[page 4]

PART I: THE SURVEY: ENGLAND AND WALES

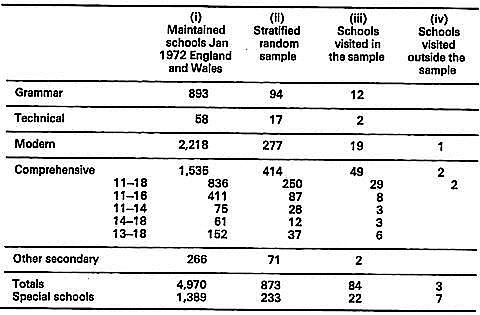

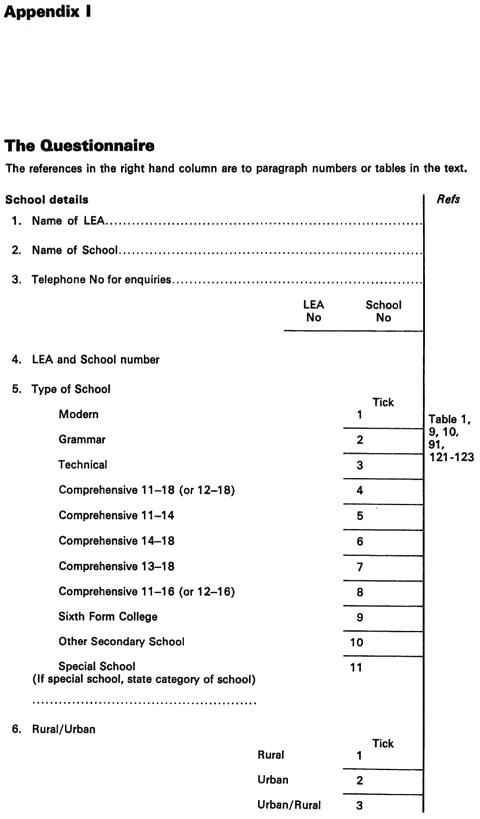

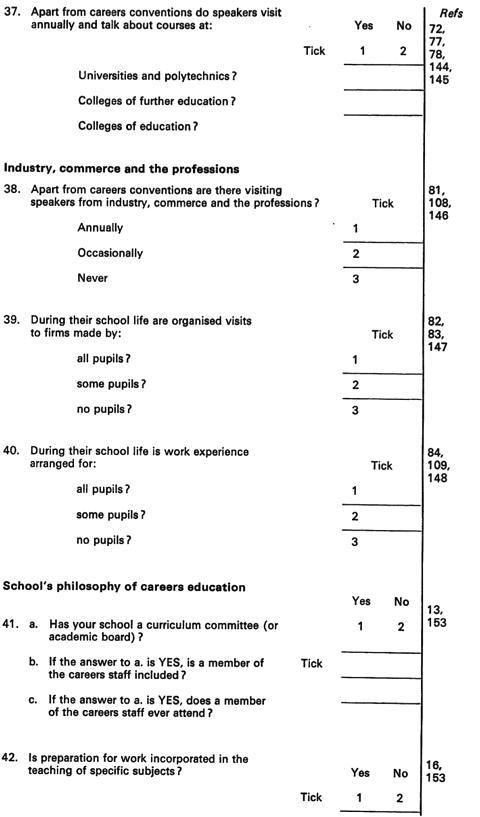

9. The survey was carried out in two phases. In the first, a questionnaire was sent to stratified random samples of maintained secondary schools and of special schools for handicapped children in England and Wales. The questionnaire (reproduced in Appendix I) was sent to all types of schools throughout the country in both rural and urban areas. Altogether, 1,175 questionnaires were sent to individual schools after consultation with professional bodies and in co-operation with local education authorities. Table 1 columns i and ii show the total number of schools of various types and the numbers included in the samples. A detailed explanation of the construction of the samples and the estimate made from them is given in Appendix II. Tables two to fourteen are estimates for the whole of maintained secondary schools other than special schools, and the answers derived from samples. The answers from special schools were not treated as part of the sample for general statistical purposes, but were used for the section on special education.

TABLE 1: SCHOOLS INVOLVED IN THE SURVEY

[page 5]

10. The response to the questionnaire, over 94%, made quantitative assessments possible; it was necessary also to attempt some qualitative evaluation. As a second phase of the operation, HM Inspectors visited 106 schools from among the samples, and also ten schools outside them.* To have used the technique of random sampling at this stage would have served no useful purpose. The schools to be visited were chosen with a view to ensuring that every type originally questioned was included. Schools were selected in such a way that HMI could visit in all parts of England and Wales, taking into account both size and type of school as well as environmental circumstances likely to influence the nature of the problems posed by careers education. In addition, it was necessary to include both mixed and single-sex institutions. (Table 1, columns iii and iv refer.)

11. In the pages which follow, an attempt is made to marry the statistical data obtained from answers to the questionnaire with the qualitative assessments made by over 150 members of H M Inspectorate working in small teams. Each team based its investigations on an aide-memoire suggesting the salient features to be investigated and discussed with headmasters and headmistresses, with members of staff, with pupils and, if opportunity offered, with careers officers and CYEE inspectors. In pages 6-36 impressions of visits to 87 maintained schools, other than special schools, are recorded; in pages 37-47 qualitative evaluation is based on visits to 29 special schools.

*One comprehensive school was visited as a pilot exercise, and the other as part of a moderating procedure. One secondary modern school was visited to ensure that the representation of this type was drawn from all areas of the country. In addition, four maintained and three non-maintained special schools in England were included to make the cover more representative.

[page 6]

Policy and practice

12. The curriculum of the secondary school responds inevitably to pressures of various kinds. It must be designed to cater for a wide spectrum of ability, aptitude, temperament and background. It must satisfy the explicit requirements of public examinations and at the same time prepare young people to take their place in adult society as workers and members of their local community. Implicit in the attitude of industry, commerce, the professions and the public at large is the expectation that the school will give every pupil a good general education.

13. In view of the varying needs and aspirations of pupils and of the claims which individual subject disciplines make on both time and resources, the planning of the curriculum is a complex business. Something over 23% of schools claim to have a curriculum committee, and the careers teacher attends as a full member in eight cases out of ten.

14. A school's policy and practice in careers education may be assessed by the extent to which three objectives are attained:

(i) to help boys and girls to achieve an understanding of themselves and to be realistic about their strengths and weaknesses;

(ii) to extend the range of their thinking about opportunities in work and in life generally;

(iii) to prepare them to make considered choices.

Of the 87 schools visited, ten are implementing a policy for careers education in its broadest sense, involving all pupils. There is no evidence of such practice in 47 of the remaining schools.

15. Achieving self-awareness, broadening horizons and preparation for the making of decisions suggest a policy to be implemented in two stages. The first stage is one of exploration - a divergent process. The second entails a convergent process leading to a decision either to continue full-time education in school or elsewhere; or to enter employment.

[page 7]

16. There is more than one way of tackling the process of exploration. One approach is to construct and treat a syllabus, for instance in English, mathematics, home economics or art, so that aspects of the world of work will be illuminated in discussion, reading and writing. Rather more than half of comprehensive schools claim to have adopted it. However, only 20% of selective schools introduce a careers element in this way. The effectiveness of such 'infusion' is found, from HMI visits to depend to a large extent on whether the curriculum is planned by a team; it also depends on the influence exercised by the head of the careers department.

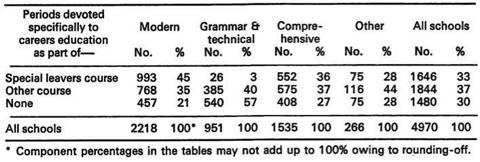

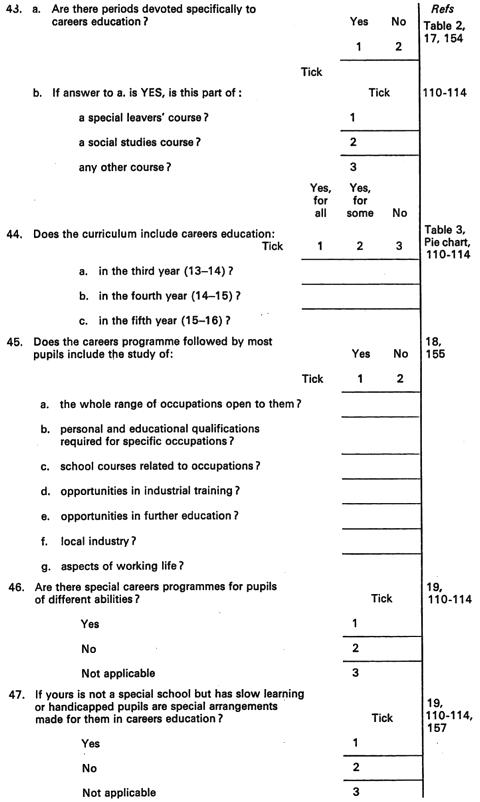

17. An alternative or additional approach is to give careers education time on the timetable. However, in nearly a third of all schools, no periods are devoted specifically to careers education. (See Table 2.) Many schools think that the most urgent need is to meet the requirements of pupils leaving at the statutory age, and the concept of careers education as a continuous process for all from the age of 13 onwards is in no sense realised. Table 2 shows that 33% of schools provide time for leavers' courses only.

TABLE 2: THE PLACE OF CAREERS LESSONS IN THE CURRICULUM

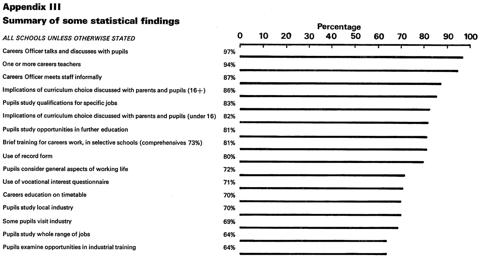

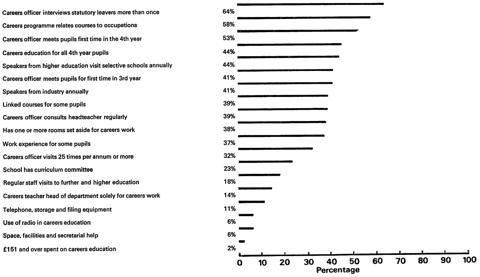

18. Asked in very general terms about the ingredients of the careers programme schools make the following claims:

| %

of all

schools |

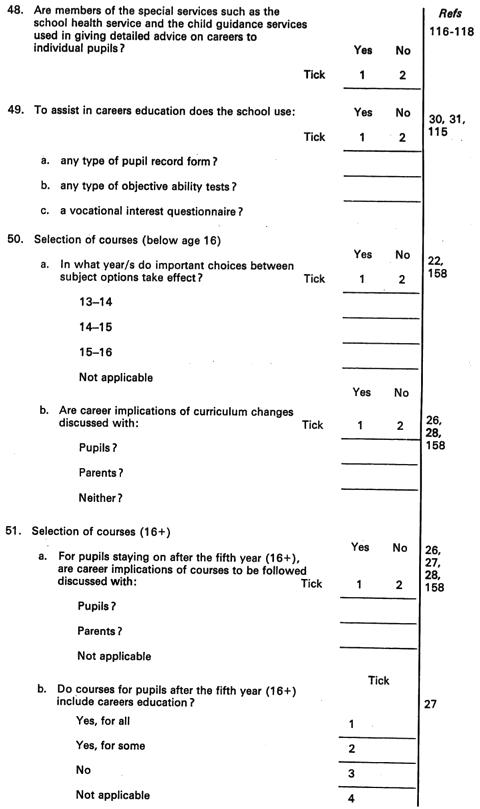

| to study the personal and educational qualifications required for specific occupations: | 83 |

| to study the opportunities available in further education: | 81 |

| to consider general aspects of working life: | 72 |

| to study local industry: | 70 |

| to consider the whole range of occupations open to pupils: | 64 |

| to examine opportunities in industrial training: | 64 |

| to relate courses in schools to occupations: | 58 |

[page 8]

At the exploratory stage it is important for boys and girls to find out about the whole range of occupations open to them, and about the opportunities that are available in further education, as well as considering specific occupations. All young people need to study aspects of working life in general and for some of them opportunities in local industry will have particular relevance.

19. Insight and experience are required to gauge the moment when an individual boy or girl begins to focus attention on one particular 'cluster' of occupations. Those who leave school at 16 must normally reach their decisions in the fifth year. For those who are continuing in full-time education the exploratory stage may last a good deal longer. To meet these varying needs and circumstances about half the non-selective schools provide special careers programmes for pupils of different abilities. In the majority of cases, however, schools (other than special schools) with slow learning or otherwise handicapped pupils do not make special arrangements for their careers education: less than one-third of them choose to do so. Clearly, every attempt must be made to overcome difficulties connected with reading and writing so that the school leaver can compete in the labour market. But it may be psychologically unsound to isolate less well endowed boys and girls from the rest of the school community so that their horizons are, as it were, limited by definition.

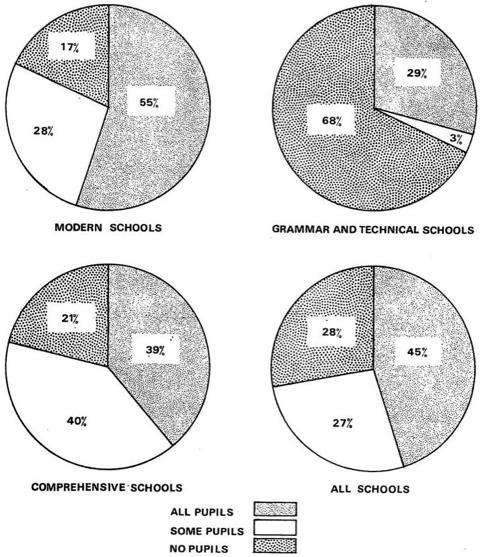

20. Table 3 gives a general picture of the place of careers education in the curriculum in the third, fourth and fifth years of the secondary school course. Overall, 25% of schools include it for all or some pupils in the third year, 72% in the fourth year and 48% in the fifth year. The statistical data about the fourth year are illustrated further in pie charts on page ten. In 64% of all schools this is the year in which the choices of subjects, made during the third year (when the pupil is 13+), actually take effect. It is also the year when for the vast majority of pupils the exploratory phase calls for the greatest care. It is clear both from the table and from the pie charts that there is no policy to which all schools conform. Where priority has been accorded to examination targets, to the exclusion of careers education, it does not necessarily imply that no individual guidance is given, but it may mean that the effect of any such guidance is considerably reduced.

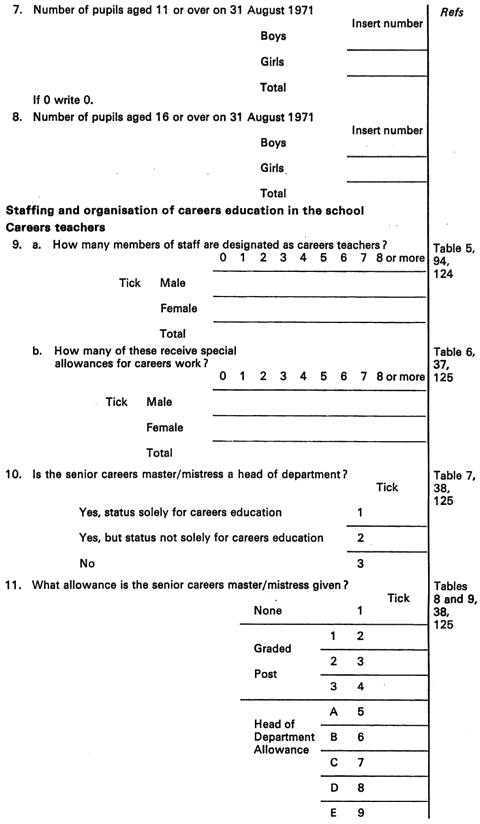

[page 9]

TABLE 3: CAREERS EDUCATlON INCLUDED lN THE CURRICULUM

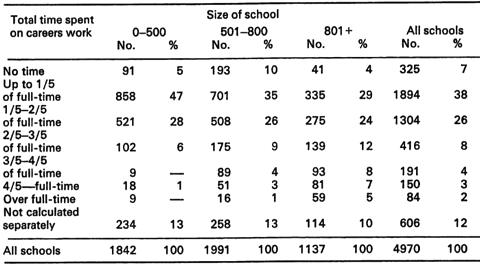

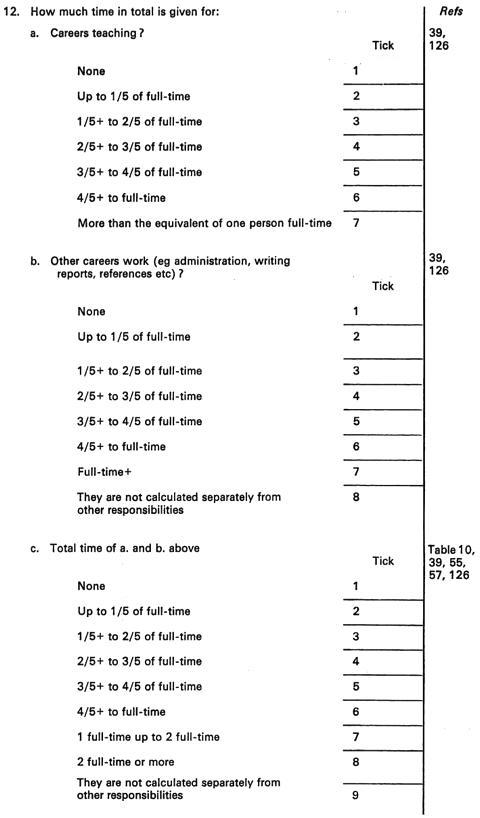

21. The state of affairs recorded will be remedied only when careers education as a continuous process is everywhere acknowledged to be an important element in the curriculum.

22. One of the purposes of HMI's visits during the survey has been to find out to what extent the curriculum, particularly after the age of 13, 'keeps doors open'. There is evidence that schools are adopting a curricular pattern which maintains involvement in language and literature, mathematics and the natural sciences, the social studies and creative, aesthetic and practical experience. Of the 84 schools visited (discounting three with an age range of 11-14), 19 still operate a restrictive pattern of options, but 25

[page 10]

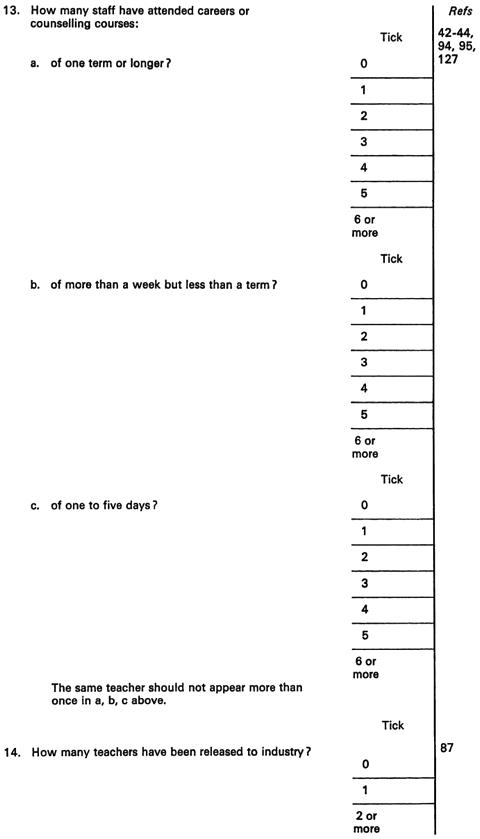

schools involve pupils in all the essential areas of study.* The general impression is that the majority of schools visited are managing to solve the problem of satisfying the pupils' wish to choose while maintaining a coherent curriculum which will allow for later changes of mind.

CAREERS' EDUCATION INCLUDED IN THE FOURTH YEAR CURRICULUM OF SCHOOLS IN ENGLAND AND WALES, BY TYPE

*In the schools visited, the great majority of pupils at the fourth and fifth year stage take a course which consists of a common core and options. The common elements are normally religious education, English language, physical education and mathematics. It is rare for a foreign language or a science to be unavailable to any boy or girl wishing to study both. The areas most likely to suffer are boys' and girls' crafts and the aesthetic subjects; moreover, it is the abler pupils who are, in general, denied adequate access to these areas.

[page 11]

Consultation and communication

23. Whatever a school does to widen horizons, the individual help available to boys and girls through personal discussion is of most immediate significance to them. They may indeed be grateful for opportunities to talk with teachers, with careers officers, with other adults or with groups of their peers; but throughout their school life they need, each of them, a personal point of first reference in times of quandary or difficulty.

24. The point of first reference in the school is usually the tutor or form teacher. When the tutor group is a unit for registration, it often numbers 30 or more, and restricted resources of staff or of space may necessitate such an arrangement. Experience of visiting schools during the course of the survey has led, however, to a conviction that a teacher acting in the role of personal tutor to a group can rarely provide an effective point of first reference for more than about 25 boys or girls.

25. Effective educational and vocational guidance depends in no small measure on consultation between teachers who act as points of first reference to individual pupils and other members of staff who share the responsibility for their work and well-being.

26. Co-ordinated teamwork is especially necessary at two stages in the secondary school course. In the third year, when decisions are reached about courses to be taken in the fourth and fifth years, the majority of schools (82%) declare that career implications of curricular choices are discussed with both pupils and parents. During the fifth year, when pupils must decide whether to enter employment or to continue full-time education in school or elsewhere after the age of 16, 86% of all schools claim to involve both pupils and their parents in discussions about the career implications of courses under consideration. Only a longitudinal study of a group of pupils could attempt to estimate the real value of such discussion.

[page 12]

27. Young people who take academic courses in sixth forms need to consult with the appropriate members of the careers team and with the careers officer, both before choosing the components of the course and during the two-year period of study. Equally, boys and girls unsuited for two or more advanced level subjects, but wishing to stay on at school, with a limited objective, for perhaps not more than a year, need similar help and guidance. Where a school possesses either a director of sixth form studies or someone of equivalent status, there tends to be better co-ordination of effort within the school to provide accurate information and helpful advice.

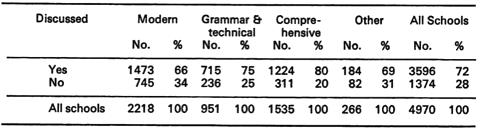

28. Parents' meetings may be used as a forum for discussing careers education. Table 4 (below) shows that 72% of all schools (80% of comprehensive schools) claim to adopt this practice. Attendance at such meetings varies widely between types of schools and between schools in rural, urban and urban/rural environments. Only 20% of schools claim an attendance of more than three-quarters of the parents; another 39% claim that between a half and three-quarters of parents are present. Selective schools enjoy the closest parental support. Figures show that schools of all types in rural areas of England have smaller attendances than the rest; this may well reflect difficulties of transport.

TABLE 4: CAREERS EDUCATION DISCUSSED AT PARENTS' MEETINGS

29. In a number of schools the greatest possible care is taken to maintain continuous contact with parents, involving them in discussions about programmes of work in school and about implications of choices made by their children.

30. The systematic recording and storage of all relevant information is essential to guidance. The majority of schools (80%) use some type of pupil record form, and 71% a vocational interest

[page 13]

questionnaire. The record form is a necessity; the vocational interest questionnaire a useful tool for those who know how to interpret it.

31. Of 87 schools visited, less than half (40) provide discernible evidence that all the essential information about pupils is systematically collected and stored for use at the proper time. About one school in five of those visited - these include schools of all types - shows an understanding of the problems involved and is tackling them with some success.

32. In some schools, documentation about pupils is impressive in its thoroughness, and reveals a shrewd but sympathetic understanding by members of staff. In such circumstances the effectiveness of the vocational guidance interview is greatly enhanced. Describing an interview in one school, HMI commented that the school had good records reflecting each pupil as a whole person, and that these had been discussed with the relevant teachers beforehand. Thus, the careers officer had as complete a picture of the pupils as the school could provide.

33. Channels of communication between all concerned, including parents, need to be clearly understood, kept open and methodically used. In 48 of the 87 schools visited, lines of communication seem to be insecure. There is evidence of a sound structure in ten schools, but only two of these possess a careers team working closely with all relevant members of staff and with the careers officer. Some schools, where careers education is rightly regarded as a team effort, reveal a lack of systematic consultation between tutors, subject teachers, the year heads and the careers team.

34. However skilfully teachers may be deployed, there is evidence that manpower resources have been over-strained. HM Inspectors have been given numerous opportunities, by courtesy of the schools they have visited, to talk to boys and girls about their programmes of work and about the individual help and advice which they have received. The comment of one girl is typical of a situation all too prevalent: 'The teachers help us as much as they can', she said, 'but the trouble is that there are too many of us and too few of them'.

[page 14]

Staffing and organisation

35. Careers education is one facet of the total process of pastoral care, and it should thus be regarded as an integral part of the arrangements by which schools seek to promote the general well-being of their pupils. The acceptance of their pastoral responsibilities is implicit in the organisation of all schools; nevertheless only a quarter of the schools visited have a system in which all the elements of guidance - personal, educational and vocational - are included.

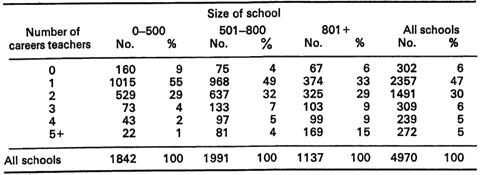

36. The vast majority of schools in England and Wales (94%) designate at least one member of staff as 'careers teacher'; 46% claim more than one teacher so designated (see Table 5 below). But the role can be variously defined. Some schools include in this category members of staff whose special concern is with personal and social guidance rather than specifically with careers guidance.

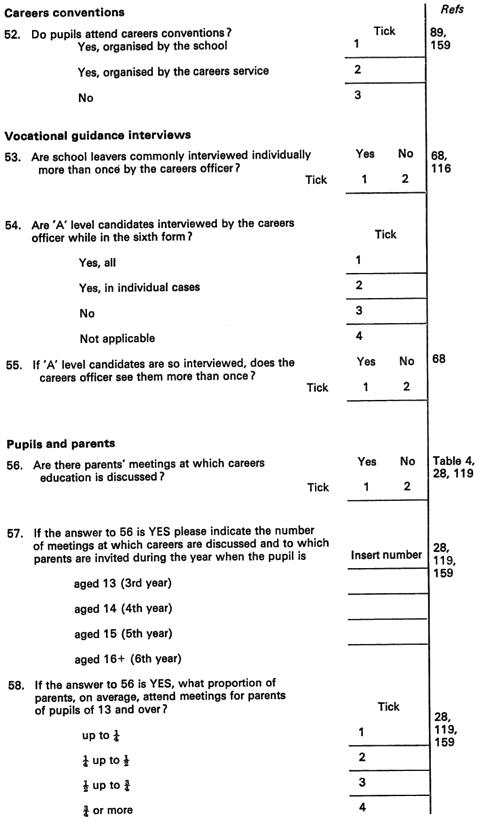

37. The careers teacher, though a familiar figure in some staff rooms for more than a quarter of a century, is rarely given the status merited by so important a task. Less than 60% of schools record the payment of any allowance for this work, and only 15% of schools pay an allowance to two or more careers teachers (see Table 6 below). Such an allowance may be paid not exclusively for careers work; in some cases the proportion that arises directly from responsibility in the careers field is small. It is appreciated that schools with less than 500 pupils on roll have less scope for dispensing allowances for separate responsibilities, and include junior high schools (11-14) in which there is less likelihood that a separate allowance will be paid to a careers teacher than in schools catering for the full secondary age range.

[page 15]

TABLE 5: NUMBER OF STAFF DESIGNATED AS CAREERS TEACHERS

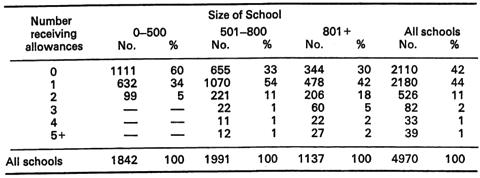

TABLE 6: NUMBER OF CAREERS TEACHERS RECElVlNG SPEClAL ALLOWANCES

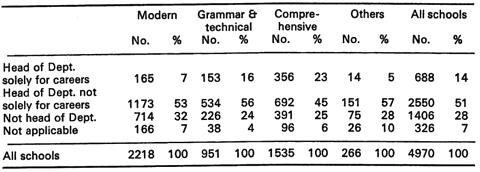

38. It is rare for a head of a careers department to hold a scale post for responsibilities undertaken exclusively in connection with this work. Of all schools the proportion is 14%; of comprehensive schools it is 23% (see Table 7 below). A scale 4 post or above is offered by less than 8% of all schools in England and Wales solely for careers work. Often this duty is combined with another major responsibility; deputy head, senior master or senior mistress, head of subject department, year tutor or librarian. (Further details can be found in Tables 8 and 9 and in the explanatory notes attached to them.)

TABLE 7: STATUS OF SENIOR CAREERS TEACHERS

[page 16]

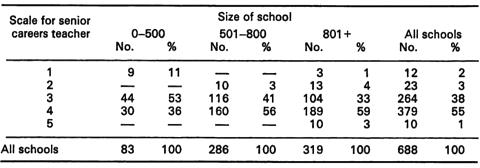

TABLE 8: SCHOOLS WHERE THE SENIOR CAREERS TEACHER lS HEAD OF DEPARTMENT SOLELY FOR CAREERS WORK: SCALE FOR SENlOR CAREERS TEACHER

(Scale operative from 1 April 1972)

TABLE 9: SCHOOLS WHERE THE SENIOR TEACHER IS A HEAD OF DEPARTMENT BUT NOT SOLELY FOR CAREERS WORK: SCALE FOR SENIOR CAREERS TEACHER

(Scale operative from 1 April 1972)

Table 8 provides an analysis of the allowances paid in the 14% of all schools shown in the top line of Table 7. Of these 688 schools, 389 offer scale 4 posts or above; this represents less than 8% of all schools in England and Wales.

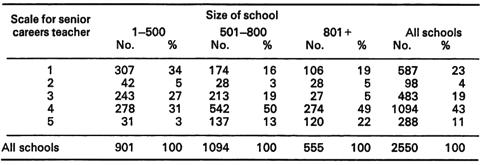

Table 9 analyses allowances paid in the 51% of all schools shown in the second line of Table 7. From Tables 8 and 9 taken together, it will be seen that in 1,771 schools (36% of all schools) careers education is directed by a senior member of staff with a scale 4 allowance or above; but in only 389 of these is the responsibility solely for careers work.

39. Schools were asked to estimate time given to careers work in the classroom, time spent on other careers work as described in paragraph 40, and the total time allotted to all aspects of this work. As Table 10 records, in nearly half of all schools, the total time allotted to careers education and guidance amounts to no more than the equivalent of one-fifth of the work load of one full-time member of staff. Many schools cannot calculate separately the time spent in careers work other than careers teaching. But only 15% of all schools record that careers teaching occupies as much as one-fifth of the work load of one member of staff.

[page 17]

TABLE 10: TOTAL TIME SPENT ON CAREERS WORK

40. In connection with the survey, a seminar for headmasters and headmistresses was held in January 1972, and members considered the role of the senior careers teacher and the qualities and experience required. Their description recognises that the role is conditioned by the size of the school, by its objectives and by its organisation; that it must allow for individual interpretation according to the personality of the teacher concerned. They list, nevertheless, certain essential responsibilities:

(i) to act as a co-ordinator, linking the curricular and pastoral care aspects of the school;

(ii) be fully involved in curricular development, and fully conversant with details of organisation and of the pattern of the curriculum throughout the school;

(iii) to ensure that certain instrumental functions are performed:

a. liaison with the careers officer;

b. establishment and control of links with higher and further education, with industry, commerce and the professions;

c. the administration of work experience schemes where appropriate;

d. the organisation of the secondment of teachers to industry;

e. supervision of the careers room and of careers literature;

f. planning the use of timetabled time designated for careers work.

They stress that if the work is to be carried out effectively, the careers teacher must be given time from other teaching duties for

[page 18]

planning, and time to take part in the in-service training of colleagues on the staff. Clerical assistance is needed to cope with routine and repetitive tasks.

41. In the opinion of the members of the seminar, a careers teacher:

a. should have had successful teaching experience over a wide range of ability and with several age groups;

b. should have the ability to develop good personal relationships and be a good communicator;

c. should have had specialist training in the field of careers guidance.

42. The survey reveals that in-service training has usually taken the form of short courses lasting from one to five days. It is not possible to state how many teachers in England and Wales have attended such courses, but the following figures show the proportion of schools that record that one or more teachers have attended a brief period of in-service training of this kind:

| % |

| Grammar and technical schools | 81 |

| Comprehensive schools | 73 |

| Secondary modern schools | 66 |

Longer courses are less common: 24% of schools record having at least one teacher who has attended a course of more than a week but less than a term; 11% claim to have at least one teacher who has attended a course of one term or longer.

43. Universities and colleges of education provide one year full-time courses in counselling. Between 1963 and 1972, over 350 men and women qualified through such courses to hold a post designated as 'counsellor'. The counsellor is an experienced teacher who has acquired some professional expertise in helping boys and girls to cope with personal and social problems either at a crisis point or over a continuous period. During the counselling process, personal, educational and vocational issues may all arise. The careers teacher, being primarily concerned with educational and vocational guidance, shares some common ground with the counsellor. There is a growing recognition of a common core in the training of a careers teacher and a counsellor; one college of

[page 19]

education is running a one year full-time course leading to a diploma in counselling and careers work.

44. Awareness of the need for specific training has grown steadily over the past decade. Initiative has been taken by individual local education authorities, and those in one region in the North of England have set up a consortium to plan the training of careers teachers. A team composed of heads, teachers, a CYEE inspector, careers officers, LEA advisers and HMI have already trained some 500 teachers on one-week courses, and some 80 of these teachers have attended a follow-up course. As part of the Department's national short course programme, a series of basic courses was followed by a further series designed to 'train the trainers' which has produced a team of over 100 teachers and careers officers who are now considered suitable to be group leaders on regional and local courses. More recently Area Training Organisations in conjunction with DES have established courses in several parts of the country; these courses, often spread over a period of two terms, are designed to provide a more thorough and systematic introduction to careers work. Other agencies are also active in the training field: the Institute of Careers Officers, the Careers Research and Advisory Centre and the National Association of Careers Teachers. The Central Youth Employment Executive has acted as a useful clearing house for collecting and disseminating information about courses.

[page 20]

Material resources

45. The operation of a realistic and effective programme of careers education in a school depends in some measure on the provision of space specifically allocated for it and on other material facilities.

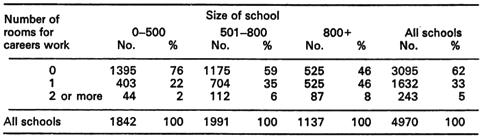

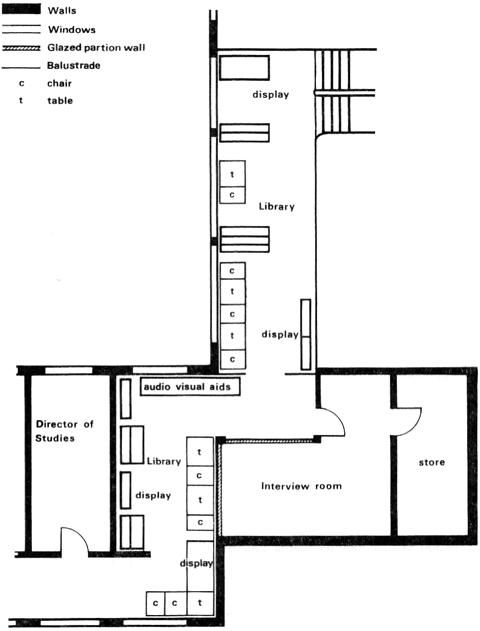

TABLE 11: ACCOMMODATION

The figures in Table 11 suggest grave inadequacy in basic provision of accommodation. Size of school has obvious relevance but no less than 46% of schools with over 800 pupils state they have no room designated for careers work. A mere 38% of all schools claim one room or more, and of something under 2,000 medium sized schools, only 6% claim two or more spaces for careers work.

46. There is a wide variation in the nature and quality of careers accommodation; it largely depends on the status the school accords to careers education and guidance. Even when this is given high priority rooms have frequently to be shared, to be used as teaching space by other departments or as offices by two or three members of staff. In such circumstances access for pupils for purposes of consultation, reference or browsing through literature is of necessity limited to certain times during the day or week. Schools have been visited where accommodation for careers education is no more than a converted stock room, space at the end of a corridor or an alcove off a passage.

47. Furnishing, equipment and general attractiveness of careers rooms vary widely. Some are spacious and light with comfortable

[page 21]

chairs, attractive displays of material and a welcoming atmosphere; others offer little in the way of encouragement to enter them. One careers room visited was previously a science laboratory and its original fixed science benches are still in position. In another, the furniture consists of a desk, two chairs and a battery of cloakroom lockers which serve as a filing cabinet. In one instance a room is nominally available to members of fifth and sixth forms, but the thick layer of dust which covers everything does not engender much confidence in the regularity or intensity of its use.

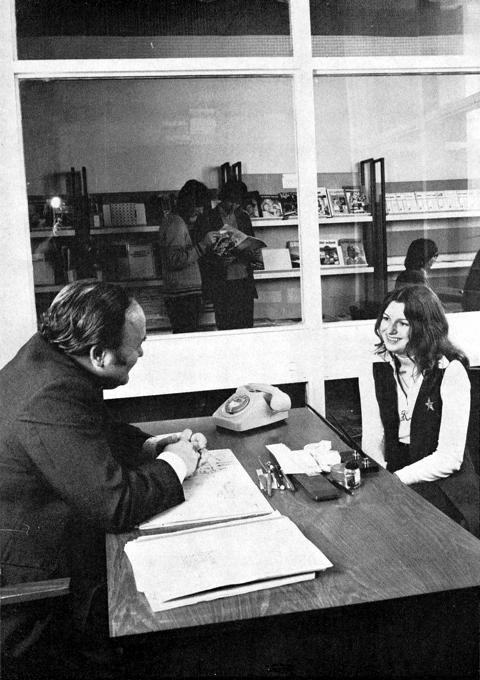

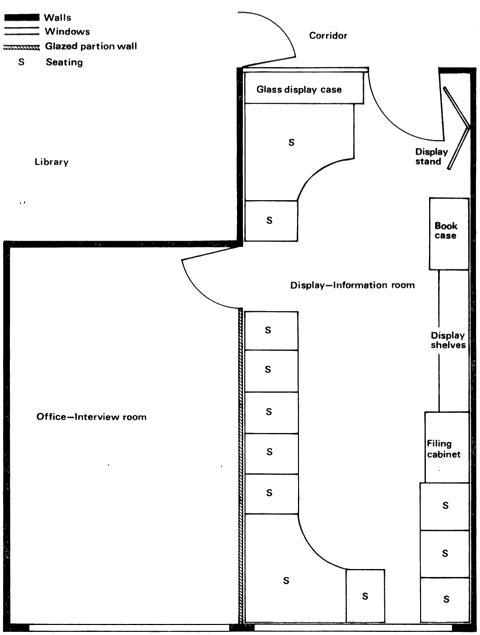

48. In contrast, a school opened in extended premises as a re-organised 12-18 comprehensive school in January 1970 includes in its extensions a purpose-built careers suite.* This consists of a well appointed office for the head of careers department, and it has its own telephone extension. A glass partition separates the office from the adjoining careers library-cum-tutorial room where careers literature is displayed on shelves along one side. The room is comfortable and inviting and tutorial groups may meet here during time-tabled careers periods. It is also well used as a reference library during breaks and lunch intervals.

49. When full tribute has been paid to what has often been achieved by ingenuity, perception and hard work on the part of heads and members of staff, the evidence of the survey, putting together quantitative analysis and qualitative judgement, points to grave inadequacy which must be remedied if more than meagre lip service is to be paid to an important element in the programme of secondary schools.

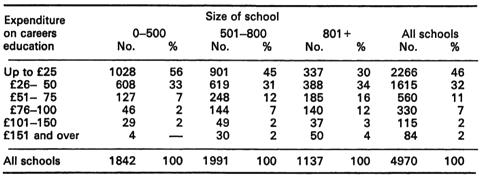

50. The varying amounts which schools spend on materials and visits for careers education are indicated by Table 12. Only 2% of schools spend over £150 per year, and it may seem surprising that only 19% of the larger schools spend more than £75 a year.

*By permission of two schools (neither of them in the stratified sample) a plan and photographs are reproduced (1) of the purpose-built suite referred to in paragraph 48 and (2) of a careers suite created by a process of adaptation (see centre pages).

[page 22]

TABLE 12: EXPENDITURE ON MATERlALS AND VlSlTS FOR CAREERS EDUCATION

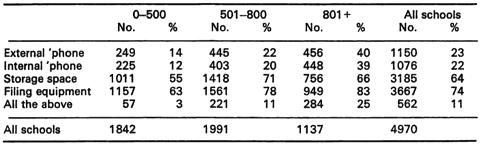

51. Table 13 summarises provision for certain facilities: telephones, storage space and filing equipment. On all these counts, 11% of schools claim to be properly equipped. Here again, the extent of the provision made inevitably bears some relation to the size of the school.

TABLE 13: FAClLITlES FOR CAREERS WORK

52. Direct and immediate communication with the outside world is always important and often essential to the careers teacher. Only just under one-quarter of all secondary schools claim to have an external telephone specifically for the use of the careers staff, and a similar proportion claims an internal telephone. Statistics not shown in Table 13 reveal the percentage of schools of varying types which have this facility:

| External

telephone | Internal

telephone |

| Grammar and technical | 17% | 13% |

| Modern | 17% | 16% |

| Comprehensive | 37% | 37% |

53. Careers literature is available from many sources, and these include the Central Youth Employment Executive which supplies to schools some approved publications free of charge. A number

[page 23]

of publishers and other agencies produce descriptive and informative material covering virtually the whole range of occupations. By no means all schools calculate per capita expenditure on such literature as a separate item; hence the evidence drawn from answers to the questionnaire can give only a rough indication of present practice. Of all schools 47% state that they spend up to 3p and a further 24% between 3p and 5p per head, while 13%, on their own admission, spend nothing.

54. On the accessibility of careers literature to pupils, evidence is encouraging for, overall, 96% of schools claim that careers publications are accessible and the same proportion state that these are available for borrowing. The fact that there are facilities for open display in only 84% of schools suggests limitation of space and not necessarily lack of initiative.

55. The mass of material available and its variety makes systematic classification essential to an effective information service, but 32% of schools undertake no such cataloguing of their literature. This failure suggests lack of time and of manpower.

56. As the concept of careers education broadens, and outside contacts become more extensive and varied, the allocation of some regular secretarial assistance is essential to the effectiveness of the careers teacher's work. At present about one secondary school in three is able to provide some secretarial help specifically for the careers department. Occasional assistance is made available through the co-operation and forbearance of heads and deputy heads, by the willingness and generosity of many hard-pressed school secretaries and by other members of staff, pupils or parents.

57. Schools were asked about their use of television, radio, films and film strips and slides. It is not surprising that 60% of schools record some use of television as a medium for careers education. By contrast only 6% of all schools use radio programmes. In view of the quality of radio careers programmes, the obvious care with which they are produced and the skill and experience of the contributors, these findings are both surprising and disappointing. Some use of careers films is made in 25% of all schools, but very few schools make use of film strips and

[page 24]

slides. Of one school it is said that such resources are seldom used partly because there are no careers lessons on the timetable to make the showing of films and film strips a practicable proposition; of another that blackout facilities in the classroom are inadequate, and films can be shown only in winter months. Indeed, in making effective use of visual aids, space, facilities, time and manpower are crucial factors.

58. Impressions gained during the visits to 87 schools in England and Wales confirm evidence obtained from answers to the questionnaire. In 51 schools there are inadequate facilities, while of the 15 schools which are better equipped than the others, only 3 impressed H MI as being well provided for in all important respects. This impression is consistent with the results of the statistical analysis which reveals that only 6% of all schools have adequate space, facilities and secretarial help.

[page 25]

The Careers Service

59. In the process of secondary education, careers officers represent, for members of staff and for boys and girls, a link with the highly complex and diversified world of work. Their expertise is threefold. First, they have access to information about possibilities of employment both locally and nationally. Second, they possess knowledge of specific occupations including those for which special qualifications are needed. Third, they develop, with training and experience, the insight, sensitivity and shrewdness needed in vocational guidance interviews.

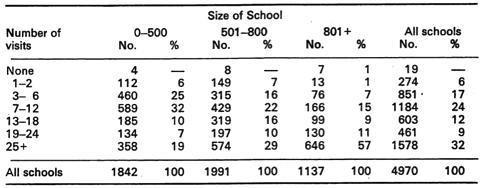

TABLE 14: NUMBER OF CAREERS OFFICERS VISITS PER YEAR

60. Table 14 illustrates the relationship between the size of school and the number of visits per year paid to them by careers officers. Size alone does not determine the number of visits which are advisable. By the same token, the number of visits indicates nothing about either the length of time spent at the school or the value of the occasion. The careers officer needs to visit the school frequently enough to be familiar with certain key members of staff, with the pattern of organisation and curriculum, and with the special problems which individual boys and girls are liable to face at crucial points in their school lives. It is unlikely that the 63% of small schools receiving 12 or fewer visits a year, the 61% of medium sized schools receiving 18 or fewer, and the 44% of large schools

[page 26]

receiving 24 or fewer, are making full use of the expertise of the careers officer*.

61. Visits to schools have confirmed the impression, gained over the past few years, that there has been a significant strengthening of the partnership between careers officers and many of the schools which they visit. The practice of regular visiting for a full day or for half a day per week is becoming more common. It is in schools which enjoy this regular visiting that fruitful co-operation has been found. Of a 13-18 mixed comprehensive school, HMI records that the careers officer spends two half-days each week in the school taking particular care to choose times which coincide with periods in which members of the careers staff are available to meet her. She also makes special visits to the school if requested to do so. To quote another instance, a boys' secondary modern school is visited at least once a week throughout the year by the careers officer who joins in group discussions and gives individual interviews to which parents are invited. Other examples include a mixed grammar school which is visited for half a day each week, another mixed grammar school which three careers officers each visit for one day a week, and a technical school for boys which is visited between 50 and 60 times per year.

62. A problem facing careers officers is that of matching their visits to the timetabled programmes of the schools. In one area a meeting is held between careers staff from all schools concerned and the careers officer, during the summer term, to arrange the programme for the ensuing year. As a further example, a mixed secondary modern school, which operates a two-week timetable, receives a visit once a fortnight from two careers officers; one of these, in addition, holds a weekly 'surgery' during a lunchbreak when pupils may see him if they so wish. This particular careers officer estimates that his help is sought by an average of six to nine pupils on each occasion.

63. About two schools in every three seek the help of the service in planning the various aspects of the careers programme, and nearly all schools arrange for the careers officer to interview individual pupils and to hold discussions with groups of boys and girls. Planning may involve suggesting speakers, films or activities

*The stratified sample contained 61 schools having over 1,200 pupils. Of these 44 (72%) record 25 or more visits per year.

[page 27]

relevant to the stage of vocational development of various age groups. It may include also advice on work, visits and arrangements for meetings with parents.

64. Consultation between careers officers and heads takes place regularly in 39% of schools and occasionally in nearly all the remainder. Contacts between careers officers and teachers, other than those nominated for careers work, tend to be informal. It is encouraging to find a few cases where the careers officer is invited to take part in staff meetings; equally discouraging to learn of a few schools where this officer has no contact whatsoever with members of staff other than with those specifically designated for careers work.

65. Careers officers meet members of staff, pupils and parents in a number of contexts. Schools report that they receive assistance from careers officers in the following ways:

| % |

| By giving talks and holding discussions with pupils | 97 |

| By giving talks and holding discussions with parents | 64 |

| In planning careers programmes | 63 |

| In planning work visits | 58 |

| In planning talks to parents | 48 |

| In planning work experience | 20 |

66. Instances have been found, however, where schools rely on the help of the careers officer not only for guidance but for all careers education. In a comprehensive school which is visited one day a week, the careers officer is called upon not only to give vocational guidance but to be responsible for all specialised work in careers. It seems hardly necessary to point out that such a practice puts unnecessary strain on careers officers, and that a school is failing in its essential commitment if it regards the relationship with the Careers Service in this light.

67. In a little over half of the schools, boys and girls meet careers officers for the first time during the fourth year (age 14+) ; in 41% of schools the meeting takes place in the third year (age 13+); and in 5% of the schools (mostly selective) in the fifth year (age 15+). There may be advantages for pupils, parents and teachers if the first contact is made during the third year. For pupils, this is normally the year during which choices of curriculum are made,

[page 28]

and it may well be that discussions with the careers officer can help a boy or girl, and maybe the parents as well, to understand more fully the implications of choices made. But there are almost certainly disadvantages in postponing the first contact until the fifth year*. By the time that the pupil meets the careers officer it may be too late to review a decision either to stay on or to leave; equally, by that time the choices made in the third year will fully have taken effect, and the pupil's chances. of reaching a wise decision be thereby reduced.†

68. Careers officers interview leavers at the minimum statutory leaving age more than once in 64% of all schools. They interview more than once pupils, beyond that age who are taking A-level courses in 26% of schools providing such courses.

69. Of 87 secondary schools visited in connection with the survey, 54 provide clear evidence that careers officers and members of staff have established an effective partnership. In 11 of these 54 schools careers officers are fully involved in programmes of careers education and in the process of educational and vocational guidance. In a further 27 schools, evidence is that all concerned are well on the way to fulfilling similar objectives. Apart from 16 schools in which the situation can be described as adequate, there remain 33 schools out of the 87 visited where contacts are tenuous and relationships have as yet to be put on a sound footing.

*References to third, fourth and fifth years respectively assume an age range of 11-18 or 11-16.

†The timing of careers education in relation to curricular choice has been considered more fully in paragraph 15 et seq.

[page 29]

Relations with further and higher education

70. Many careers are open only to those who continue with full-time education after leaving school. The school has therefore a particular role to play in establishing links with institutions of further and higher education. Of all schools, some 70% claim that members of their careers team pay occasional visits to colleges of further education or to institutions of higher education. Only 18% of schools claim to make regular visits.

Further education

71. Organised visits to colleges of further education are seldom regarded as appropriate for all boys and girls: 22% of schools do not appear to arrange any visits. Though some 30% of schools have nominated teachers for liaison with colleges, the picture drawn from a statistical analysis is not reassuring. Moreover, from impressions gained during visits to 84 schools (discounting three schools with an upper age limit of 14), 38 schools show meagre evidence of any fruitful relationships with colleges of further education in their neighbourhoods. There are six schools which take full advantage of the opportunities for co-operation and 19 others which are beginning to do so.

72. Visitors from colleges can often help schools to forge links between these two educational institutions. But nearly 60% of non-selective schools and nearly 70% of selective schools state that no arrangements are made for speakers from colleges to pay annual visits in order to talk to potential students.

73. There are, however, growing points worthy of mention, and they illustrate what can be achieved. One comprehensive school visited enjoys the services of a further education lecturer who acts as schools liaison officer and whose work is likely to help the careers staff to acquire an increasing knowledge of the constantly changing demands of industry and commerce, as well as the standards required of students entering further education at various levels. In

[page 30]

another comprehensive school which has developed excellent working relationships with colleges of further education, pupils in the fourth and fifth years visit colleges as well as places of work, and members of college staffs are among the visiting speakers invited to give talks as part of the careers programme.

74. There is evidence that a school can benefit from the initiative taken by other educational institutions. In one area visited, the principal of the college of further education and the headmaster of the grammar school have together produced a booklet outlining the courses offered by both establishments. They have paid joint visits to all schools concerned in order to talk to the pupils, and they have addressed parents at a number of evening meetings.

75. 'Taster courses' are proving valuable. Such courses are in no sense a form of vocational training; they are part of the exploratory phase during which young people see for themselves the nature of various opportunities open to them. A job sampling scheme has been established in an 11-16 comprehensive school. Candidates for CSE and GCE attend the college of further education for a number of weeks, dividing their time equally between various courses, for instance mechanical engineering, electrical engineering and building trades. A secondary modern school offers taster courses as an option in the fourth year. They are designed to give each pupil some vocational experience in an occupational area chosen from business studies, textiles, artwork and display, building studies and engineering studies. Courses such as these are most effective when they are planned jointly by members of the staff of the school and the college respectively, when the school receives from the college an assessment of each pupil's progress and when the college receives from the school subsequent impressions of the value of the course to the boys and girls engaged in it.

76. The 'linked course', whereby pupils still at school attend a local college of further education part-time, provides a more structured framework within which to plan these co-operative ventures between schools and colleges. Statistics show that some 40% of all schools and about 50% of secondary modern schools claim to make such arrangements. When successful, they can achieve one or both of two objectives: first to broaden educational experience; second, to enable boys and girls to take courses in

[page 31]

some aspects of the social sciences, the natural sciences, technology or business studies, for which resources may not be available in the school, At a girls' 11-18 school, some pupils in the fourth year spend one session a week in a college of further education learning about the work of a hairdresser. The school finds that this experience gives them added pride in deportment and appearance. They benefit also from working in an adult environment. At an 11-18 comprehensive school, a materials technology course combines aspects of art, home economics, design, technical drawing, engineering, physical sciences and biological sciences. Pupils spend one half day at the college of further education and are working for Mode Ill CSE examinations. A girls' 13-18 school arranges for members of the sixth form to study further mathematics at a neighbouring polytechnic, and for other sixth form girls to take courses in computer science, economics, sociology and Spanish at the college of further education.

Higher education

77. A visit to an institution of higher education, or a talk by a visiting speaker may provide the first direct introduction to higher education. Difficulties in the way of regular, organised visits to universities and polytechnics can be understood more readily than can obstacles which are said to prevent schools from arranging for speakers to come and address older pupils. Only 45% of selective schools and 30% of comprehensive schools make such occasions an annual event. Of the 57 schools visited which send pupils directly into higher education, 12 have established strong links and in a further 25 there is evidence of some contact.

78. Relations between schools and colleges of education appear to be tenuous. Only 13% of all schools declare that they invite speakers to talk about courses at these colleges. Many young people enter teaching from universities, and the decision to teach may well be taken at a later stage. Nevertheless, older boys and girls are entitled to know about opportunities in colleges of education.

79. Here and there encouraging signs have emerged. One local education authority holds residential courses lasting from three to four days in July in order to inform pupils in the lower sixth about courses in higher education. An 11-18 comprehensive school

[page 32]

issues to all entrants to the sixth form a bulletin giving guidance on the process of choice and decision in relation to higher education. A 13-18 comprehensive school regularly sends pupils on day visits to universities and to the college of education. Pupils attend residential courses provided by Nottingham University (for potential mathematics and science applicants) and by the Universities of Keele and Manchester for sixth formers interested in English and Arts subjects. These examples show what can be achieved when sixth form careers guidance is well co-ordinated and tackled with initiative.

[page 33]

Relations with industry, commerce and the professions

80. In 19% of secondary schools careers teachers regard the placing of pupils in employment as a major part of their duties; in 57% of schools it is considered to play a minor role and in 19% to form no part of the careers teacher's responsibility. Placement is normally best left to the Careers Service but there are clear advantages both to teachers and pupils in maintaining general and particular links with industry, commerce and the professions.

81. Virtually all schools make some use of visiting speakers. Statistics show that some 41% of schools invite a number of speakers to visit annually in order to talk to pupils. Another 56% issue such invitations on an occasional basis. There is, however, no generally held conviction that a talk by a visiting speaker provides the most effective introduction to a particular profession or sector of employment. One modern school visited, which in the past has invited speakers from industry and old boys and girls of the school to come and talk to pupils, has now discontinued the practice because it has been found that the pupils become bored and derive little benefit from such formal lectures. This school believes, as indeed does a grammar school also visited, that there is greater value in arranging for small groups or for individuals to visit places of employment and to take part in work observation. But not all schools would agree that the value of the visiting speaker should be discounted. One grammar school, for instance, has compiled a register of some 100 parents, in a variety of professions and industries, who have volunteered to come to the school to speak about their own occupations, usually to members of third forms. In some instances, visits to firms by groups of boys and girls result from a talk given by a parent. Talks by representatives of the world of work, who may be parents or former pupils, are sometimes arranged for parents, for instance through a parent-teacher association, with attendance by senior pupils if they so wish. There is general agreement, however, that the use of visiting speakers is most effective when followed up by informal discussions with pupils in small groups and, if practicable, by some form of work observation.

[page 34]

82. The opportunity to go out, to visit firms and see working conditions at first hand often provides a telling and effective experience. On such occasions boys and girls may talk to employees about their work or to training and personnel officers about opportunities which may be available. As it is, 26% of schools arrange for all their pupils to make such visits; 69% make arrangements for some pupils to do so.

83. In an 11-18 school, all groups in the fourth year are timetabled together so that some can attend a talk or film, while others go out on visits in parties of about a dozen. The aim is to promote some general understanding of a factory, office or other workplace, its atmosphere, its purpose and the kind of people who work in it. Members of staff have produced a questionnaire to help boys and girls to ask pertinent questions about rates of pay, length of apprenticeship, holidays, facilities, day release or other matters of direct concern to possible employees. Preparation for and follow up of visits are given great emphasis.

84. There are nearly 1,900 secondary schools in England and Wales (38% of all schools), in which a work experience scheme has been developed for at least some pupils. Some 51% of selective schools in urban/rural districts arrange some such experience. Careers officers assist in organising schemes for some 20% of schools; it follows, therefore, that an almost equal percentage develop their own schemes and work out their own arrangements. The Education (Work Experience) Act, 1973, will enable local education authorities to extend work experience within their discretion.

85. There is no doubt that where a school believes in work experience and finds it possible to arrange, such experience can be a stimulus. Of an 11-16 comprehensive school, HMI remarks that the work experience scheme operates for fifth year pupils each year in June when CSE examinations are out of the way. Pupils spend one week at a firm of their own choice, and a second at another firm of a different type. Thus they are occupied for part of the time in gaining experience of work in which they have declared an interest. One boy who wanted to be an electrician wrote, after a week at an electrical contractors - 'The visit has been of great value to my career and future engagements. I have gained a clear impression of

[page 35]

what is required in the job.' Another boy who hopes to become a police cadet did clerical work in the education officer's office, and he afterwards wrote - 'This job, funnily enough, is not at all what I expected; in fact it never bored me at all. I enjoyed working every minute - a fantastic boost to my working experience.'

86. The co-operation of employees and the care and thought that, in conjunction with careers teachers and careers officers, they have put into the development of work experience, is impressive.

87. If there is value in giving pupils an opportunity to go out of school and see the world of work in progress, it is of equal if not greater importance for members of the careers staff themselves to establish contacts in industry, commerce and the professions. In schools as a whole, 12% record one teacher released for a short period to industry, and a further 6% record two or more teachers so released.* It must be remembered that a number of teachers enter the profession after experience, sometimes considerable, in other occupations. Many schools have yet to realise the potential value of releasing teachers, who have not had such experience, to industry for a short period.

88. Meanwhile, co-operation between schools and industry can be achieved in a number of ways. In one instance, a schools/industry liaison committee has been set up and, as a result of its activities, a day seminar has been held in which groups of managers and, later, groups of supervisory personnel have spent a day observing the life of the school and talking to members of staff and to pupils. At another school, a conference was held in the Autumn of 1972 at which local employers were invited to discuss the implications of the raising of the school leaving age. In a third case, the careers master is planning to spend a fortnight with a local firm as part of a programme designed to foster co-operation between school and industry. A number of schools visited have taken part in the C.B.I. scheme for introducing teachers to industry.

89. Careers conventions have for some years provided a means for informing young people and their parents about a variety of careers and occupations. For both schools and careers officers

*These percentages refer to all teachers and not specifically to careers teachers.

[page 36]

the organisation is a time-consuming business. The value of these occasions depends on the ability of industry, commerce and the professions to explain and illustrate the opportunities they offer. A careers convention appeals to many boys and girls when they are exploring possibilities for the future, but it is no substitute for a continuing process of careers education.

90. The impression made by visits to 84 schools (discounting those with an age range 11-14) is that seven have well established and profitable relationships with industry, commerce and the professions; that 13 recognise the value of such relationships and are attempting to foster them; that 29 maintain a bare adequacy of contact and that in the remainder, the task has yet to be faced. It seems clear that many schools in this country are not effectively in touch with the working world. Those schools which have already created relationships with outside agencies are reaping benefits for both teachers and pupils.

[page 37]

Boys and girls in special schools

91. Careers education is nowhere more important than in the special schools in which local education authorities and other agencies cater for severely handicapped children - the blind and partially sighted, the deaf and partially hearing, the physically handicapped, the delicate, the maladjusted, the educationally subnormal, the epileptic and those having speech defects. In January 1972, 146,390 children, excluding 826 children boarded in homes, were being educated in a special school or class, or they were awaiting admission. There were at this time 1,389 maintained special schools and 112 non-maintained, including 438 schools for mentally handicapped children for whom responsibility was assumed in 1971 as a result of the Education (Handicapped Children) Act, 1970. Approximately two thirds of all special schools contain pupils of secondary school age.*

92. Any description and assessment of careers education in a special school must take into account the special problems which it faces. Some children suffer a handicap which, if they are fortunate, will not deter them from entering employment in sheltered conditions or even in the open market. Some on the other hand may need to be cared for throughout their lives. A few are so afflicted that physical deterioration means that they have only a short time to live. Within any one school - and it may be very small - there are great differences between pupils in their physical condition, intellectual ability, achievement, emotional stability, social competence and family background. Disability may range from mild fits to

*For purposes of the survey, the questionnaire was sent to one special school in three in England, and two out of three in Wales, excluding the schools for which responsibility was assumed in 1971, excluding also schools with no children of secondary school age. Altogether, 281 special schools were sent questionnaires and these included 31 non-maintained schools. 25 schools in England and four in Wales were visited, and the schools chosen represented, as far as possible, each type of special school. Approximately 12% of the schools in the sample were in rural areas: 56% were urban and 31% in an urban/rural setting. Many of these schools are small; over one in four contains less than 50 pupils. This fact, coupled with the number of different types of school to be taken into consideration, made a comparatively large random sample necessary. Even so, the task of evaluation has been difficult, and firm assessments have been made only where evidence has proved convincing.

[page 38]

complete lack of control over both arms and legs. One handicap, moreover, very frequently implies another: a physical disability may be accompanied by severe behaviour problems and by educational backwardness. In addition, a handicap has direct and obvious results in limiting a child's ability to work with others on equal terms; it often has the less obvious but the sometimes more severe effect of determining how the child is treated by others. Many pupils, particularly the educationally sub-normal, come from less privileged homes, and contact both with home and with the Careers Service is made just that much more difficult to children in the schools which are in rural areas. Furthermore, the relatively small size of the school community makes it highly unlikely that a designated careers teacher, trained for the work, will be available. This contingency, coupled with the decrease in the limited range of occupations open to the handicapped, intensifies a problem already acute.

93. In special schools, careers education, viewed as a preparation for adult life, may mean simply teaching the educationally subnormal to read, to do everyday arithmetic and to work with others; and to make the young people realise that these skills and attitudes are essential to success in work or happiness in life. For the physically handicapped, careers education may mean building up self confidence, developing skills and enthusiasms that can make life worth while and employment a possibility.

94. About half of special schools have no designated careers teacher, and only 40% state that the careers teacher has received some form of in-service training in careers education or personal counselling. There is a striking contrast between the concern that many special school teachers show about the job prospects of their pupils and their own lack of training for careers work.

95. Careers education is a task largely shared among all members of staff of special schools. There is ample evidence of the care and devotion shown by heads and teachers; and if patience, sympathy, forbearance, encouragement, and common sense are attributes of careers education, then special schools do not lag behind in this respect. Nevertheless, there is much to be done and much expertise to be acquired.

96. Very few schools (7%) possess a careers room; 74% lack any storage space and 85% any filing equipment for careers education.

[page 39]

To expect space specifically designated for careers work would be unreasonable, but absence of storage space and filing equipment represents a serious deficiency.

97. Publications are usually available. They are openly displayed in about half of the special schools, readily accessible in 71%, available for borrowing in 63% but documented and catalogued only in 15%.

98. One observation is of particular relevance to special schools catering particularly for children who are educationally subnormal, and it has relevance, too, for any school which contains boys and girls with learning problems. Published material about careers is normally written for those who have no difficulties in either reading or comprehension. The deputy head of one special school visited has commented strongly on lack of suitable material for poor readers, and has expressed a wish that some publications may be produced in a simple, pictorial form. Some books which make use of pictures describe occupations which are and will be beyond the reach of young people with acute learning difficulties. Since the autumn of 1970, CYEE has published each year twenty titles in the If I Were series of occupational leaflets. These seem particularly useful since they contain direct, basic information written in simple language. In one local authority, two teachers have developed, over a period of some years, a way of integrating teaching about the world of work with knowledge of the various skills, attitudes and conditions in the area with which they are concerned. This has resulted in a series of booklets on various trades which is now published.

99. It is difficult also to cater effectively for blind and partially sighted children. Some pamphlets, the contents of which do not become too rapidly outdated, have been translated into braille, but these are difficult to produce and they are both expensive and bulky. Some publications have been recorded on tape, and a further development of the production and use of such recorded material is highly desirable; a cassette library would be a valuable asset for blind children. For pupils who are partially sighted, much helpful printed material on careers is available for those who can use either magnifiers, overhead projectors or other similar aids.*

*These matters and the whole problem of careers education for children with visual handicaps are discussed in detail in The Education of the Visually Handicapped - a report of a Committee of Enquiry. HMSO, 1972 (£1.07 by post).

[page 40]

100. For deaf and partially hearing, as for some slow learning children, the usual range of careers literature is often unsuitable because the language in which it is written is too difficult for them. One local education authority, realising the difficulties which some boys and girls find in understanding the language of official literature, has set up a working party to design simpler versions and to consider the production and supply of more suitable material to schools.

101. Television is used by 85% of special schools in connection with careers education; 2% use radio, 4% films and 1% film strips and slides. Some teachers complain that for many handicapped children the pace of some television programmes is too fast and their content too demanding.

102. For the special school contacts with the outside world obviously present severe difficulties. Nevertheless, the link with the careers officer should be strong and the relationship as close and continuing as it is in any other type of school. In 95% of special schools, the careers officer visits at least once a year; 71% are visited six times a year or less, and 7% twenty five times or more. The pattern of visiting varies considerably from school to school and from area to area. Clearly the effectiveness of the careers officer depends on the degree of involvement with members of staff and the pupils, as well as in planning careers programmes and talking to parents. In a third of special schools the careers officer helps to plan the careers programmes; in half of the schools to plan works visits; in 19% to plan work experience and in 26% to plan talks to parents. Contact with the head takes place regularly in 53% of schools and occasionally in 39%. Members of staff are met on an informal basis in 80% of schools, and at staff meetings in 8%. These findings compare unfavourably with those for other types of schools (see paragraph 60 et seq).

103. It is clear from statistical evidence that the careers officer cannot, in many cases, know the children well enough to give them effective help. In 44% of the special schools he or she meets them first when they are in their fifth year; in 43% of cases in the fourth year; in 10% of schools in the third year and in 5% during the second year. Although in two thirds of special schools the careers officer interviews leavers more than once, a closer working partnership

[page 41]

between special schools and the Careers Service seems clearly needed.

104. The evidence of visits to schools suggests, however, that personal relationships between the careers officers and schools are generally good. Several schools pay warm tribute to the careers officers. 'She is the king-pin as far as we are concerned', is the comment of one head. Of another careers officer it is said that 'he is a frequent visitor both for interviews and on such state occasions as "open day". In other words he is a familiar figure to all the older pupils and tries to meet many parents. He is sympathetic and on friendly terms with all the staff.'

105. Some visits suggest, on the other hand, that no sense of forward planning emerges from discussions between the school and the careers officer, and that too little attention is paid to developing an effective service. Difficulties can be caused if there are two separate careers officers attached to one school (for example, a man for the boys and a woman for the girls), or by the distance that specialist officers must cover to see all their schools. Of a boarding school, an HMI comments that since all the boys are resident and come from all parts of the County, many of them will return to their home area when they leave school. The school's careers officer must therefore keep in touch with careers officers in the areas from which the boys come. In another case the careers officer for this school is based miles away. She makes every effort to visit the school regularly and does so three to six times a year, though there are few leavers - only six this year. But because of pressure of work and her wide responsibilities in a county area, she is unable to give the school much help in planning its careers programme. Because of the distance of the school from their homes, parents rarely attend careers interviews. If they wish to do so, they have to bear all the costs of travel themselves.

106. Some development of the service provided appears essential if the pressing needs of handicapped children are to be met effectively. The fundamental principle is continuous guidance. The child changes and so does the situation outside. There must be sustained, systematic review. Too often, the careers officer sees the handicapped child too late and without opportunity for deeper investigation. In the opinion of one careers officer, 'to wait until

[page 42]

the final year often leaves inadequate time for guidance and for application to be made for appropriate training or assessment at a centre, or even for finding a suitable job. It is unfair on disabled youth to let them go out into the world without adequate support, and then wait to see how they cope, assisting them only when they have had a series of failures and setbacks that might have been avoided'.

107. Organised links with higher and further education are difficult to establish. Visits to and from such institutions can rarely be achieved. Some heads of special schools are nevertheless anxious to encourage linked courses specially devised to meet the particular needs of their pupils. In one authority, arrangements have already been made in a college to accept pupils of an ESN school in their last year for part-time training in motor and building trades. Girls have attended short courses in first-aid, physical education, home economics and in woodwork. In another area, there are special arrangements for children with hearing difficulties in a college of further education where a teacher from the school works part-time. The aim of such ventures is not to achieve examination successes, nor is vocational training the objective. The value lies in the ability to bring young people who are deaf into contact with normal students in the college of further education, and in letting them all work together. In individual cases, linked courses with local colleges have led to success in examinations.

108. Contacts with industry, commerce and the professions present similar difficulties. Speakers make annual or occasional visits to 43% of the schools, and visits to firms are made by all pupils in 54% of special schools (by some pupils in a further 36%). Sometimes these visits have little relevance to the future employment since the firms may be many miles from the pupil's home. Yet they may still have great social and educational value. Of a school for epileptic children, an HMI comments - 'To children in residential schools who have spent several years largely confined to a small and isolated community, it is important that they should see and be seen by people in more normal settings and also be stimulated by a change of scene.'

109. Work experience, arranged for all pupils in 8%, and for some pupils in 36% of schools, is designed more to build up their confidence than to involve them in the working world in any real

[page 43]

sense. It is sometimes a matter of boys spending time in the workshop and girls in the home economics room. In some cases buildings can be adapted for animal husbandry or as general workshops. Boys and girls are given jobs to do in a simulated work pattern with extended hours and shorter breaks. They learn to work without supervision. From one special school, boys and girls are employed as assistants for one day a week during their last year in school in the various departments of the local technical college. Each is attached to a particular person for a day: for example, to the boilerman, the caretaker, the groundsman, a kitchen helper or a cleaner. Pupils are expected to find their own way to the college, check in, make their own arrangements for lunch and to work a full day - usually from 8.30 am to 5 pm. An exceptional case is a purpose-built factory unit in a city on the south coast, which since 1967 has given work experience to certain leavers from a secondary ESN school. Pupils attend for 4½ days each week for an average of about 2½ terms, and they undertake a wide range of jobs for local factories. Attempts are made to give them experience in as many aspects of industrial life as possible. The aim is to prepare them for work generally and not for particular employment. By 1970, provisional results indicated that about half of the pupils who had attended were still in their first job after leaving the unit. A somewhat similar but shorter course is run in a Welsh county in an Industrial Rehabilitation Unit.

110. The philosophy of careers education in special schools tends to be based more on a concern with social development and acceptance than with preparation for work. Of one school it is said to be concerned not so much with preparation for a restrictive range of narrowly defined work situations as with producing a stable person, equipped with competence and basic skills and an acquaintance with normal working practice. In a school for maladjusted children, the main element in their education is rehabilitation to enable them to take their place in normal society and deal with the stress and pressures society places upon them. Preparation for life is the keynote. Of one school, HMI declares that all members of staff are involved in this work; indeed their main function is to engender in the children greater responsibility for themselves, greater emotional stability and the ability to live in the world and accept its pressures. Inevitably the range of occupations available is narrow, and part of the education must be preparation of

[text continues after graphics]

Plan A

Adapting space for careers work

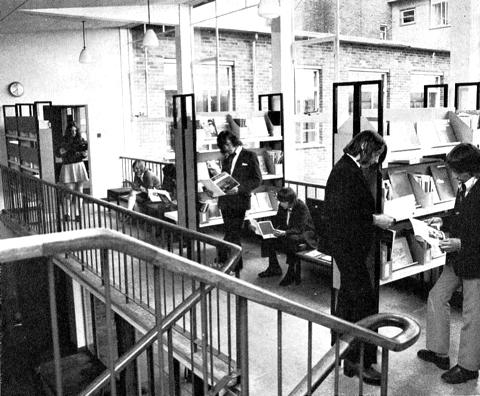

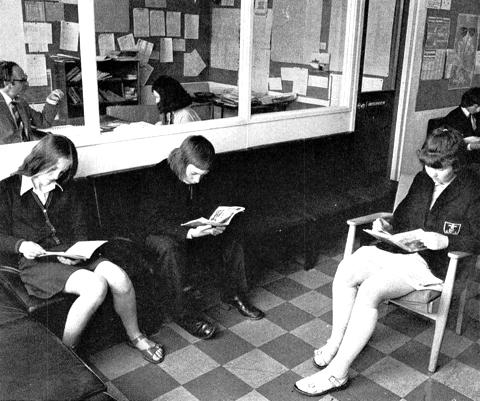

Plan A The gallery provides ready access for pupils freely to consult or browse through careers literature.

Plan A A separate office for the head of careers department.

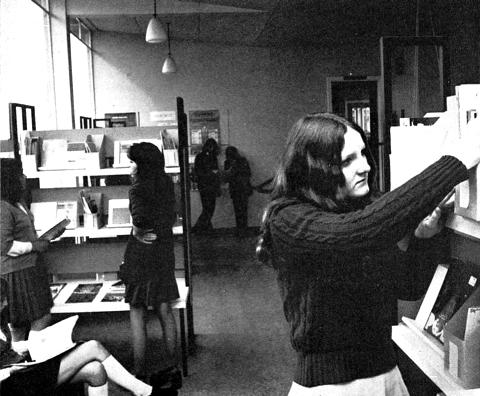

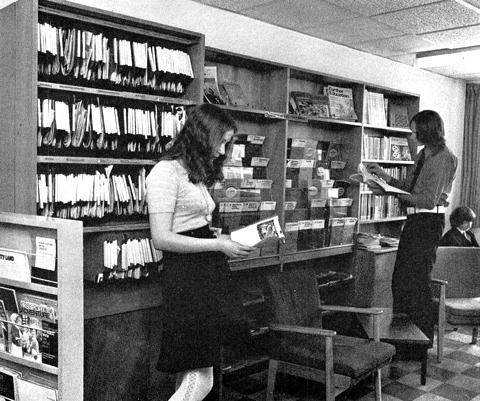

Plan B A careers library-cum-tutorial room is part of a purpose-built careers suite (see overleaf)

Plan B Attractive displays of literature, comfortable chairs and a welcoming atmosphere.

Plan B

A purpose-built careers suite

[page 44]

these pupils for this limitation. This means that careers education is seen as part and parcel of the total educational process which concentrates on social skills, numeracy and literacy with pupils up to the age of 15, followed by a special leavers' course.

111. Careers education is usually therefore a team effort and a matter of infusion rather than of timetabled time. Though about two thirds of schools devote some periods specifically to it, such periods are generally few in number, and in half of these schools they total less than the equivalent of two fifths of one teacher's work load. In many schools, periods devoted specifically to careers work are part of a special leavers' course.

112. For the physically handicapped who may be highly intelligent, preparation for life, apart from coming to terms with and compensating for some grave disability, is a matter of discovering, in individual cases, ways and means of developing talents that can be put to good use in the adult world. For the educationally subnormal it is a matter of concentrating on the development of personality throughout the whole of the secondary course. 'Self assurance, confidence and the ability to mix with other young adults', says one head, 'seem to be the essential qualities ESN leavers should have if they are to make a success of employment. These attributes are not achieved by industrial or vocational training alone though this may help, but rather as a result of all the activities experienced by pupils throughout their school careers ... but it would be quite wrong to imply that no special preparation for leaving school is necessary. Indeed the contrary is so. Especially during the last year of school, slow learners need to be prepared to meet the problems associated with leaving and to stand on their own feet. Form teachers responsible for the senior boys and senior girls will ensure that all relevant ground in the Environmental and Social Studies scheme is covered, in addition to a simple scheme for leavers.'

113. This particular school's leavers' course in Environmental and Social Studies is designed to make every boy and girl familiar with the world around them. It includes:

(i) Going to work - kinds of employment available; Employment Exchanges; forms to fill in; answering questions; interviews.

(ii) Travel - distances from work; fares, bus and rail transport; timetables; maps.

[page 45]

(iii) At work - duties; punctuality and good timekeeping; protection against accidents; conditions of work; trade unions; unemployment and what to do about it.

(iv) Money and work - earnings; piecework; time rate; overtime; bonus; deductions from pay; tax; pensions; National Insurance; private insurance; sickness; benefits; old age; budgeting; saving; hire purchase.

(v) Public life - rights and responsibilities of the citizen; law and order; visit to a magistrate's court; religion, race and colour; a visit to a post office.

(vi) Current affairs.

(vii) The family - responsibility and relationships; hygiene; illnesses; doctors and hospitals; the Citizens Advice Bureau.