[page 116]

APPENDIX V.

MEMORANDUM ON EMPLOYMENT OP MOTHERS IN FACTORIES AND WORKSHOPS

By Miss A. M. Anderson, H.M. Principal Lady Inspector of Factories

1. The main points for consideration are:

I. The existing law, its means of administration, and its effects.

II. The extent and its effects in particular localities and trades, or generally, of employment of mothers of infants in: (a) Factories and Workshops under regulation; (b) unregulated occupations of a kind comparable or likely to be equally injurious.

III. The circumstances and causes of employment of child-bearing women in occupations separate from their homes and the forces to be reckoned with if the existing law were to be strengthened or extended.

IV. The existing means and agencies, other than direct prohibition of employment, for enabling and fitting mothers to devote themselves both before and after confinement to the necessary care of the infant life.

V. Opinions quoted re amendment of the law.

I. THE EXISTING LAW AND ITS ADMINISTRATION

2. So far as the Factory Acts (which have hitherto aimed primarily at safeguarding the life and health of the worker herself or himself under a contract of employment with an occupier of a factory and workshop) are concerned, the existing law (1 Edw. vii., C. 22.. S. 61) is. as it has been since the repealed Act of 1891 (Section 17) came into force, as follows: That an occupier of a factory or workshop (or laundry since 1895) shall not knowingly allow a woman to be employed in his factory or workshop within four weeks after she has given birth to a child.

3. Thus no legal offence has arisen unless the occupier or his agent has, with knowledge of the fact and date of the birth, employed or re-employed the mother of the child. No responsibility has been laid on the father or mother in this matter by the Factory Act, and no means are prescribed to aid the employer of the mother in finding out the fact of the birth and its date, or ascertaining the physical fitness of the mother to resume work. The question of the physical fitness of the infant to be left by the mother has, of course, not entered into consideration. There are naturally many cases where knowledge of the fact and date of birth would be out of reach of cognisance by the occupier; for instance, where the mother herself changes her place of employment, and being under no legal obligation to state to the employer the date, or even the fact of the child's birth, commences a new contract of employment.

4. No case was taken under Section 17 of 1891 until six years after it had become law. In 1897 proceedings for a contravention were first instituted by one of the lady Inspectors in a Yorkshire town. On this case I reported to the Chief Inspector, Annual Report, 1897, page 96, as follows:

Hardly any infringement of the Factory Acts is more difficult to discover or proceed against than the employment of a woman within four weeks of her confinement, chiefly owing to the burden of proof resting with the inspector as to the employer's knowledge of the facts. Although we have good reason to believe that such employment occurs frequently in certain districts, only one clear case, namely, this one, has yet occurred within our knowledge as suitable for proceedings, and in this case it was owing to the fact that the woman was sent for by the foreman who was pressed for workers, on the ninth day after her confinement, although he had been informed of the reason for her absence on the day she left the mill. This unfortunate woman, although she made some attempt to screen her employers when called as witness by Miss Squire, was nevertheless dismissed from her employment after the result of the case (conviction and small penalty) was known. She obtained employment from one of the magistrates who heard her case soon afterwards, and this removed her personal difficulties*; it would do little or nothing however, to counteract the effect on the workers' minds of the conduct of the employer, who, by dismissing her, showed his contempt for the law and the kind of course he was likely to pursue with any worker who admitted facts as to infringements of the law to one of H. M. Inspectors.

Miss Squire herself reported at the same time as follows:

Section 17, 1891, although of so great importance to the community, no less than to the individual, must remain for the most part a dead letter, owing to the difficulty of proving the employer's knowledge of all the circumstances, as well as for other obvious reasons. It is probable that much greater control over the evil with which this section is intended to cope could be exercised, and also that both the appearance and the reality of hardship entailed by the present regulation upon mothers dependent upon their earnings would vanish if the production of a medical certificate of fitness for employment in the particular factory to which it referred were made the condition of employment or re-employment after confinement.

In the case in question the mother of the infant had absolutely no choice but to take such work as offered, when and where she could obtain it, as she was unmarried and had no means of support.

5. Other cases have since them come before me for consideration, but until the present time in only two (both married mothers), after a considerable interval of time (in 1902 and 1903), has it been possible to institute proceedings for breach of the law. In four out of seven cases of employment in a factory within four weeks of childbirth, which have been reported to me during the present month, the legal cases fell to the ground because either the mother sought work in a fresh mill without mention of her infant, or having left her work some time before her confinement she returned after such an interval of time that the occupier was under the belief that the section had been duly observed. In the majority of these cases outside the section the mother is unmarried, or deserted and destitute. Three cases are about to be heard, two in Scotland and one in England, and the decision of the courts will be shortly accessible to the Committee.†

6. During the seven years that I have been directing the work of the lady inspectors, complaints have been received repeatedly of cases believed to be contraventions of the section as well as of general injury to the health of the mothers and infants through early, though not illegal, return to work. All have been thoroughly investigated, with the result, so far as prosecution is con-

*The industrial Law Indemnity Fund, organised by Mrs. H. J. Tennant, now affords support and assistance to find fresh employment in any case where a woman or girl is dismissed for giving true evidence on a contravention of the Factory or Truck Acts.

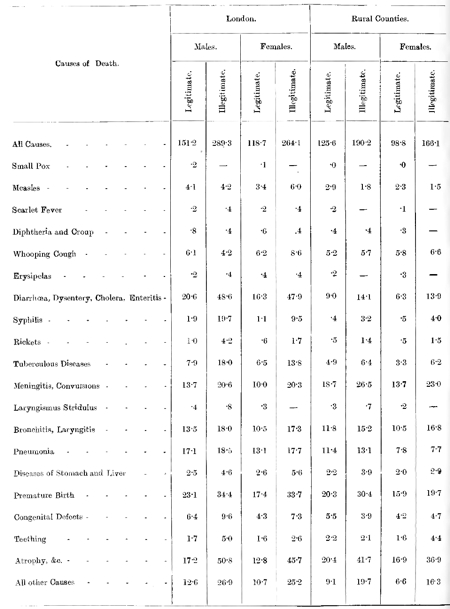

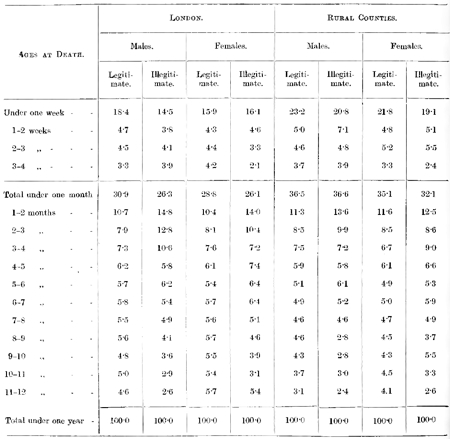

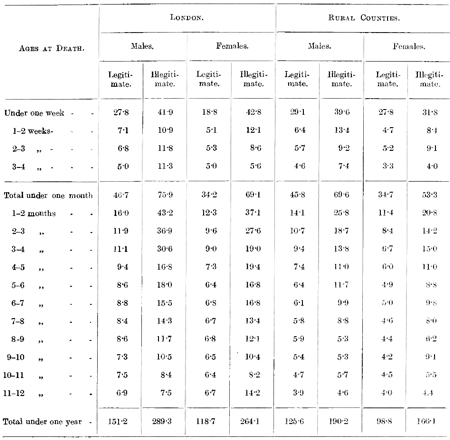

†I have just received the report on the decision of the magistrates in one case heard in Preston yesterday. There it was proved that the mother returned to work in the same mill within four weeks (reason, poverty, husband out of work), that the agent of the occupier, the foreman knew the reason for the woman's absence and that he sanctioned her return, omitting to ask her the age of the infant. The magistrates decided that the occupier did not "knowingly allow" the woman to be re-employed, although they blamed the foreman for not making the inquiry which would have elicited the fact of the infant's age.

[page 117]

cerned, already stated. On the other wider question, the evidence of doctors, nurses etc., has always been conflicting.

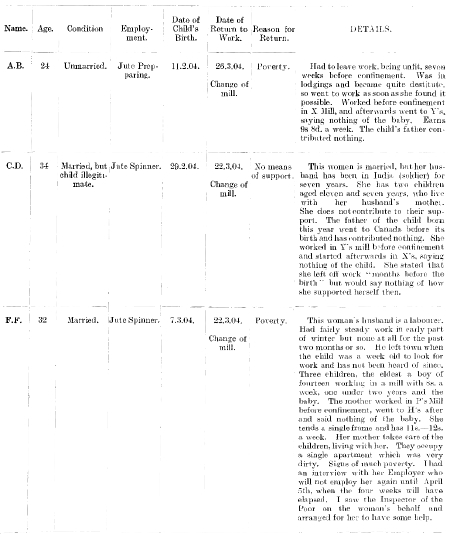

7. There can be no question that, while the prohibition is well known in factory districts, and absence for one month fully observed in the majority of cases, especially where pressure of circumstances does not lead the mother to seek early re-employment and wages, there are yet many cases where the spirit if not the letter of the present law is broken. The following are cases found in one town in a single week's brief enquiry:

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

8. It is hardly to be doubted that there would be a multiplication of such evasions of the prohibition if it were mechanically extended to three or more months without other amendments of the section tending to make administration more effective than it can be at present. Further, although the present limit of one month is (naturally) most willingly observed by all mothers with means of support, an extension to three months or longer would presuppose the introduction of a real change of practice amongst married mothers in a considerable number of cases (as will be seen by evidence presently to be offered). The consideration would then have to be faced, assuming the section to be made effective by throwing the onus of inquiry on the employer and declaration of the birth on the parents, whether the existing staff of inspectors would be adequate to enforce respect for the extension of the law. One of the inspectors reporting for the purpose of this memorandum, indicates to me her belief that an extension of the time limit must influence to some extent the marriage and birth rate, and another, while approving further restriction, says, "I realise thoroughly the dangers attached to the restrictions, and that increased vigilance would be necessary on the part of other authorities."

9. In view of the difficulties of administration in England of the four weeks' limit, reference should be made to the law in other industrial states of Europe although it would be impossible without careful enquiry on the spot to ascertain how far either by local custom or by methods of administration, the law in those countries is realised in practice.

10. The limitations as regards employment of women after child-birth may be briefly summarised as follows::

[page 118]

Belgium: 'Women must not be employed in industry within four weeks after child-birth' (section 5 of the Law of 5th December 1889.)

Switzerland: 'A total absence from employment in factories of women during eight weeks before and after child-birth must be observed, and on their return to work proof must be tendered of an absence since the birth of the child of at least six weeks' (section 15 of the Federation Law of 23rd March, 18 77). An order of the Federal Council, 1897, indicates a further abstinence from employment before confinement (the length of time unspecified) in certain dangerous occupations, e.g., in processes in which fumes of white phosphorus are produced; or in manipulation of lead or lead products; or where mercury or sulphuric acid are used; in dry cleaning works; in india rubber works; any processes involving lifting or carrying heavy weights, or risk of violent shocks. As the limit of the period is undefined, and means of enforcing the prohibition unspecified, it is difficult to see how the regulations does more than outline an excellent theoretical protection.

Holland: 'Women must not be employed in factories or workshops within four weeks after childbirth.' (Law of 5th May, 1899.)

Denmark: 'Women must not be employed within four weeks of child-birth except on production of a medical certificate showing that the mother's employment mil not be injurious to herself or the child.'" (Law of 1st July, 1901.)

Germany: The industrial code contains the same prohibition absolute of employment during four weeks as the Dutch Law, but extends it to six weeks if a medical certificate cannot be produced approving employment at the end of four weeks.

Austria: The Industrial Code lays down the same prohibition as the Dutch Law.

Spain: By a law of the 13th March, 1900, prohibits employment of women within three weeks of childbirth, but lays a further obligation on employers to allow one hour at least in the ordinary period of employment (for which there must be no deduction from wages) to nursing mothers to nurse their infants. This hour may be divided into two separate absences of half-an-hour, and may be fixed at pleasure by the mother, whose only obligation is to notify the time she chooses to the overlooker."

Quoted from "Dangerous Trades" (Comparative Survey of Legislation), edited by Thos. Oliver, M.D., etc. Published by John Murray, 1902. pp. 53-54.

II EXTENT AND EFFECTS OF THE EMPLOYMENT

11. The extent of employment of mothers in (a) regulated and (b) unregulated work of a comparable kind can only roughly be arrived at by considering the census returns with special reference to the particular centres of women's main industries, and above all those centres where at the same time men's industries for the same class are lacking or scarce. The occupiers' returns for factories and workshops give no information as to the proportion of married women; and the inquiries of inspectors on this point in individual factories have to be made with great care and discretion in the absence of direct legal right (where section 61 is not in question) to make such inquiry. The Registrar's records of births and of deaths, which might be invaluable in throwing light on this important question of the occupations of mothers of young children and infants, show only in the case of illegitimate infants the occupation of the mother. The value of the information in this case makes it appear the more regrettable that a record which could have been so easily obtained has not been kept of the occupation of married mothers, and of mothers of still-born infants at the cemeteries and work-houses. (It may be noted in passing that attention was drawn at the International Congress on Hygiene in Brussels, 1903, to the lack of any general records of still-births in great Britain, and the consequent difficulty of comparing the figures as to infant mortality with those for other countries of Europe.) In certain towns, of which Preston, Bury, and Leeds may be named (although there are others), information on the occupations of the mothers of infants dying under one year of age is, or shortly will be, available in a certain number of cases, as the result of inquiries instituted through lady Sanitary Inspectors or Health Visitors by the Medical Officer of Health. In Black- burn a valuable voluntary record has been kept by the Registrars for the use of the Medical Officer of Health, of the occupations of the mothers in the case of all births and Miss Squire has drawn from this record an interesting table to which I refer presently.

12. As regards the effect of employment of mothers in factories, workshops, laundries, or as charwomen or in similar hard work away from home or in heavy domestic work at home, no general information, so far as the health of the mothers themselves is concerned, of a statistical kind is available*; particularly is such information incomplete in some of the centres selected for this memorandum (on account of the unusual proportion of married women in factories), for there it is reported to me (especially by Miss Squire for Blackburn, Preston and Burnley) that there is no lying-in hospital, that maternity cases are not taken in at the infirmary, and an insignificant amount of charitable assistance otherwise afforded.

13. "The workhouse is the only institution where patients are admitted for their confinement and here they are of course destitute cases." Enquiry has to be made at length of physicians and surgeons, nurses and midwives in such districts. As regards the effect on the infants, much may be learnt from the comparison of local and general infantile mortality rates, with particular reference to (a) presence (b) absence of much employment of mothers, if careful local enquiry be at the same time made as to presence or absence of other recognised causes of high infantile mortality (insanitary surroundings, ignorance of maternal duties, intemperance, poverty, use of means of prevention of child-bearing). The mere fact of extensive employment of mothers in factories in a locality cannot be regarded as significant by itself without reference to the factors of length of hours, character, and condition of the work itself (which vary enormously from one industry to another) and to the ordinary standard and practice of the mothers in the district as to care of infant life.

14. The enquiry of three inspectors on my staff has been during a few weeks directed towards increasing in three main centres, viz., Dundee (jute trade), Preston, Burnley and Blackburn (cotton trade), Hanley and Longton (pottery trade), our available knowledge of the above indicated extent and effects of employment of mothers, adding consideration of the moral and economic effects as well as of causes of such employment. Two characteristic conditions all these towns have in common: (1) presence of a large concentrated industry necessarily employing many women and with a large proportion of married women amongst them; (2) absence of other important occupations for women. Two of these towns, Dundee and Preston, have a characteristic absence of or insufficiency of industrial employment for men of the same class as those of the women employed. The three Lancashire towns stand apart from the other towns named in respect of the comparatively high standard of living established and deemed essential by the workers in question. Serious struggling poverty in the ordinary sense which is prominent in parts of Dundee and in parts of the pottery towns is generally absent in the Lancashire towns. In all these towns the infantile mortality is high, although as regards some of the towns equally and almost equally high rates are elsewhere to be found where the industrial employment of mothers is not a special feature or where the mothers mostly remain at home. In all of the towns a very striking degree and amount of ignorance of maternal duties, especially of feeding and cleanliness, is at once evident, but the general sanitary conditions in the matter of housing and surrounding sanitation vary widely. Other widely varying conditions are seen in the nature of the work of the factories, in the length of hours, pressure and speed of work, heat, dust, and other sanitary conditions.

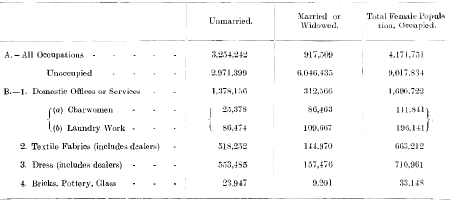

EXTENT AND EFFECTS

15. Turning now to the extent of employment of married women and mothers, it is convenient to bear in mind the general extent of such employment as shown in the census

*Except such as might be indicated through careful comparison of the ratio of mortality from special women's diseases to the female population in selected districts. No idea would be given of the amount of illness, nor could it be precisely stated from existing records which occupations were concerned.

[page 119]

1901. This information is given only for England and Wales, not in the census reports for Scotland and Ireland. In England and Wales more than two thirds of the married or widowed women employed in occupations are to be found in the following groups: (a) Domestic offices, including all laundry workers and charwomen; (b) textiles; (c) dress. The highest ratio of married women is among the laundry workers, whose trade is very little regulated; taking those two branches together, while the total number of women over ten years employed is less than half that in the textiles groups, yet actually a larger number (absolute, not relative) of married women are employed than in the textile group. The details are shown in the following table:

OCCUPATIONS OF WOMEN. FEMALE POPULATION OVER TEN YEARS IN ENGLAND AND WALES. CENSUS 1901

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

The ratios, however, are not the same when we come to consider selected districts.

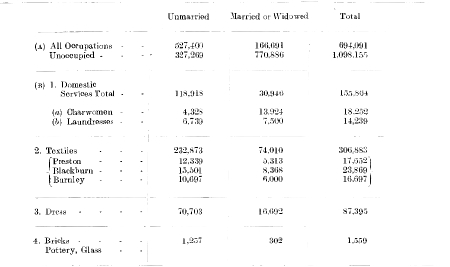

LANCASHIRE

[click on the image for a larger version]

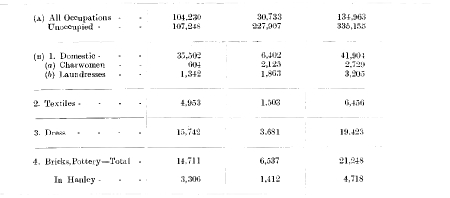

STAFFORDSHIRE

[click on the image for a larger version]

STAFFORDSHIRE

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 120]

16. Looking further into the census figures for Blackburn, Burnley, Preston, it appears that more than half the women over fifteen years of age in the cotton mills of Blackburn and Preston are married or widowed, whereas \tiBs than one third are so returned for Burnley. In Blackburn, 31,445 women were returned as occupied (out of 68,660 females), of these 20,906 were in cotton mills; in Preston 25,279 women were returned as occupied (out of 51,669), and of these 16,317 were in cotton mills. Miss Squire estimates that of the total number of occupied women in Blackburn, 37.9 per cent, are married or widowed as compared with 30.5 in Preston and 33.5 in Burnley. I have not been able yet to work out all the corresponding percentages for the Pottery towns, but Miss Martindale gives the following estimate of the percentage of married and widows in china and earthenware factories to the female population between eighteen and fifty years of age: Longton, 20.6; Hanley, 9.7; Fenton, 14.0; Burslem, 13.6; Tunstall, 9.6; Stoke, 7.1.

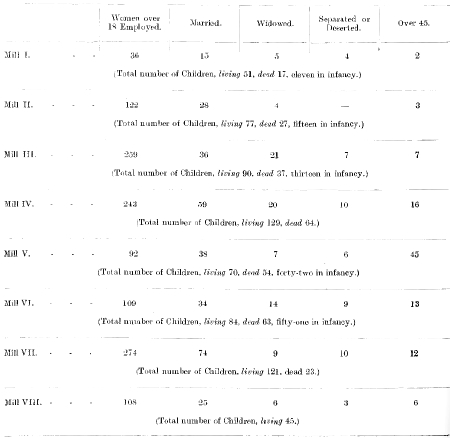

17. In Dundee, which in population takes the third place among Scottish towns, and where a larger proportion of occupied females is found than any of the others, the chief employment for women is the manufacture of jute. As the census gives no information about married women the only way of arriving at any estimate is to glance at the figures as to all women occupied, 57.7 per cent.* out of 72,723, at the total number employed in jute mills, 24,879, of whom 13,719 are between twenty and forty-five years of age, and then to proceed, as Miss Paterson did, to take particulars in a group of mills. She says:

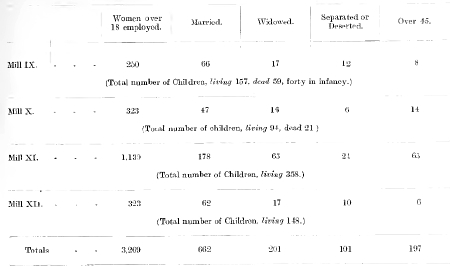

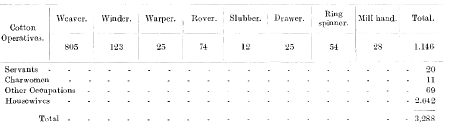

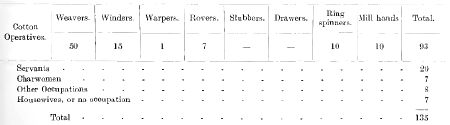

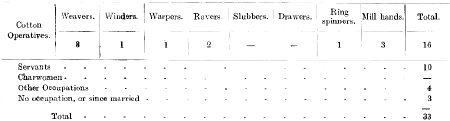

I visited a group of mills in the north east quarter of the town. These may be taken as representative. ... I found it best to make my inquiries personally in the mills, the foremen do not know which women are married and which are not, and they cannot be relied on to get the information correctly from the workers who in one mill where the attempt had been made found great pleasure in giving absolutely misleading information. I, therefore, visited for the purpose twelve jute mills, in which a total of 3,269 women over eighteen years of age are employed. In this way I got information at first hand with regard to the married women, but not the unmarried mothers. In almost all cases I got the information I asked for as to numbers and ages of children and the provision made for them during absence at work, but there was, of course, much greater readiness on the part of some women to give details than was shown by others. On the whole, however, the difficulty was not to get information. . . but to avoid giving hastily the advice so eagerly sought for. . . I found that the managers generally were of impression that they employed more married women than I found they did, but they no doubt included the unmarried mothers.

18. In order to estimate the extent of employment of un- married mothers, Miss Paterson searched the Registrars' books for details of occupations of mothers of illegitimate infants in 1903. Out of 4,024 births, 400 were illegitimate, and in 278 of these cases the mothers' occupation was given as textile operative. Many of these cases Miss Paterson visited in their homes as well as many of the married mothers. She found that in the majority of the cases no contribution towards support was made by the father of the illegitimate child.

19. Miss Paterson's details about the 12 Jute Mills may be summarised as follows:

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

*Paisley follows second with 43.4 per cent.; Edinburgh third with 43.3 per cent.; Glasgow fourth with 38.9 per cent.; Aberdeen fifth with 35.4 per cent.

[page 121]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

20. As the census figures distinguish the ages from fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, etc., and all the factory regulations and returns distinguish those above and below eighteen years of age, comparison of the two sets of figures for percentages is not satisfactory. A rough estimate, however, may be made for purposes of comparison with the figures given above for cotton mills in Preston and Blackburn that one-fourth of the women employed in Dundee jute mills are married or widowed.

21. It is impossible, as already pointed out, to make any statistical comparison as regards numbers of mothers of young infants employed in the mills (although, as I shall presently indicate, the inspectors have gathered much scattered information bearing on this point). For Blackburn alone have we got the general figures as to births presented in the following Tables by Miss Squire for the year 1903:

BLACKBURN

Births registered in 1903 with Mothers occupation.

Total Births

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

22. Most unfortunately, this interesting information cannot be brought directly to bear on the problems before us, through lack of parallel information as to the occupations of the mothers in the case of infant deaths. The influence of occupation can only be guessed at by the particulars afforded in the next two tables as regards illegitimate births, and deaths of illegitimate infants under one year in Blackburn during 1903; the figures are so small that too much weight must not be attached to the relative infant mortality. When it is remembered, however, how much higher the infantile death rate is amongst illegitimate children generally than amongst legitimate, and that the general rate in Blackburn ranges from 157 in 1902 to 221 in 1900, it is seen that the death rate shown in the second table affords no positive ground for attributing a specially high rate to the cotton mills alone. A similar observation has been made by the Medical Officer of Health for Bury in his report for 1902, after a systematic inquiry made into the occupation of the mother of every infant dying within the year within his borough; in that inquiry the basis is broader than in the following Tables.

BLACKBURN

Illegitimate Births

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 122]

BLACKBURN

Deaths of Illegitimate Infants under one year

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

These figures are for two registration districts only, i.e., north and south. Witton registration district is omitted owing to not being able to go to the registrar's office. This table is, therefore, incomplete. But there was only one illegitimate birth registered in the Witton district, a servant's child.

23. The parallel figures for Preston and Burnley follow in the next two groups of Tables:

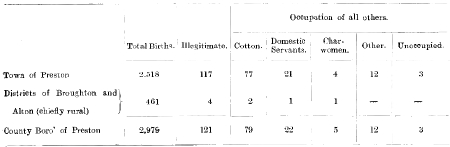

PRESTON

Illegitimate Births

For first-three quarters of year 1903, viz., Jan. 1st to Sept. 30th

[click on the image for a larger version]

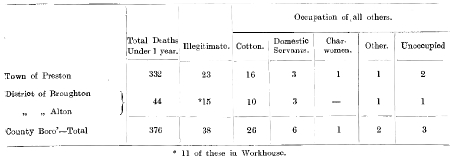

Deaths of Illegitimate Infants under 1 year

Jan. 1st to Sept. 30th, 1903

[click on the image for a larger version]

Deaths of Illegitimate Infants under 1 year

Jan. 1st to Sept. 30th, 1903

[click on the image for a larger version]

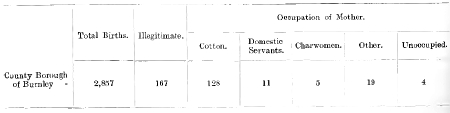

BURNLEY

Illegitimate Births - Year ending December 31st, 1903

[click on the image for a larger version]

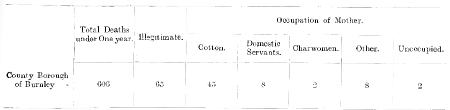

BURNLEY

Illegitimate Births - Year ending December 31st, 1903

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 123]

Deaths of Illegitimate Infants under One year - Year ending December 31st, 1903

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

24. The results as regards the one point of infantile mortality in relation to occupation are in this present inquiry similar to those I have had reported to me on isolated inquiries in the past. For example, in 1898 complaint was made to me that among the infants of hearth rug weavers in and near Huddersfield (a very rough type of workers), an excessively high mortality occurred; it was alleged to be at least 50 per cent. All the factories were visited by Miss Squire, and close investigation made as to the ratio of mothers among the weavers, condition of the infants, time before and after confinement for leaving work; registers were searched, doctors and midwives, employers and others interested consulted. A considerable proportion of the mothers were unmarried, but no definite relation between the occupation and the infant mortality could be established. The alleged mortality of 50 per cent was certainly not supported by the facts discovered. Although the industry and the figures are small the investigation was of interest, as knowledge can only be gained by successive consideration of all the facts in definite selected areas and industries. Although it is certain that the rate of infantile mortality is only a very rough guide (if any) to the effect (which is moral as well as physical) of the mother's occupation on the health of her surviving children, it is of the utmost importance that we should be able to follow the clue further than with existing records we are able to do.

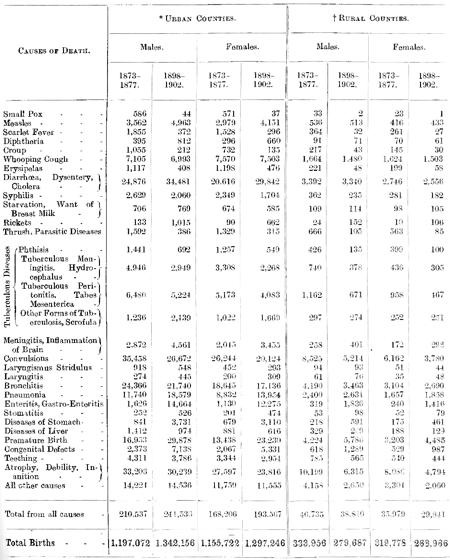

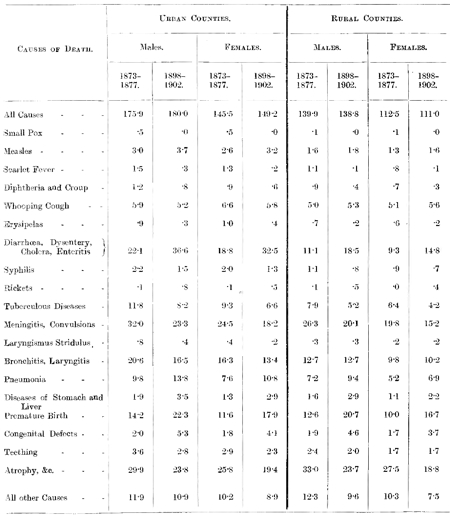

25. Two directions in which information is lacking which we need are: (a) localisation of the infant mortality rates in a systematic way for particular areas in industrial towns where the workers of selected industries live; (b) general infant mortality rates for selected industries throughout the country.

26. (a) As regards the first of these points, a comparison of the rates in the special centres I refer to with those for non-industrial towns and counties would show what I mean. Dundee with 57.7 per cent occupied women (and about one-fourth of the women in the jute mills married) has an infantile mortality rate varying from 217 in 1893 to 142 in 1903 (average during representative years 1890 to 1899 is 179). Glasgow with 38.9 per cent occupied women had rates varying from 149 in 1901 to 134 in 1903. but in the Brownfield district the rates run far higher (242 in 1901, 233 in 1903, much beyond any localised rate in Dundee).

The whole of Scotland with 37.26 per cent, occupied women has a rate of 129.3.

Hanley with 35.8 per cent occupied women, and 19.8 per cent in the potteries (of whom 5.9 per cent are married) has an average mortality rate of 204 (209 in 1900, 212 in 1901, 170 in 1902).

Longton with a rather larger percentage of women and of married women occupied* has an average infantile mortality rate (ten years) 239 (255 in 1900, 225 in 1901, 195 in 1902).

Throughout Staffordshire the average rate over ten years is 172 and 1901 fell to 164.

We may compare some other counties where there is far less industrial employment for women:

Durham average: 167, risen in 1901 to 179.

Northumberland: 160, risen in 1901 to 182.

South Wales: 163, risen in 1901 to 170.

Returning to the county of Lancashire, we find that the infantile mortality rate has remained practically stationary for eleven years, and was 179 in 1901 (average for ten years previously: 179).

Preston with nearly half its female population "occupied", of whom about-two thirds are in cotton mills, has an average infantile mortality rate (ten years to 1900) of 236; 30.5 of the total occupied females are married, and of women over 15 years of age in cotton mills one half are married.

Burnley with a larger proportion of its female population in cotton mills, has an average infant death rate of 210, fallen in 1902, an exceptional year, to 177; 33.5 of the total occupied females are married, and of women over 15 in cotton mills rather more are married than is the case in Preston. This is in a town where Miss Squire found far more ignorant neglect of infants than in Preston.

Blackburn with nearly a half of its female population "occupied", under a third of whom are in cotton mills, has an average infant death rate of 200: 37.9 of the total occupied females are married, and of women over 15 years in cotton mills over two-thirds are married.

From this rough outline it is clear that much more localised information with reference to sanitary surroundings in selected areas is necessary before we can definitely connect the infant death rate with the occupation.

27. (b) As regards the second point (above indicated) on which I think there is great need of fuller information, and for which records are now lacking, it seems sufficient to point to the fact, that in the great occupations for married women as laundresses and charwomen, it is at present quite impossible to arrive at either the infantile death-rate or the birth-rate. This is the more regrettable because in several very important features, such as excessive temperature, humidity, over-pressure, straining nature of parts of the work, the influences likely to be adverse to child-bearing women, are found as much in the laundry industry as in the cotton industry. Both these industries of laundry work and charing are naturally refuges for semi-skilled or unskilled working women pressed out of other trades.

28. It has been impossible with the limited staff available to attempt any personal inquiry into the question of the extent and effects of employment of mothers in laundries, though much that would throw light on the whole problem would doubtless be found by such inquiry in West London (especially Acton and Hammersmith), South London and Brighton, and other watering places.

29. As regards the physical conditions to which the women are subject in the various industries under review, reference made to the table of hours of legal employment (already furnished to the Committee) will show the daily and weekly limit of hours permissible. Although legally more hours may be worked in the pottery processes than in textile processes, actually far shorter and easier hours obtain in many non-textile factory processes (but particularly in earthenware and china works), than in either cotton or jute mills. The highly organised conditions, and extraordinarily costly, specialised machinery in these textile trades mean first a far greater pressure as to output, secondly, more heat and noise, often more difficulty as to ventilation; further either dust or humidity is inseparable from certain of the processes.

30. As to the general effect of these conditions on the health of the women and their children. Miss Squire for Lancashire, and Miss Paterson for Dundee report similarly:

That it is the employment of women from girlhood, all through married life, and through childbearing that impresses itself on the mind ... that it is useless for any medical men and others not familiar with the conditions of mill life there to pronounce any opinion on the effect of factory work upon the mother and infant; they have no

*The exact figures on which to calculate percentage are not published, but could be obtained from the Registrar General if needed.

[page 124]

conception of the stress and strain and of the general conditions of life and work in these mills.

31. Miss Paterson expressly points repeatedly to cases -showing that it is the stress and strain of the work, and the necessity of maintaining a high standard, coupled with decreasing physical capacity of the child-bearing woman under such conditions that generally determine the moment when the manager in a jute mill sends her home; sometimes (as in one of the cases under Section 61 about to come before the magistrates), the woman is sent away to go into another equally unsuitable occupation as charwoman or house -scrubber or as a home sack-sewer. Sometimes a neighbour will take the place in the mill of the woman who has been sent home on account of her physical inability to maintain her output, in return for her taking charge of that neighbour's children for a small sum.

How they live during the period of absence is a mystery, but I find that the tradesmen give credit to a surprising extent, and rents are allowed to get much into arrears. ... Great harm is done and suffering occasioned to the women by their remaining at work too long before confinement, as well as by their returning too soon after it. Factory managers, doctors, health visitors, and workers themselves are agreed that the four weeks' absence is often shortened to three or even less. I have found that a considerable number of the mothers nurse their babies regularly and continue to do so, but this natural food is always supplemented by other given without knowledge.

32. Miss Paterson personally investigated the cases of 267 mothers of young children employed in the mills, bat feels that the information given by them as to precise length of time away from the mill is not sufficiently reliable to be tabulated. As to the effects on health, moral and physical, both of the mothers and children, she was able to form very definite ideas of the excessive and injurious strain on the mothers and of the lack of sufficient care of the children. Visits on Saturday afternoons to the homes showed that any energy that was left over by the week's work in the mill was spent by the mother in family washing and house-cleaning, but dirt and discomfort abounded, and she "never saw any attempt at cooking". She sends me particulars of 144 cases where the health visitors recently found two, three or more very young children left alone in the house (in some cases locked in), while the mother was at the mill, with only such food as the mother could prepare overnight or in the early morning before leaving. Definite arrangement with another woman to take charge of the children seems far less common in Dundee than Miss Squire found in Lancashire, or Miss Martindale in Hanley and Longton.

33. Miss Squire and Miss Martindale send me information, but incomplete, of the time of leaving off work before and after confinement. The former tabulates the information in the case of Preston as follows:

PRESTON

Time of leaving off work before, and of resuming work after Confinement in the case of 124 women employed in the Cotton Mills

34. Miss Squire believes that the usual practice is for the mother, particularly if a weaver, to return to work directly the child is four weeks old, or as soon as she can obtain employment; that although in the last twelve months the majority of women remained absent two to three months, slackness of trade and difficulty in obtaining employment was given as the reason. Two of the doctors with whom Miss Squire conferred in Preston attributed the large number of premature births to continued work in the mill during pregnancy, and all considered that an exceptional number of cases of uterine trouble existed and was attributable to too early return to work. For reasons already indicated there is no centralised source of statistical information about such cases among cotton operatives. The doctors in Blackburn mention that the evil of employment of women during pregnancy is aggravated by their desire to earn as much as possible during the time before they are forced to give up work. Miss Squire herself received complaints from the women of the hardship of being discharged by the manager four or five months before confinement. She found that it was the general practice of the Preston women to nurse their babies at meal times, and before and after the day's work in the mill. In Burnley this, she found, was exceptional, while greater ignorance and unintentional cruelty in the giving of unsuitable food to the infant seemed to be common.

35. Turning to the conditions and effects in Hanley and Longton, Miss Martindale reports on the large proportion of women employed in what may be termed light work such as gilding, painting, burnishing. Many are, however, employed in "fairly arduous" work in hot and dusty surroundings. In none of the processes are the hours so long as in textile districts, seldom exceeding, often less than, the limits of 8 or 9 a.m. to 5.30 or 6 p.m. (less one and a half hours for meals). In many cases women are employed not more than four or five days a week, and intervals of easy leisurely work are possible where so much is done by hand. The usual practice is to continue work until within a few weeks of childbirth; in a third of the cases questioned Miss Martindale found absences of from five to twelve weeks beforehand. More than two-thirds of the women questioned returned to work six weeks or longer after childbirth. In one case only was return found to have taken place before the four weeks' limit. Miss Martindale found that in all the cases she investigated the women were doing their housework at the end of two weeks. For the same reason as in the Lancashire towns (lack of maternity hospitals or charities) little systematic information as to the immediate effect on the mother's health is to be had. Miss Martindale conferred with doctors and interviewed district nurses and midwives, and found little evidence of ill results. She found, however, that 38.4 per cent, of the children born to the mothers she questioned had died in infancy; this she attributed to improper feeding due to "appalling ignorance and objection to being taught". Even though partial nursing by mothers of their infants is general (and only one -seventh of the comparatively small number of cases investigated was the feeding entirely natural) an almost complete absence of cow's milk by way of supplement was noted. "Boiled bread with butter and sugar" and arrowroot biscuits seemed to be the usual supplement to the mother's nursing. The undersized, unhealthy appearance of the children that survive infancy, and the large number of cripple children in pottery towns Miss Martindale traces to diet of the kind named. She traces the larger number of cases of death from respiratory diseases and bronchitis among infants to the habit of overheating dwelling and bedrooms. Coal is cheap in the district and the workers

[page 125]

are accustomed to high temperature in the workrooms. Infants are taken without any extra clothing from over-heated, ill-ventilated rooms to the doorstep by mothers as well as the paid nurses who are somewhat systematically employed. Miss Martindale made inquiry as to the methods of the nurses among competent observers (including the Inspector for Prevention of Cruelty to Children) and the lady sanitary inspector), and could not hear that they took less care of the children than the mothers.

III. CIRCUMSTANCES AND CAUSES OF EMPLOYMENT OF MOTHERS

36. The circumstances under which the mothers leave their infants and young children to go to the mill or factory have already partly appeared under I. and II. above.

All three Inspectors have systematically directed their inquiries towards making clear the reasons which prompt early return to work after confinement as well as late continuance at work before confinement.

(1) Classification

37. I classified for their inquiry the possible reasons thus:

(i) Death of the father or lack of employment, or insufficiency of the father's wage.

(ii) Desertion by the father.

(iii) Fear on the mother's part of the loss of future work in the factory.

(iv) Preference for factory over domestic work.

Some of these reasons themselves would be effects of a concentration of a women's large industry in a district where there is absence of men's occupations, such as is spoken of above. In so far as they are effects of large economic and social causes, not immediately alterable, attempted mitigation of the results of employment rather than attempted diversion on any large scale of the employment of mothers appears most likely to prove effectual, and to be attended by fewest counterbalancing disadvantages.

(2) Summary of Causes in Cases observed

38. In case of each mother visited the Inspector has noted in schedules (giving also other circumstances) information if obtainable as to the reason for continuing and returning early to work in the mill. In the great majority the case falls under one or other of the three points in Class (i). In Dundee Class (ii) shows itself frequently. Classes (iii) and (iv) appear least of all. Detailed evidence can be given by the inspectors.

(a) Dundee

39. Miss Paterson says that when she drew the attention of mothers, who had returned within four weeks to work, to the law, they -

Admitted that they knew, but asked helplessly 'what could they do?' Poverty was in all these cases the reason for the early return, and that is practically the only reason in Dundee ... due to one cause or another, for fear of loss of work does not affect the mill operative there; if she does not get back to her own place there is so much irregularity of employment that her chance at a gate is quite a good one, and for some years there has been no difficulty in finding work. In reply to my enquiries as to absence before confinement, I found that only one of the six cases of return within four weeks after confinement had not been absent at least a month before; while there are exceptions, this is much what I have found general amongst the mill-workers ... They leave less often on their own initiative than because they are sent away to make room for a more efficient worker.

(I have already quoted Miss Paterson's experience that this dismissal in Dundee often means merely transference to another occupation, say as "scrubber".)

There has been a great scarcity of employment for men recently in Dundee, but unwillingness to work must in some cases be a reason for the man's idleness; 'slackness' was, except in a very few cases, the reason given by the woman. ... Of the mothers of illegitimate children seen, I only found one who had been since married to the father of the child, and in most cases no contribution was made by him. It is not surprising that an early return to work seems to the mother a necessity in these instances. ... Very little preference for the mill to the home was expressed among the women, the few who said they were dull at home were women without any children ... in a number of cases the worker has said of the relative or neighbour who looks after her children: 'She can keep them better than I can, she has not been brought up in the mill.' ... There is little employment for men in the mills, a certain number of labourers and carters are employed at wages from 14s. to £1. Assistant overseers do not get more than £1, and a great deal of labouring work in the mills as well as in the boat yards is paid at from 15s. to 17s. a week. ... Women's wages, in the preparing processes, are from 9s. 6d. to 12s. a week; spinners earn 11s. to 15s.; winders and warpers about 15s.; weavers, 16s. to £1. ... When a man and his wife are working in the same mill, as they so often are, the woman is probably earning the higher wage. The Inspector of the Poor in Dundee stated that the past winter has been a very bad one for working men. The shipyards have been been practically idle, the building trade, after great activity, almost dead, and there has been a long strike amongst engineers. ... Not only skilled workmen but labourers, whose earnings do not exceed £1 a week, were out of employment. It is the latter class who become the husbands of the millworkers. when these do not marry in the mill, and any 'slackness' of work soon renders them destitute.

(b) Preston

40. Preston resembles Dundee, but is even more striking in scarcity of employment for men. There are no iron works or collieries, as there are in Blackburn and Burnley. Miss Squire says:

The men are said to look out for a wife who is a four-loom weaver, and they have the reputation of being lazy.

Miss Squire herself found that the husbands of cotton operatives visited were chiefly employed as labourers in intermittent work, while "in all cases where the husband was in regular employment as weaver, platelayer, painter, bricklayer, etc., the one wage was insufficient to keep the family in the standard of life they expect."

41. In the textile mills nearly twice as many women are employed as men. Ring spinning, in which women are employed, is being gradually substituted for mule spinning in which men work.

One large firm, employing 1,442 women, told me that ... being unwilling to turn the men out of employment they had offered to teach them ring-spinning and then give them the same wages as on the mules ... the men tried it for a time and then gave it up. ... Except for heavy work such as sheetings, where the weavers are entirely men, women are preferred as weavers. The men seem to look down upon the occupation for themselves. The wages for weavers are the same whether men or women.

42. In one-third of the cases of early return to the mill investigated by Miss Squire in Preston, the reason was poverty due to insufficiency of the father's wage, and in two-fifths of the cases it was due to that and lack of employment combined. In three cases visited the mother was unmarried. In only one case was preference for mill-life expressed by the mother. The wage of the husband found to be insufficient in the cases investigated ranged from 16s. to £1. The wages of the wife, if a weaver, range from 20s. to 25s. net, if a ring-spinner, from 18s. to 25s. (recently on short time the wages have been less). While the medical men advocated, in speaking to Miss Squire, a three months' absence at confinement, both on account of the mother and the child, they considered it would be impracticable to enforce it, as the mother was in most cases "the chief wage-earner". Miss Squire visited, amongst the others, nine mothers of young infants, who were doing their best to remain at home for a time, but some of these feared they would have to go back to the mill soon. Miss Squire says:

[page 126]

I do not think that in Preston an extension of the legal time during which a mother is compelled to remain away from the factory after confinement would tend to diminish the employment of married women, and this opinion is that of trade union secretaries.

43. I am much struck in Miss Squire's notes on Preston by the number of times (as contrasted with Dundee) the entry appears, "nice, clean, comfortable home", "superior, tidy home and persons", and by the much rarer cases of illegitimate births. Even in those cases the standard of living appears higher, as may be seen from the following:

E. B. - Single, weaver, young, neat, nice-looking girl in tidy home, with parents. Baby aged ten months, healthy looking. Left work six weeks before confinement and does not mean to leave baby yet.

44. The number of illegitimate births, while far below that of Dundee, shows much less unfavourably than there the character of the people, because subsequent marriage of the parents is frequent in Preston. Another significant point in Miss Squire's notes is that the high infant mortality occurs where the number of children born to the mother is large and in rapid succession. The following is a typical case:

Mrs. B. - Husband a labourer, herself a weaver with 18s. a week. Has had thirteen children very quickly, buried nine. Baby seven weeks old out to nurse (visited, clean and neat). Breast-fed at meal-times, milk and water between. Premature birth at seven months. Pneumonia, measles, convulsions were the causes of death of the majority of the children (ages six weeks to two years). Cause of mother's return to work, poverty.

Another case shows the reason for early return to work:

Mrs. A. - Husband fireman at factory, short time twelve months, full time wages £1 a week; herself a weaver, 18s. but 10s. short time; has had eight children and buried four; eldest living sixteen years, youngest one month. Returned to factory after twenty-six days on account of poverty, due to slackness at mills; confessed to having told manager it was five weeks since confinement when it was three.

(c) Blackburn

45. In Blackburn more women absolutely but not relatively to the men are employed in textile factories; there are also more other occupations, such as engineering, for the men, though not to the extent that in normal conditions leaves a large proportion of women (and particularly married women) free to devote themselves to domestic life. Miss Squire found that while "preference for mill life" is the reason given by philanthropic workers and others of experience for the early return of mothers among textile workers after childbirth, the mothers themselves -

Generally explained to me that one wage was not enough to bring up a family upon, and that the husband would have his 'spending money' whatever the household needs were, and therefore the mother's wage, over which she had control herself, came in handy. ... The general opinion among those best qualified to judge seems to be that the working classes are well-off, and that if it were not for the proverbial improvidence of the cotton operatives there would be no poverty. Still it seems to be the practice for the women to continue their work in the mill as near to the time of confinement as the manager will allow; always the same complaint was made to me by the manager that he had to keep watch and tell the woman that she must cease work.

46. Miss Squire found that in the case of 234 births registered in 1903 both father and mother were weavers:

One would not be surprised to find their children weakly. Probably last year these families would be in poor circumstances, both parents being dependent upon the cotton trade. The men employed in the cotton industry favour restriction being placed upon married women's labour; I received many suggestions on this point.

47. The tendency of the number of women in spinning to increase is the same in Blackburn as in Preston, owing to increase of ring spinning at the expense of mule spinning. Miss Squire finds a high standard of life in Blackburn among textile operatives, comfortable houses and money to spend on excursions, holidays and amusements are considered essentials. She heard adverse comment on the number of weavers and winders, wives of tradesmen, or of men earning good wages, continuing to work and to leave their children to the care of paid nurses or housekeepers. Still she actually found, on visiting at home seventeen weavers, not specially selected, that seven were after several months at home with their infant "not returning"; one was unmarried and likely tO' return, and the remainder had returned to work because the husband had died, or was out of work or on short time. In one case the mother returned after a month when the father was earning 23s., and the two eldest children 7s. 3d. between them. The mother's return, brought in an extra 20s. a week.

(d) Burnley

48. In Burnley cotton mills the women out-number the men by nearly a third, but there is rather more employment for men in collieries and iron works than in Preston. The standard of life, the sanitary conditions in the houses., and morality, Miss Squire finds lower than in Preston. The illegitimate birth rate is higher. Miss Squire says that the impression produced on her in Burnley, and that it received support from medical men -

Is that the infants are of a miserable, debased, type in a large number of cases. Whereas in Preston, the important point seemed to be that the infant should be properly fed, in Burnley it seemed as if no amount of nourishment could build up a healthy child.

The housing conditions are worse, and in some ways conducive to immorality.

49. The notes on the few homes Miss Squire had time in Burnley to visit are painful. Poverty and desertion are the causes of the mother's early return to work. In one case the husband, a blaster, had been injured and could not return to work, so the woman had the whole family to support. In one of the two cases "where the mother was not returning to work, it was because she was dying of phthisis, and had worked "as long as she could stand", her husband, a collier, being out of work. She had had seven children, and buried two; the baby, three months old, was injured at birth, no doctor or midwife having been present; the previous infant died from neglect in the same circumstances. In another case, where the mother stays at home, the husband is a collier with good wages, and the wife had ceased weaving since marriage; this, however, did not apparently improve the chance of life for the infants, as she had had twenty and buried sixteen, all having died between one and eleven months of age.

(e) Hanley and Longton

50. Miss Martindale summarises her information on the reasons for the employment of mothers and early return after child-birth as follows:

In order to obtain some reliable facts with regard to this important matter, I questioned sixty-two women, concerning their husbands' employment, and the reasons which prompted them to seek employment outside their homes, with the following results:

| Husbands in regular work | 24 |

| Husbands out of work or working irregularly | 25 |

| Husbands delicate or in an asylum | 3 |

| Husbands dead | 4 |

| Husbands deserted them or separated | 3 |

| Unmarried mothers | 3 |

From the above it is evident that thirty-eight women were obliged to work; of the remaining twenty-four women fourteen had stated that they worked in a factory because either their husbands' wages were insufficient to allow for any additional comforts, or they desired to save while able to work, or they wished to be able to maintain an aged mother or father. Ten women were not actually obliged to work, but found the additional money very helpful.

The lack of employment for men in this district appears to be serious. The master of the workhouse informed me that a short while ago forty able-bodied and carefully selected men were allowed to take their

[page 127]

discharge for from two to seven days, in order to seek for work, their families meanwhile remaining in the workhouse. By the end of the week all the men had returned, not one having been able to find work.

From my investigations I have come to the conclusion that in very many cases the early return to work is prompted by necessity. It does not appear to me that the fear of losing future work in the factory plays an important part in the question. This may be owing to the fact that the gang system which prevails on the 'pot-banks' provides a large number of employers for women beyond the actual occupiers of the factories, and also owing to the neighbourly kindness which is so great a feature throughout this district, the women have no difficulty in procuring a neighbour to 'locum' for them during their absence.

It is impossible, however, not to be impressed by the universal preference amongst the women for factory over domestic life. I was continually being told how greatly they preferred their work in the factory to the minding of children, and how depressed and out of health they became if they were obliged to remain at home. Surprising as this appears at first, it becomes less so on consideration. At thirteen years of age the majority of these women would have begun to work in a factory, to handle their own earnings, to mix with a large number of people with all the excitement and gossip of factory life. They would thus in most cases grow up entirely ignorant of everything pertaining to domesticity. After marriage, therefore, it is hardly probable that they would willingly relinquish this life to undertake work of which they are in so large a measure ignorant, and which is robbed of that all is to them pleasant and exciting. Until as girls they have been taught to find a pleasure in domestic work, and until there is a greater supply of healthy and suitable recreations and amusements in the reach of all women, to counteract the prevailing squalor and gloom of these pottery towns, it is useless to expect them to relinquish factory life.

My attention was drawn to the fact which doubtless has to be faced, that the result of restricting married women's employment will be a decrease in the marriage and birth rates.

I was interested to find from conversations with working women and men, and others, that (1) the opinion prevails that as parents they have not done their duty unless they have seen to it that every girl as well as boy is provided with a trade; (2) that a woman is looked upon as lazy unless she takes her share in contributing to the family income. In Staffordshire the men and boys appear to willingly do their part in the domestic work of the house, and it is no uncommon sight to find a man cleaning and sweeping, caring for the children or even putting them to bed, on the evenings when the women were engaged with the family washing.

51. Miss Martindale analyses at length the occupations of mothers of illegitimate infants, and points to the large proportion occurring among pottery workers. As this forms an important factor in the problem of support of the mother I summarise the information as follows:

Illegitimate births 1902

| Longton | Hanley |

| No occupation | 11 | 16 |

| Pottery workers | 67 | 53 |

| Other occupations | 14 | 22 |

| Totals | 92 | 91 |

In these towns as in Preston, marriage of the parents frequently follows, or just precedes, the birth of an infant.

52. Some particulars on lines similar to those given above of the time and reason for early return to work, are in part accessible, or will shortly be accessible, through the help voluntarily given by health visitors in other towns, in the North of England. So far as I have seen them, the facts are very similar both as to causes of early return and effect of occupation. Only one instance of "preference for factory work" by the mother appears.

53. The forces to be reckoned with in any legislative attempt to alter the present withdrawal of the industrial mothers from domestic life seem to group themselves as follows:

1. The enormous practical difficulties attending the drafting and administering any sort of legal prohibition of employment of child-bearing women. (See in addition to the information in the first division of this memorandum, the press notices of the recent prosecutions in Preston and Dundee.) It is clear that the existing Section 61 of 1901 (and its counterpart in the Act of 1891) has been ineffective as a prohibition even though it extends only to one month. It may have had some indirect effect as a standard in the minds of those willing to be guided.

2. The existence of a considerable number of unmarried mothers without means of support other than their own labour, whose main chance of rescue from degradation lies in the very fact that they desire to labour and know they ought to labour to support their infants.

3. The presence in certain populous industrial districts of a large proportion of married mothers, who are necessarily the chief bread-winners of their families, if those families are to come into existence at all. (There is no doubt that large parts of the cotton industry could not maintain the same standard or be successful without women's labour.) This necessity as regards child-bearing women can apparently only be met by a balanced development in the same centres of men's industries.

Some attention should be given to the strength of the forces of sentiment, constitution, and character, which practically universally secure that the entire earnings of a working woman go to her family. While, no doubt, the girls and young women often spend a good deal on clothes, the married woman who works for "spending money" for herself, apart from her family, is, at present, so rare as to be negligible.

4. If married women should be against their own will and judgment compelled to forego 18s. to 20s. or more a week (see wages above) of the family income for many months, the allegation that there is increasing use of unlawful means to prevent child-bearing in some of the towns mentioned would have to be further considered. Some of the notes on bad influences in Burnley refer to the presence there of this debasing and disintegrating factor*. My attention has also been called to its presence in Nottingham, Leicester and elsewhere.

5. Although Clause D, (see above), preference for factory life, seems negligible as a motive for leaving an infant while only a few weeks old some consideration must, no doubt, be given to the spinner or weaver's natural tendency to take pride in her trade-skill and greater ease in doing work for which she is trained and fitted than work for which she has never been trained - (though she might have been trained if this had ever been adequately thought of as part of national policy).

IV. MEANS AND AGENCIES OTHER THAN PROHIBITION

54. Turning to the existing means and agencies other than prohibition of employment for enabling mothers to devote themselves to their infants the first claim for consideration seems to be made by the infants of unmarried mothers. It cannot be too clearly borne in mind that these mothers, are discharged from the workhouse infirmaries after their confinement before the four weeks limit in Section 61 is complete. I have never heard of any case where they are kept longer than a fortnight, and I am informed that the time is sometime less. Ordinary voluntary maternity charities are, as a general rule, although there are exceptions, closed to mothers of illegitimate infants, as also Charity Organisation Society aid. This may or may not be expedient, but there can be no doubt that such facts make prohibition of employment of the mother the most serious remaining injury that can be inflicted, unless some suitable organised means of support can be devised. It is not always the worst of these women who decline to enforce a claim for maintenance, or who are unwilling to stay in the workhouse. There are very few voluntary rescue homes or "penitentiaries" in England where the

*It seems to be my duty to mention that complaints in London have been made to me, and sustained, that girls are employed in the manufacture of articles to prevent conception. This employment is not illegal in England, and official efforts to persuade the manufacturer to discontinue such employment have not succeeded.

[page 128]

mother is allowed to keep her infant with her. So far as I have seen, incomparably the best results are obtained in those homes where this is allowed or organised. I learn recently from an American lady of great experience in such work in the United States, who came over to learn what she could here, that, in our neglect in England to use that essential method, and in the lack of effective trained government control and supervision of those institutions we are far behind the work that is being done in the States.

55. Leaving this special class aside, and looking at the position as a whole, general neglect of the possible voluntary agencies for helping mothers before, during, and after confinement, to take care of the infant life is the chief impression gathered. In Lancashire, where insurance of all kinds abounds (including infant life insurance), Miss Squire was unable to find any form of Provident Society to which women expecting confinement could contribute while still able to earn wages. I believe it was established at Mulhouse that organisation of a maternity fund by manufacturers, to which both employer and employed contributed, resulted in a reduction of infant mortality by half. Whether by local trade effort or larger national effort, provident insurance of the kind might be expected in time to eliminate the present grave number of cases where infant lives are lost to the State at birth, and needless suffering caused to hard-working, valuable mothers by total absence of skilled attendance.

56. Miss Squire found in Preston and elsewhere a local "Ladies' Charity" of a languishing, antiquated character, "for the relief of poor married women in child-bed". She found in the case of one that -

Since its foundation in 1811 the number of cases relieved annually has decreased from 300 or 400 to under fifty, although the population has increased so enormously. Last year, a time of special poverty ... only forty-five mothers were assisted. ... The Secretary was unable to explain this except on the ground that there was very little poverty. The relief given takes the form of medical aid, loan of requisite changes of linen, four ounces tea, one pound sugar, one pound barley, four loaves of bread, one yard flannel, and one pound soap.

57. It is evident that such charities must be fundamentally reorganised and brought into touch on the one hand with increased scientific knowledge and skill, and on the other with the changed economic conditions of the women's lives, if they are to serve their original purpose. The highly-skilled and strenuous cotton operative, with her invaluable sense of personal dignity, can no longer be helped in her heavy double work, as mother and as mainstay of a great industry, by old-fashioned charities. "Give her of the fruit of her own hands".

58. In Dundee there is a maternity charity hospital, which expressly excludes distinction between mothers married and unmarried. In that town one of the chief problems seems to be desertion of the mother.* Miss Paterson found over 100 cases in twelve mills, only among the married mothers, and these did not include the cases where the husband lived apart, but contributed something to the mother's support. Very often the wife seems to be left with the whole burden of keeping the family, for little reason except that she is capable of doing it.

Owing to the absence of the mothers in the mills, there is less opportunity for district or other philanthropic visiting in Dundee than other towns, and little information to be gained through these channels. ... The extensive employment of women with home duties

is a matter, Miss Paterson reports, which in the opinion of a member of the Social Union is making all social effort ineffectual. I have so far received no information whether effort has yet been directed in Dundee towards organising provident insurance of bread-winning mothers for the time of their confinements.

59. Miss Martindale says of Hanley and Longton -

As there is no maternity hospital (with the exception of the workhouse infirmary) in the district, the women are always confined in their own home, and are usually cared for by a kindly neighbour.

60. In the majority of the towns named, the one most important step so far towards fitting mothers better to care for their infant children is the appointment under the medical officers of health, of health visitors, and women sanitary inspector's. Sanitary authorities are in this way providing for instruction of the mother in the case of every birth of which notice of registration is given by the Registrar. Miss Squire visited some houses with one of these health visitors, and was -

Favourably impressed with the effect she seemed to produce upon the mothers or nurse, as the case might be. The serious proportion of infant deaths is a matter of common knowledge in the town, and the mothers and nurses seemed to take it as quite reasonable that the Medical Officer of Health should prescribe to them what they might and might not do, and to be impressed with the fact that what their mothers did before them would no longer be allowed to be their guide in the treatment of their children.

61. All the Inspectors have reported on efforts, which have more or less failed to establish creches for the care of young children, while their mothers are at work. This failure may not be final, but it does appear as though English and Scottish mothers have an instinctive prejudice in favour of individual care by nurses.

Generally the nurse is a relation of the mother, who, on account of increasing years, has given up work at the mill. ... They rarely take more than one baby at a time, but they will take two or three children of one family. The charge, 4s. 6d. a week,† for a baby includes its food and the washing of its clothes.

62. During the recent depression in the cotton trade the master of a workhouse -

Had had a large increase in the number of older and widowed women ... no longer wanted to mind the home and children while the mother went to the mill.

63. I have already explained to the Committee my belief in the great educational work that can be done by early theoretical and technical training of the girls of this country, the future mothers, in personal, domestic, and infant hygiene. I do not mean by this that anything should interfere with or lessen their chances of having, equally with the boys, all that can be given in primary or secondary education of general training of the mind and understanding. Nor do I mean anything that would lessen the chances for able girls in the humblest classes of rising by means of scholarships to a skilled trade or to higher learning. What I do mean is that for the great masses of future citizens, whether boys or girls, the school education that has nothing to do with and throws out no "ideas" upon the main important duties and occupations of most of their lives, is bound, as education or as instruction, to be more or less a failure.

64. No one can contend, least of all those who have any familiarity with the general ways and objects of factory and workshop girls of, say, fifteen onwards at the present time, that these girls have been given a fair chance of starting life with the beginnings of understanding what they may do for their country as housewives or as mothers. Why should the vast majority of them set a high value on their own services in domestic life, or have even a faint idea that they can be of value as things are treated at present? They are permitted to have for their house-keeping (if they do not earn anything themselves) a fraction of the family income, and they may single-handed work at duties for which the highest knowledge and skill would not be too great, by the dim light of instinct and tradition.‡ And yet it would be no more irrational to try to fight a modern army with the weapons of two centuries back, than it actually is to leave untaught girls in their

*Reluctance of the mother to enforce maintenance will always in some cases be a difficulty, but some means might possibly be organised for initiating and bearing the expenses of legal steps to secure contribution from the father.

†In Staffordshire 3s. 6d.; in some towns of Lancashire 5s.

‡Such tradition as that which defends the feeding of a five weeks old baby on "bread pobbies" that is bread,, salt, sugar, and water, "put in the oven overnight to get the balm out of it".

[page 129]

separate "homes" to raise up, in the midst of all the enemies to infant and child life in our urban centres, the future citizens of our country. Some hopeful beginnings have been made; here and there a little domestic economy as an afterthought in the schools, devoted work of medical officers of health with their sanitary inspectors and health visitors in some of the towns. But who can say that adequate sacrifices in money or anything else have been even thought of, much less attempted, to enable the future mothers and housewives to be fit for their task, or to realise that it is a task to which the governing classes of the country attach any value.

65. Until we have even secured that so many infants are neither injured nor die at birth through absolute lack of skilled care of the mother, it seems strange to be planning for future battleships or future armies or talking of old age pensions, or noting with alarm the decreasing birth rate, or discussing the possibility of prohibiting the mother from re-entering the factory for three months or more. In the case under Section 61 mentioned in a footnote above, the woman was absolutely untended and alone at the birth of her child.

66. It ought not to be impossible to link together in one great national provident and protective association all the isolated, half -informed societies and agencies at work in aid of maternity and for the saving of infant life.* More than that I believe, with Miss Squire, that all over the country, but particularly in the great centres in the Midlands and the North, it needs only an organising mind and purpose to bring such a national movement into being.

67. As regards provision for technical training of the girls, one may point to what is being done for the training of teachers of public hygiene at Bedford College for Women, University of London, and of domestic hygiene at centres such as the Battersea Polytechnic. I need not enter into details or schemes here, but I would point to the striking curves facing page x of the Report of the Mosely Education Commission, illustrating the money value of technical training as compared with trade school, training, shop training, and unskilled labour in the case of men. At present the great masses of housewives and mothers are in the position of the unskilled group, and very few have even such chances as would be comparable with those of the trade-school group. What the nation needs is to sink some of its capital in work that is comparable with that of the technical school group, and then wait till those trained young women are twenty-five years of age to see the returns begin. It is not training only in the art of laying a fire or cooking a dinner, or washing or dressing a baby that I mean by technical training in domestic hygiene. That is comparable to the work of the trade school, and that we have already in a rudimentary stage, still to be wall developed, in the schools. It is domestic hygiene in the more scientific sense, as based on simple broad ideas that can be afterwards applied that I especially mean.

V. OPINIONS ON AMENDMENT OF THE LAW

68. Miss Paterson alone offers a definite suggestion as to amendment of Section 61; I have already quoted Miss Squire's suggestion of 1897 (above, on page 3).

If any amendment of the present Act were made, I would suggest that the word 'knowingly' should be left out, and the employment made illegal - so that in order that the employer should not be held responsible, 'due diligence' (see Section 141) would have to be shown when he or H.M. Inspector could charge the actual offender. I would be glad to see the re-employment at three months made permissible only on production of a medical certificate, showing that the child's health would not be injured by its mother's absence.

69. This does not touch the question of transference of the mother's services to a fresh employer. Unless some provision could be made, comparable to that of Section 73 (which lays on medical practitioners the duty of notifying certain diseases contracted in a factory or workshop), which would require doctors and midwives to report child-birth to the Medical Officer of Health, and thereupon the latter to inquire into and forward to H.M. Inspector of Factories any cases where there is reason to believe that there is return to employment before the proper time, I do not see how such re-employment can ever be controlled.