provide an opportunity during the midday interval or after lessons; some give no opportunity at all for leisure reading in school; most of them allow books to be borrowed from the school shelves for reading at home.

To improve taste in reading calls for a high degree of skill and devotion. The essence of leisure reading is spontaneity, the desire to read. If confidence in the pleasure to be gained from it is once lost, the habit of reading will collapse. It behoves the librarian therefore to advance warily, to know his pupil and his books thoroughly, and if he makes a mistake to correct it quickly. He is aware, of course, of the effort he and his colleagues are making to increase the pupil's power of understanding and appreciation in the lessons in English and other subjects, but he cannot presume upon this. He must watch each individual's changing moods and interests, supply their demand as far as he can and wait upon occasion. What level of taste can he ultimately hope to inspire? On the one hand, children differ in their reading ability, in the pace of their mental development, in the age at which they leave school. These are factors outside our control. On the other hand, how many of them have had the privilege of passing through infancy, childhood and adolescence in continuous contact with the right kind of books and a teacher who has made it his or her first aim to develop their potentialities as readers? It is probably true that in reading we discover more plainly than in any other sphere of school activity the uniqueness of the individual person. Boys and girls can be packed in masses of thirty, forty or fifty and rendered reasonably competent to perform certain kinds of skill, but it is impossible by mass instruction to implant a genuine taste for literature. Teachers can, however, do two things: they can by skilful classwork in their English lessons offer their pupils certain examples and explain the reasons why they are generally appreciated, and they can, as the counterpart to that instruction, offer them in the school library a range of choice and a word of advice suited to their individual needs. By no means all children will reach the level of taste aimed at, however rich the variety of books offered, however gradual the ascent, however tactful the librarian; perhaps disappointingly few will do so. What then? What right have we to say they should? The question we have a right to ask is: has this boy or girl reached the level of which he or she is capable?

[page 26]

CHAPTER V

THE CONDITIONS

WHAT HAS BEEN SAID may often have appeared to take for granted a large and well-found library in a school of some size. But for some of the activities referred to the only ultimate essentials are a collection of suitable books, supplemented, perhaps, by the resources of the public library, and a clear idea in the mind of the teacher about the use to make of them. Given these, the principles involved in bringing pupils and books together are applicable in almost every school, whatever its size and circumstances. Certain facts cannot be ignored, however. The results that can be hoped for will be governed to some extent by three conditions, namely (i) the material circumstances of book supply, accommodation and furniture, (ii) the skill of the school librarian in the selection and management of the books, and (iii) the amount of opportunity created by the school organisation for the use of them.

(i) The supply of books is improving. Local education authorities are now more generous in their grants for the purchase of library books, and public librarians are showing the utmost goodwill in coming to the assistance of schools in every way possible.

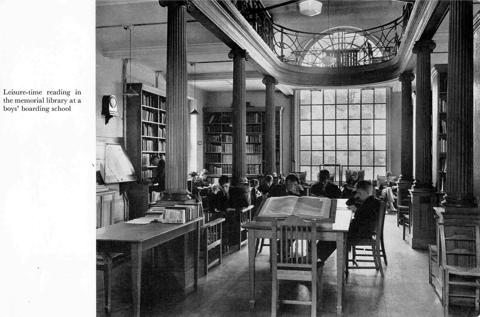

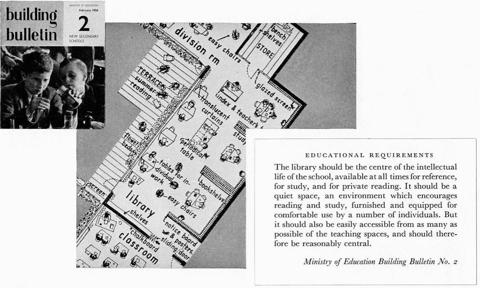

Scarcely less important are accommodation and furniture. 'The arrangement and furnishing of the library', said the Carnegie Report, 'should create an atmosphere such as will give the reader, on entering, the immediate impression of space and light, ample and welcoming, with a reassuring promise of quiet and detachment from the unavoidable noise, hurry and interruptions of the ordinary classroom life.' Architects and furniture designers have striven to realise this ideal, and now a certain number of school libraries, although few in relation to the total, are in satisfactory surroundings. The Building Regulations, 1944, foretold the expansion of library accommodation to come, and Building Bulletin No. 2 suggests how sound principles of planning can be embodied at reasonable cost. But many schools are having to make the best of moderate or poor resources and some of them are doing so with marked success. There are

[page 27]

numerous examples of improvised libraries working with a high degree of efficiency in premises designed for quite other purposes, frequently in a classroom, but in some instances in a hall or corner of a hall, a medical room, a cloakroom or a corridor. No less ingenuity has been shown both by local education authorities and by individual schools in converting disused or outmoded furniture into tolerable shelving, tables and chairs.

(ii) It is in the selection of their books that the less experienced school librarians meet their greatest challenge. Too frequently the books on the shelves of a school library show a want of balance that does injustice to some section of the school or to some of the pupils' main interests. Sometimes they have too much the appearance of a random collection assembled without any clear view of the purpose to be served. Some libraries are cumbered with volumes that are never read and would be better elsewhere. A good library faithfully reflects the current life of the school.

The management of the books calls for a certain amount of special knowledge and skill. The importance of using good and recognised methods has already been mentioned (p. 15). Courses of short duration are organised for teachers by the Ministry of Education and by local education authorities to give an introduction to the principles and practice of school librarianship; longer courses are available for those able and willing to undertake deeper study and gain wider experience. Much may, however, be learnt from books, from the various publications of the School Library Association and from personal contact with the librarians of public libraries, to whose generous and able co-operation a large number of teachers are deeply indebted. The task is not so difficult that any teacher need feel debarred from making a start on it.

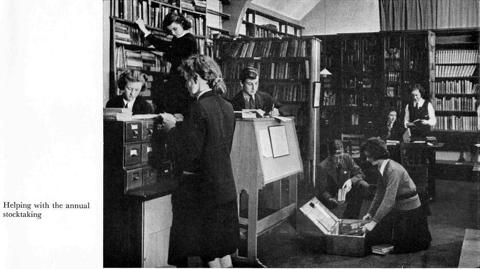

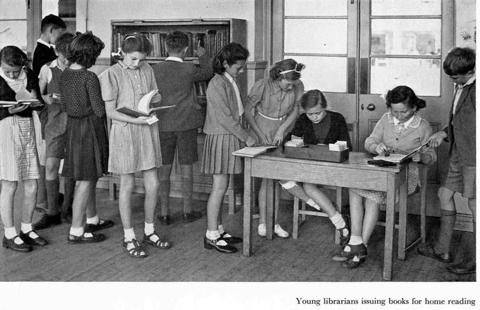

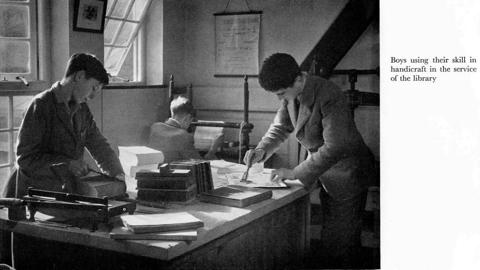

A large share in the management of a school library may properly be taken by the pupils. Its claim on voluntary service is a reasonable one in that it offers in return a valuable opportunity of learning to take administrative responsibility and to carry it with business-like efficiency. A board of pupil librarians can be organised to provide assistants for much of the work entailed. If these are suitably distributed in age range to secure a succession of senior librarians who have gained experience under their predecessors, many of the routine tasks will be quietly and effectively carried on with little intervention by the master or mistress ultimately responsible. That this teacher should have sufficient knowledge of school library management, should have organised the routine on sound principles, and have given thought to the training of the pupils, needs no emphasis.

[page 28]

(iii) Organisation. Schools have been known to possess a library and to keep it locked except at stated times when the librarian was in attendance for the issue and return of books. Others have been known, and indeed are still not rare, that have a number of books but no teacher with special responsibility for them and no regular system of putting them to use. In others, again, the timetable is so arranged that only a minority of the pupils has any opportunity to use the library except for borrowing. In yet others the pressure on accommodation has been too readily allowed to rule out the use of a room as a library. These are illustrations of the way in which the influence of the library is limited by the pattern of school organisation. The relationship between pupils and books finally depends on such factors as the assignment of responsibility to a member of the staff competent and willing to undertake it, the use of accommodation with due regard for the claims of the library, the arrangement of the daily routine to allow full use of the books, and - what has been assumed without apology - the easy discipline of a well-ordered and happy community.

A final word to school librarians. To their predecessors this pamphlet owes its substance and its inception. If in these pages a great deal has been asked of them - that they should make themselves masters of the art of selecting books and of the technique of school library administration, that they should be guides and tutors to the boys and girls exploring their bookshelves, that they should consult and serve their colleagues as well as appealing for their co-operation - it is because teachers of vision and devotion have themselves set the example and created the standards for this new branch of their craft.

[page 29]

APPENDIX

SOME PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS

THIS summary of practical suggestions is addressed chiefly to teachers who are undertaking school library responsibilities for the first time, whether it be the creation of a new library or the taking over of one already established.

GENERAL

Many books and articles have been written about librarianship and a number about school librarianship, and some of them should be read. A very full list (1), with descriptive notes, has been published (second edition, 1950) by the School Library Association, Gordon House, 29 Gordon Square, London, W.C.1. The other publications (various pamphlets and the terminal periodical, The School Librarian) of this Association, and those of other bodies such as the National Book League (7 Albemarle Street, London, W.1), the Incorporated Association of Assistant Masters in Secondary Schools and the Library Association, are valuable. Primary Education (H.M. Stationery Office, 1959, price 10s. 0d.) and several of the pamphlets of the Ministry of Education, referred to previously in footnotes, contain relevant material.

The inexperienced school librarian can learn a great deal from personal contacts. He should seek advice and help from public librarians and from his fellow school librarians at local and national meetings.

THE SELECTION OF THE BOOKS

Most of the societies referred to above, and many public libraries, issue useful book lists which should be consulted. Newspapers and periodicals carry helpful reviews of children's books, and book exhibitions provide an excellent opportunity for the librarian himself to 'browse'. Many county libraries offer special facilities to school librarians, of which full advantage should be taken.

The school librarian should be familiar with books about children's reading. Reference to the chief works, and to a number of periodicals and book lists, will be

(1) List of Books on Librarianship and Library Technique of Interest to School Librarians. The same pamphlet, price 2s. 6d., also contains A List of General Reference Books suitable for Secondary School Librarians.

[page 30]

found in the School Library Association's list of books on librarianship already mentioned.

THE ARRANGEMENT OF THE BOOKS

As soon as a small number of books has been acquired, the need for their orderly arrangement on the shelves will become apparent. In some school libraries the books are arranged roughly according to school 'subjects'. Very soon, however, it is found that some of the most popular and informative books do not fit easily into these categories, while others relate to several 'subjects'. A scheme is clearly required which will provide a place (and as far as possible only one place) for every book, with a system of letters or numbers which will make it easy to find any book. If this scheme is well worked out and covers all knowledge, it will guide pupils both in their browsing and in their selection of books for study and it will give them a glimpse of the relationship between the different fields of knowledge.

The invention of such a system is an expert task, and there are many arguments in favour of adopting one of the recognised systems of library classification. The arguments for each of these, and suggested modifications for school libraries, will be found in the literature of school librarianship. The advice of an experienced school librarian will be very valuable on this point.

RECORDS AND CATALOGUES

It is necessary to keep a careful record of the books put into the library. Since this will be permanent, it is best made in a well-bound book, called the accessions register; in it each volume is given an individual number and all its particulars are entered. Stout books, ready ruled, are sold for the purpose.

To enable pupils to use the library intelligently, and to help in the checking of the books, some form of catalogue is required. These are usually made on standard cards, one for each entry, though other forms of catalogue are used for some purposes. School library catalogues may well be simpler than those of large public libraries, but they should be accurate and informative.

Records of books issued enable the school librarian to follow the reading of individual pupils and note the relative popularity of the books.

ISSUING THE BOOKS

The school library ought to have a business-like system for issuing books which will not take up too much time and labour. The various systems - that of the public library, book-card, reader's card, book-slip - fulfil slightly different purposes and should be considered carefully

[page 31]

before a decision is made to adopt one of them. Whichever method is used, arrangements are needed for filing the cards or slips in some simple order so that they may be quickly found when the books are returned.

FURNITURE AND EQUIPMENT

Physical conditions contribute very considerably to the school library atmosphere. It is part of the librarian's responsibility to see that the library has the best shelving, tables, chairs and equipment that circumstances will permit. The chief items of equipment to be borne in mind are the librarian's desk or table, the cabinet of drawers to hold catalogue cards, the trays for the filing of issue cards or tickets, neatly mounted or framed labels for shelves and bookcases, and display boards for notices and bookjackets. These items may be studied in a good public library and in the illustrated catalogues of the library furnishers.

HELP FROM COLLEAGUES AND PUPILS

The resources of the school library are immeasurably strengthened when all the books are in one collection under one administrative control. In a large school library there may, of course, be more than one librarian. But the understanding co-operation of colleagues is essential if the library is to realise its full possibilities, and everything possible should be done to cultivate it. This co-operation is often given formal expression by means of a Library Committee and a well-used suggestions book.

The routine work of administering a school library would fall heavily on a librarian working alone. But, as has already been suggested, pupils can always be found who are able and very willing to help, and if the work is well organised it is of great value to them. Many who are otherwise undistinguished find in the school library a niche which they can fill with credit.

LIBRARY PERIODS

These words frequently appear in the literature of school librarianship and in discussions on it, and it is interesting to note that they do not always bear the same meaning. While it is probably not possible, or even desirable, to reach an agreed definition of' library periods', it is well to know what the term means in any particular context. The different kinds of activity to which it refers all have their value and are, of course, not mutually exclusive.

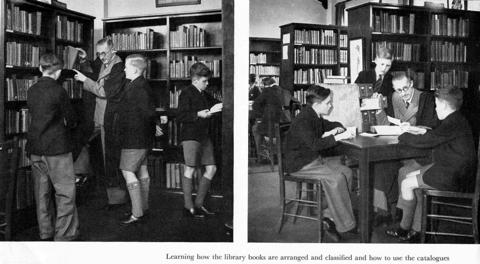

(a) It may mean a period in which a class goes to the library for instruction in its use. This may take the form of an introduction to the library for newcomers, during

[page 32]

which the school librarian briefly describes the classification system and the arrangement of the books on the shelves, and possibly the use of the catalogues; or it may be expanded into a series of lessons on 'How to find a book', and go on to such topics as the use of reference material (a wide subject) and the planning of elementary research.

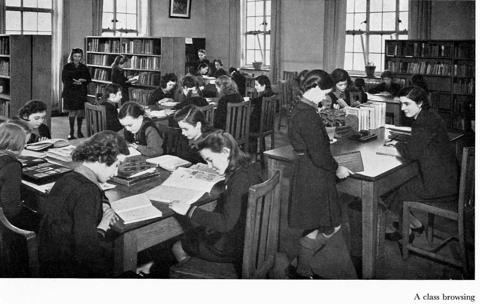

(b) It may mean a period in which a class goes to the library to explore its resources, to browse, and perhaps to change books. Here the function of the librarian is to stimulate and advise readers individually. Much of the value of such a library period would be lost if it were to be used solely for the business of book-borrowing.

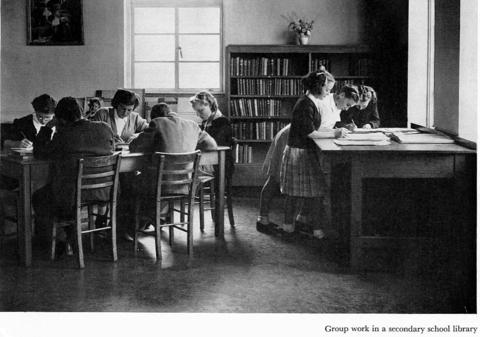

(c) It may mean a period, spent either in the library or in the classroom, during which pupils are reading books for pleasure or using them for individual or group research. A form or subject teacher may be in charge of this activity, but the librarian will probably have had a hand in the choosing of the books in advance. This kind of co-operation between the librarian and the subject teacher is an example of the way in which the library can permeate the life of the school.

'Books are the masters who instruct us without rods or ferules, without hard words and anger, without clothes or money. If you approach them they are not asleep; if, investigating, you interrogate them they conceal nothing; if you mistake them they never grumble; if you are ignorant they cannot laugh at you. This feeling that books are real friends is constantly present to all who love reading.'

Richard de Bury, Bishop of Durham. 1344.